Terry Ball – renowned shoe salesman, friend to former mafiosi – has vowed to spend his remaining years finding ways to cheat authorities he feels have cheated him. His greatest ruse? A tax-dodging snail empire

It is a drizzly October afternoon and I am sitting in a rural Lancashire pub drinking pints of Moretti with London’s leading snail farmer and a convicted member of the Naples mafia. We’re discussing the best way to stop a mollusc orgy.

The farmer, a 79-year-old former shoe salesman called Terry Ball who has made and lost multiple fortunes, has been cheerfully telling me in great detail for several hours about how he was inspired by former Conservative minister Michael Gove to use snails to cheat local councils out of tens of millions of pounds in taxes.

His method is simple. First, he sets up shell companies that breed snails in empty office blocks. Then he claims that the office block is legally, against all indications to the contrary, a farm, and therefore exempt from paying taxes. “They’re sexy things,” chuckles Ball in a broad Blackburn accent, describing the speed with which two snails can incestuously multiply into dozens of specimens if they’re left alone in a box for a few weeks. Snails love group sex and cannibalism, he warns.

As the conversation drifts away from snail breeding he describes personal connections to a very prominent member of the House of Commons, his years hiding Italian mafia killers while they were on the run, and the potential market for snail salami. Almost everything he tells me seems improbable, yet everything I could later verify checks out. I’ve got little reason to doubt the rest.

We’re drinking with “Joseph”, a snail farm employee. An hour earlier I’d seen him using a cleaver to chop up lettuce to feed thousands of the animals. They’re then shipped out to premises across the country, including four big snail farms they’re currently running in London. Taking out his phone, Ball shows off pictures of another man, “my mafia boss friend”, posing with the legendary Napoli footballer Diego Maradona in the 1980s.

Joseph, who speaks with an unusual Italian-Lancastrian accent, turns out to be a man called Giuseppe from Naples. In a very matter-of-fact manner, Giuseppe explains how he previously spent four years inside prison because a former friend, a convicted mafia murderer, turned into an informant and helped the Italian authorities convict his former criminal colleagues. Ball says he has employed Giuseppe to look after his tax-dodging snails as a thank you. Giuseppe once warned him not to travel to Italy, at a time when the snail magnate might have been prosecuted due to the confessions of the same informant.

Three hours earlier I knew none of this. I’d turned up unannounced at Ball’s snail farm HQ with a faint hope that I might catch a glimpse of the man behind one of the most brazen tax dodges I’d ever encountered.

Standing by the concrete snail statues that guard the security gate outside the snail farm, I’d expected to be told to piss off. Instead, I was met by Giuseppe, who phoned his boss. Seemingly intrigued by a journalist who had travelled 250 miles from London to stand in the rain without an appointment, I was told to come back an hour later for the first ever interview with Ball, a man whose photo had never even appeared online until now.

Over the ensuing hours, Ball makes confession after confession about his attempts to outwit the taxman with increasingly elaborate plans, his decades-long links to the Naples underworld, and how at this very moment there are buildings across London where he is deploying his unique snail-breeding method in a bid to cheat exasperated local councils out of millions of pounds. “I’m turning 80 next month and I haven’t got jack shit in my name. What are they going to do?” Ball tells me with a chuckle, when asked if he’s worried about prosecution. “You can’t take nothing off nothing. They’ve stopped torturing people.”

Ball is proudly committed to spending his remaining years on this earth finding innovative ways to get revenge on the “bastard” authorities who he feels screwed him over in the past: “I just do it for devilment. I do it just to get away with it.”

None of this, it is fair to say, is normal. But almost nothing about this story is.

Right now, if you take the tube to Edgware Road and walk a few minutes down Old Marylebone Road you’ll find Winchester House, a 1970s office block that is awaiting redevelopment. If you head up to the sixth floor and put your ear to the door, you just might hear the low-level hum of snails in boxes munching lettuce and breeding.

All of the snails inside the office block are living inside sacks branded with L’Escargotiere, the name of Ball’s snail farm. For Ball, these molluscs’ sole purpose in life is reproducing in order to enable tax avoidance.

