A hilly lane curves round Bunratty Castle. Through an open window, I hear a harpist plucking notes at a banquet drifting as the sun sets low over the battlements. On the other side of the lane, smoke drifts from Durty Nelly’s pub, where a singer is halfway through The Parting Glass. A short walk away, the limestone facade of the Creamery hints at its past lives – as a stagecoach stop, a dairy, a roadside inn. Tonight, it’s a pub.

Inside, Bríd O’Gorman plays the fluttering melody of The Cliffs of Moher on her flute, accompanied by Michael Landers on guitar – a quiet moment before the small crowd erupt into applause as Cian Lally pulls our pints. Just 10 minutes from Shannon airport, Bunratty village sits in the south-eastern corner of Ireland’s most musical county. Along the bar, visitors from the US and France lean in, quietly captivated – likely having their first experience of an Irish music session.

It’s no coincidence that County Clare is the centre of Ireland’s famous music scene. Clare is as close as any county comes to being an island. Hemmed in by the Atlantic on one side and the Shannon – the country’s longest and widest river – on the other, it was, for centuries, a place almost adrift from the mainland. Until the 18th century, when bridges finally tethered it fully to the rest of the country, Clare was reached mostly by boat or by traversing the Burren’s stony, unyielding landscape.

That isolation also shaped Clare’s culture. Beyond the reach of the capital, this corner of the west became a stronghold for language, music and tradition that flourished in the twilight on its own terms. You can feel that independence in villages along the coast, where the land abruptly falls into the sea at the Cliffs of Moher – or farther south, where Loop Head Peninsula stretches defiantly into the Atlantic, a windswept outpost that feels like the end of the world.

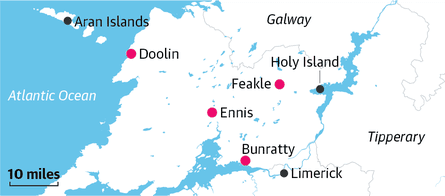

Yet even within Clare, there are really two stories, as distinct as the landscapes from which they emerge. Draw a line from Bunratty, through the county town of Ennis, all the way to the northern tip of the county, and you’ll see the divide. Locals speak not just of Clare, but of east Clare and west Clare – each with its own rhythm, character and musical soul.

I catch Bríd as she packs away her flute, and the audience turn back to their conversations and pints. She knows this music intimately. A native of east Clare, she is a firm believer that the soul of Irish traditional music doesn’t just echo through the well-trodden pubs of Gus O’Connor’s or McGann’s in west Clare’s Doolin; it pulses quietly and powerfully through the hills, lakes, and tucked-away venues of the east.

“East Clare music has a character all of its own,” she tells me. “It’s known for being slow, expressive, understated – soulful, even. You hear it, and you can almost feel the landscape it comes from. The gentleness of the hills, the stillness of the lakes of east Clare – it’s a stark contrast to the jagged landscapes of north and west Clare.”

The east Clare landscape may have a soft lilt, but its voice carries enormous weight. The monastic ruins on Holy Island (Inis Cealtra) – a round tower and churches – lie just off Mountshannon on Lough Derg, often shrouded in mist. It’s the final resting place of the great writer Edna O’Brien, a place where the sound of the breeze is carried through limestone walls with the same quiet dignity echoed in her prose. There’s something about this part of Clare that holds on to the lyrical, whether it’s in words or music. The land is lush and rolling, threaded with narrow roads and bright streams offering their own soft melody. At Quin Abbey, swallows call as they dart through the roofless cloisters, while in the pretty marina town of Killaloe, the cathedral bells mingle with the cry of gulls above the great lake. Like the land, the music isn’t loud or dramatic, but quiet, confident, waiting for you to tune in.

“People often look north-west when they think of music in Clare – Doolin, Ennistymon, Miltown Malbay,” says Bríd. “But east Clare is just as alive. You just need to know where to look.”