The tenants of the various floors of the office block have names like Snai1 Primary Products (2023) Ltd. All of them are companies registered by Terry Ball for £35 a go. He is the sole director of each of them but tells me he has no intention of filing accounts for them and no plan to pay any taxes. They don’t take any income or hold any assets. They’re just shell companies created to sign the legal paperwork. Every so often a local council successfully has one liquidated for unpaid debts, so Ball just phoenixes it – abandoning the old company (and with it, its debts) and starting a new one. Westminster is now seeking to recover more than £286,000 from Ball’s companies, which it says are running multiple tax-avoiding snail farms in Winchester House.

Ball’s desk is covered in stacks of brown envelopes addressed to his various shell companies. I spot some featuring the logos of HMRC and Companies House, while others come from Westminster and Barnet councils. At one point the businessman proudly holds up a stack of paperwork relating to the Old Marylebone Road property to highlight how Westminster council appears to have accidentally approved some of the farms.

Most people understand the concept of council tax, which is paid by people living in houses and flats to their local authority. Business rates are the commercial equivalent, paid by the occupant of an office, shop, or other non-residential property. Under a rule change introduced by Gordon Brown in 2008, if a commercial building has no tenant then the landlord has to pay the property tax in full.

This means a landlord with an empty office or shop in a major city can quickly find themselves paying hundreds of thousands of pounds a year in business rates, despite having no income. One solution is for the landlord to let the office out to a legitimate tenant on the cheap. Another is for them to find someone who will accept a small fee in return for signing a lease and taking on legal responsibility for paying the taxes.

This could be an overseas student willing to claim they are running a gift shop who can amass a large tax bill before fleeing the country. Or it could be someone running a business that has a complete exemption from paying business rates, such as an agricultural enterprise. This category, Ball clocked while reading tax guidance at two o’clock one morning in the 2010s, includes fish farms.

The problem is that running a fish farm in a central London office block is very complicated. Breeding salmon is tricky as you’ve got nowhere to release them. You could breed crustaceans such as lobsters, but they need lots of love and attention to ensure they meet food hygiene laws.

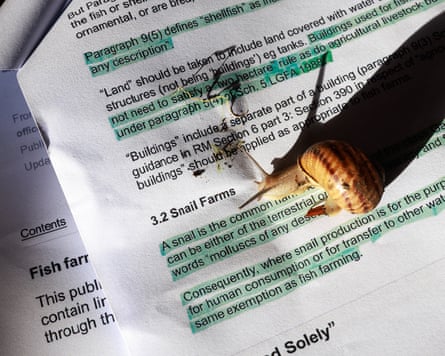

But in the small print of the HMRC guidance, Ball noticed that there was a further clarification regarding the law. In the late 1980s, a government minister told parliament that the legal definition of a fish farm includes a site breeding “molluscs of any description”, a rule designed to cover oysters. The minister confirmed that, as land-based snails are also molluscs, any business breeding snails for human food consumption is legally a fish farm – and potentially exempt from business rates.

L’Escargotiere HQ is located on the edge of the tiny picturesque village of Ribchester, an ancient settlement in the Ribble Valley between Preston and Blackburn. “It’s a very middle-class village,” says one resident. “It’s like something out of a Joanna Trollope novel.”

Inside a recently built corrugated metal shed is a giant freezer containing 6,000 snails in suspended animation, awaiting their deployment to another office block. The snail farm’s website says they will sell you 1kg of the animals for a mere £14, but it doesn’t look like there’s much direct-to-consumer trade. A caravan sits outside, alongside a bonfire, plus a number of holiday chalets being marketed for up to £200,000. The snail farm, partly approved on the basis it would be an educational tourist attraction, is the subject of a planning dispute with the local council.

Ball’s daughter invites me into the building and sits me down in his office. True to tax-avoiding form, the office has been subdivided into different units that are all supposedly run by different companies controlled by Ball. One door has a sign saying the company specialises in “the development of snail extract mucus, skin creams, and beauty products”. The whole block has cables dangling from the ceiling. Behind the big wooden desk is Ball’s large leather chair. The scene reminds me of the lawyer Saul Goodman’s office in Breaking Bad.

Ball walks in with a glint in his eye and begins talking. He barely stops for an hour while he tells me his life story. He is a man driven by a commitment to ruining the lives of tax collectors by exploiting loopholes. Whether the loopholes actually work is another matter.

In his telling, Ball was born into poverty in postwar Blackburn, sharing a bed with his siblings while his father, Tommy, ran a market stall selling cut-price shoes in the mill town. What started as a small enterprise became a chain of shops across the north-west of England that, as the BBC reported after Tommy’s death in 2008, “revolutionised the footwear business”. It was built around a discount model based on buying factory seconds, products rejected for minor blemishes. His shops attracted coach trips from across the north of England.

Terry left school at 14 and followed his father into the shoe business, eventually going into direct competition with him following a family feud. In the early 1970s, Terry began to travel to Italy to pick up discount shoes. He was, he claims as he holds up a dusty old leather shoe that sits on a shelf in his snail farm office, the only man to secure seconds from the late Giorgio Armani’s factories.

The problem, he claims, was getting the shoes back to the UK. Prior to the European Union he would lose shoes to corrupt officials at every border along the route. Then he encountered the Neapolitan mafia, who controlled the local port. Rather than drive a lorry across Europe, he discovered he could simply pay the local customs agent in Naples and have them shipped straight to the UK. Thus began a decades-long relationship with the Camorra, the dominant mafia organisation in Naples.

“I did them favours, they did me favours,” said Ball.

Terry Ball says that at various points he has been a multimillionaire. He owned big houses and property across the north-west of England. He experimented with different businesses, at one point distributing a beer called “Shag” and employing PR Max Clifford to concoct a successful media campaign to get it banned from Australia.

It was in the late 2000s, Ball explains, that he was radicalised on business rates, when a friend of his decided to liquidate a long-running family business. They wanted to do good by all their employees and pay their taxes, but were left during the financial crisis with an empty building they couldn’t sell that was running up tax debts to the local council. Michael Gove, Ball says, was the one man who had warned of this impact of Gordon Brown’s decision to impose business rates on empty buildings. “Why should you pay tax if there’s no income?” he asks. Ball waves around an annotated copy of a parliamentary speech by Gove, then a shadow planning minister, that he keeps on his desk.

Around this time Ball and his family were taken to court multiple times for attempting to evade taxes by repeatedly phoenixing companies and shuffling assets around different businesses. He was left defending himself and lost badly. Ball was declared bankrupt and banned from being a company director for nine years until 2016. This set him on a path to depriving the taxman through innovative methods: “I said you got £600,000 off me. I’m going to get £20m off you.”

In 2018 he began opening snail farm businesses in empty commercial premises on behalf of landlords, who paid his company 20% of the empty unit tax they were saving. This followed years of trials on how to keep them alive for extended periods of time. The snails, of which he bred Helix aspersa muller – the common garden snail – needed to stay alive for weeks at a time to meet the legal definition of a farm, but this was tricky. “The mortality rate is very high,” he says. “If you put more than two in a box you get cannibalism and you get snail orgies.”

Fresh food in the boxes went rotten, attracting flies and maggots. After three years of experimenting he says his breakthrough came with a trip to a local branch of Pets at Home, where he found hamster food that worked better. He worked out how to fatten up the snails, stick them into a freezer to hibernate, then drop them on to a site where they could breed and eat through their existing body fat for an extended period without the need for a human visit.

“I’m the ideas man,” Ball said, insisting he charges a modest fee to landlords for his attempts to reduce their tax bills. “We’re not robbers. We cover our costs. It’s the principle I don’t like.”

At first Ball sold his tax avoidance services under the brand name Crusader and told landlords he could cut the costs of empty property business rates by 93%. His PR was done by a man closely linked to Blackburn Rovers who signed up former Scotland football captain Colin Hendry to promote the company.