One such place is Feakle, a single-street hillside village lost in east Clare’s brilliant green landscape. It was once home to the famous herbalist and wise woman Biddy Early. However, it’s a 19th-century singer, Johnny Patterson, who is commemorated with a plaque in the village square. At a fork in the road on the village approach stands Pepper’s Bar, a distinctive yellow-and-green vernacular building that has served the community since 1810. Its compact main room features a homely fireplace, dance-worn flagstone floors and low-hanging beams.

On a Wednesday evening, the space fills with the pulse of jigs and reels performed on fiddle, bodhrán, tin whistle or accordion. The music is sometimes frenzied, hypnotic, even mesmerising: complex arrangements often delivered by some of the country’s finest players, including Martin Hayes, Liam O’Flynn, Matt Molloy, Sharon Shannon and Kevin Crawford. It’s in these east Clare villages, such as Feakle, Tulla or Scarriff, that you might realise you’re the only one in the room who doesn’t play, sing or dance.

On Thursday nights, Ger Shortt of Shortt’s Bar in the heart of Feakle picks up the guitar, joined by a full musical accompaniment. Meanwhile, it seems as if anyone not playing is likely taking part in the Siege of Ennis, a céilí dance performed with spirited energy.

Farther afield, Irish-language sessions are held at Gallagher’s in Kilkishen, while occasional music nights at Gleeson’s in Sixmilebridge also contribute to the rich musical tapestry of east Clare. Even the Honk Bar – hidden away on a bramble-filled lane near Shannon airport, not far from where Johnny Fean, one of the founding members of Celtic rock band Horslips, grew up – is known to host the occasional session. But eventually, all musical roads lead to Ennis.

“It’s the heartbeat of Clare’s music scene,” Bríd says. “There’s a session most nights at Ciarán’s, Knox’s, Cruises, the Diamond, the Poet’s Corner in the Old Ground, Nora Culligans. And don’t forget PJ Kelly’s – it’s a great spot too.”

Not every tune is played in a pub. “One of my favourite places to play is Glór in Ennis,” Bríd adds. “We run an open session there once a month – myself and Eoin O’Neill on bouzouki. It’s in the foyer, free to all, and open to musicians of every age and level. It’s spacious, welcoming and it’s been running for years. People love it.”

Ennis’s music scene is among the richest in Ireland, thanks to its deep pool of local talent, lively pub culture and a spirit that blurs the line between performer and audience. Mike Dennehy, owner of the red-and-black-fronted Knox’s Pub on winding Abbey Street, says: “Knox’s has a wealth of musicians of various styles from all over Clare playing daily. We’re known not just for the quality, but for our open sessions, with up to 20 musicians at once.”

The roll call of regulars reads like a Who’s Who of traditional music. Ennis is home to globally in-demand players such as uilleann piper Blackie O’Connell, accordionist Murty Ryan and banjoist Kieran Hehir. One of the scene’s crown jewels is Piping Heaven, Piping Hell, a weekly uilleann piping session hosted by Blackie O’Connell. “It started as an afternoon session,” says Mike, “and has become a weekly gathering of pipers from all over the world.” Held in Ciarán’s and Lucas’s pubs, it features a guest piper joining the regulars for an afternoon of music, laughter and storytelling.

Ennis also plays a key role on the festival circuit, hosting Fleadh Nua in May and the Ennis Trad Fest in November – events that have drawn legends such as Moving Hearts, Sharon Shannon, Andy Irvine and Lankum, and cemented the town’s status as a musical capital.

The west Clare scene is more relaxed, more immediate, the music blending with the conversation, and one tune flows easily into the next. Events such as the Russell festival in Doolin kick off the year in February, and by July, the Willie Clancy summer school transforms peaceful Miltown Malbay into a bustling, welcoming village of sound. It’s where my own daughter, Síofradh, honed her harp skills in a chaotic makeshift class.

That’s the thing about Clare. Whether it’s a gentle melody in Bunratty, a fireside session in east Clare or the lively pull of Doolin, the music – and the welcome – are always there.

Bunratty Manor has doubles from €119 and singles from €109, room-only. Clare Eco Lodge in Feakle has doubles from €90 and singles from €50, room-only

.png) 1 day ago

7

1 day ago

7