Business boomed. His daughter helped run it. Councils began raiding the snail farm premises and challenging the agricultural exemptions, leaving the landlords on the hook. A snail farm in Liverpool was raided. Earlier this year, Westminster council told the Sunday Times about one of the farms, a story Ball shared with friends on WhatsApp. In one notable 2021 court case in Leeds, a judge ruled conclusively that Ball’s snail farm was tax avoidance. Ball blames the very public Leeds setback on a landlord failing to abide by the strict guidance he sets out for his clients. (For his scheme to work, Ball says, it is essential that buildings are used solely as snail farms, and not for other purposes at any point.) In addition, some of his tax-avoiding landlords failed to pay his fees, a lack of respect which annoyed him.

Ball says he is now looking to diversify into a new “pop-up charity shop” business rates avoidance plan, exploiting a loophole in Charity Commission rules designed for tiny charities. A landlord will give him the keys to an office block and he will set up a “charity shop” and arrange for a small number of people to buy giant bags of mixed goods for a single day. The landlord will claim a substantial business rates discount on the basis it’s the premises for an unregistered charity. To enable this new tax dodge, he’s filled every corner of his snail farm with hundreds of thousands of pounds of cheap Chinese goods and toys. Ball insists I leave with a plastic crossbow for my child.

With Ball having happily confessed to enabling wide-scale tax avoidance through the medium of snails, the interview comes to an end. I’m shown the heliciculture centre a final time. Then things get substantially stranger. Ball begins talking with Giuseppe, fresh from chopping up snail food, about a former mutual acquaintance called Gennaro Panzuto.

Panzuto, the two men say while loading YouTube videos on their phones, is now building a career as an actor and influencer known as Genny Earthquake, who featured in a 2024 Ross Kemp documentary about the Italian mafia in Britain. But in his previous life Panzuto was a key member of the Camorra criminal organisation and was jailed in Italy for murder, mafia association, extortion, drug trafficking, arms trafficking and money laundering.

The two men laugh at Panzuto’s new existence as a TikTok influencer and anti-mafia campaigner. “I hid him for years,” Ball tells me, unprompted, pointing at the video of the convicted mafia killer.

Pardon?

“I HID HIM FOR YEARS,” Ball repeats, again pointing at the video. “Do you want a pint?”

A few years ago, the BBC’s home affairs correspondent Dominic Casciani interviewed an apparently repentant Panzuto inside a maximum security prison in Italy. The former “mafia kingpin” and senior member of the Piccirillo clan sat down and described his long life of crime on the streets of Naples and the murders he had committed.

Back in 2006, Panzuto realised the Italian authorities were on to him. He urgently needed to flee the country. According to the BBC’s account, one of Panzuto’s closest associates in Naples “had made deep connections to an organised crime gang in north-west England” involved in the sale of shoes. The gang was headed by a businessman “who appeared to be an entirely upstanding member of his community”.

Panzuto got in touch with the mysterious businessman, who offered him an escape and a new identity. When Panzuto arrived at Liverpool John Lennon airport, the businessman supposedly sent a Rolls-Royce to take him straight to a Lancashire pub for a pint of ale.

Panzuto told the BBC he was sometimes baffled by the indiscreet actions of the businessman, who paid to house him in a Lancashire caravan park and occasionally asked for debt enforcement activities in return.

While Italian crime was bloody and messy, Panzuto found that British crime was mundane and profitable. He was astonished to be shown how easy it was to commit tax evasion in the UK, concluding Britain had far less enforcement of financial regulation than his native Italy. Unlike the Camorra, his story went, his British host didn’t need to sell drugs, or extort money from local businesses. Instead, the British businessman simply shifted goods around from company to company, while dodging the taxes that other traders had to legitimately cough up.

The BBC did not name the businessman for legal reasons. But as we sit in the pub, Ball cheerily outs himself as the person in the story who paid to hide Gennaro Panzuto from the authorities. “I’ve known Gennaro’s family for a long time,” he says. “[Hiding him] cost me thousands.”

Sipping a pint of Guinness, Ball insists Panzuto overstated various aspects of the tale in the interview. The businessman disputes one detail of the BBC article in particular – he didn’t pick up Panzuto from the airport and he had absolutely not been driving a Rolls-Royce during that period. He’d sold it and had a Bentley by then. “What really happens and what gets in the papers is different,” says Ball. “They make it more flowery. I don’t blame them. That’s their job.”

This interview appears to be Ball’s opportunity to finally put his story on the record. Yes, Ball confirms, he did, for many years, offer Camorra gangsters an undercover getaway in rural Lancashire. His lawyer would fix them up with jobs in local restaurants, where they were loved for their willingness to work for free. By way of proof, Ball, who says he’s never sent an email in his life, sits in the pub looking up historic news reports on his phone about our drinking buddy (and his snail farm employee) Giuseppe’s past arrests for drug trafficking and involvement in the Panzuto case.

Ball insists he was never formally in business with the mafia but they did each other favours. When two factions of the same Naples crime family were at war in the mid-2000s, they asked Ball to mediate. He refused – so they had a summit at the local Lancashire caravan park instead. He says Panzuto’s uncles later personally apologised to Ball that their family member had “blabbed” to the authorities and given evidence. It clearly hurts Ball that he is no longer able to visit Naples. He’d once gone to watch Napoli, the local football club, where his mafia friends arranged for the club’s ultras to chant his name as a visiting dignitary.

Giuseppe, who said he served a lengthy jail term off the back of Panzuto’s evidence, recreates the chant in the pub: “TER-REE BALL! TER-REE BALL! TER-REE BALL!”

At the end of the BBC piece there is one final twist to Ball’s crime links. Anti-mafia prosecutor Michele Del Prete is quoted as saying he gave the UK authorities all the information he had about Panzuto’s British businessman host. “I remember the British told us that [the businessman] was definitely involved in scams – they’d known about this character,” the prosecutor told the broadcaster back in 2021. “But his links with the Neapolitan Camorra – that was news to them. We don’t know what they did with the information.”

The BBC said that Lancashire police did at one point open an investigation but that no one knew what happened to it.

In early October, a few days after my visit to Lancashire, enforcement officers from Westminster council accessed Winchester House, the office building on Old Marylebone Road, on the hunt for snails. What they found, according to photos shared with London Centric, was another of Ball’s operations.

Adam Hug, the leader of Westminster city council, told me he has repeatedly raised the “ludicrous notion of snail farms” claiming business rates exemptions with central government, but nothing happens. “Rather than unscrupulous traders dropping on one avoidance scheme after another, it would be good to see a general clause on business rates avoidance and evasion which stops these kinds of activities in their tracks. As a local authority with limited resources, we enforce wherever we can. We will be on the trail of the snail racketeers or anyone else who thinks they can cheat the taxpayer.”

The property’s landlord, a company based in the tax haven of the British Virgin Islands, is controlled by Iraqi businessman Namir El-Akabi, who made a fortune from contracts with western governments in the aftermath of the 2003 invasion of his home nation. He did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

In late November, Westminster council took one of Ball’s companies to the high court for unpaid taxes. The company was wound up in a hearing that lasted a couple of minutes. Ball didn’t bother to oppose it as he had no intention of paying the tax demand.

As Ball drove me back from the pub to Preston railway station in his Jaguar with personalised plates, he discussed what he wants to leave behind to his grandchildren, while simultaneously insisting he has no money in his name.

As we passed through local villages, Ball pointed out the various bits of land he’d bought and sold over the years. He also detailed his connections with high-ranking politicians, prominent businessmen, and showed messages he exchanged with a general in the Cambodian army.

I kept wondering why he was pushing on with his snail tax avoidance business, even though he was preparing to enter his ninth decade. Ball told me that fighting with the likes of Westminster council over tax helps stave off the boredom of old age: “All my friends who have retired, you can’t have a conversation with them, they’re just waiting to die. I’ve had a laugh. Every day, no matter what happens, I’ve had a laugh.”

This article originally appeared in London Centric, a new investigative news outlet reporting on the people and money that make London.

.png) 2 months ago

64

2 months ago

64