Who would have thought that Rhinoceros, written in the 1950s, would prove to be a stage-shaker today? Sometimes taken as a satire on the rise of the Nazis or the lack of resistance to East European authoritarianism, but surely more accurately described as a general attack on unreflecting conformism, Eugène Ionesco’s play is a hard thing to pull off. At least in Britain, where the expectation of naturalism runs deep. After all, the plot turns on the entire human population of a European village – bar one – turning into rhinoceroses.

There are touches of Kafka, without the black force. There are Beckettian gleams of despair without Beckett’s lyrical intensity – or brevity. Insisting on the one theme without ever quite making an argument, Rhinoceros can easily become both heavy-footed and elusive: a pachyderm peeping flirtatiously from behind a fan.

And yet. Here is Omar Elerian’s production, making the play seem weirdly true. Current parallels are not underlined but they are unmissable, in the conjuring of a galumphing horror and a miasmic atmosphere: contradictions need only be proclaimed for them to be evidently the case. Of course, even this is morally equivocal: after all, the theatre does dare the audience to believe the impossible.

On Ana Inés Jabares-Pita’s clinically white set, stage directions are read out – and disobeyed. The inert and the animate are merged. A woman takes her pet cat to the market. The part of the cat is performed by a water melon: first tucked, mewing, under its mistress’s arm; the great green fruit is later seen as the victim of a street accident, its red flesh gaping. Catherine Gibbons, head of wigs, hair and makeup, deserves an award: Hayley Carmichael’s barnet is an explosion – a wire-wool extravaganza. Joshua McGuire sports a strange jutting curl over his forehead, like – could it be? – the beginnings of a horn? Sophie Steer’s postwar victory-roll fringe is as solid as a sausage roll. Elon Musk in his cheesehead hat might pass unremarked.

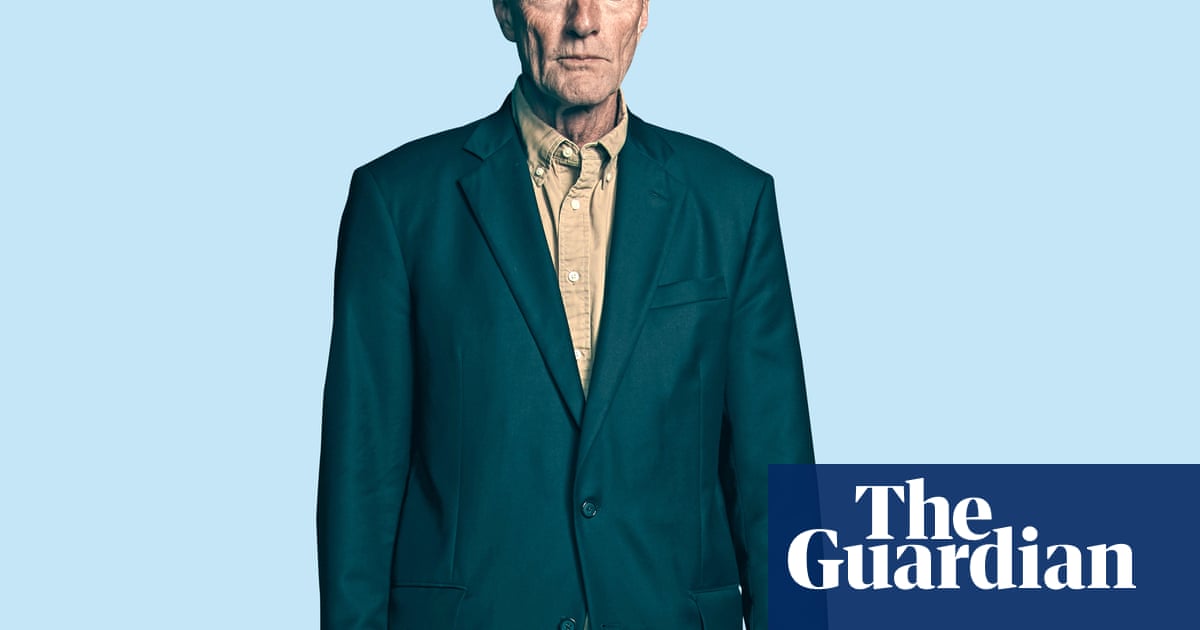

Paul Hunter (the narrator) and Carmichael move with the ease of their clown training: Carmichael seems to have no gap between feeling and gesture. , po-faced but intricate, is compelling, even when wrestling with a tight grey rhino suit. As the sole resister to the spread of rhinoceritis, Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù’s unvarying sincerity pays off in the closing moment.

There is another participant. Some audience members are issued with kazoos and instructed by Hunter when to blow, so that the theatre is filled with the trumpeting of rhinos, the baying of a bamboozled public. It could have been wince-making: it is apt. There is, though, no record of kazoos in the play’s first British performance at the Royal Court in 1960, when Orson Welles directed Laurence Olivier and Joan Plowright.

At pretty much the same time that Ionesco was throwing up his pen in despair at the lack of sense in European existence, Alfred Hitchcock was taking a sceptical look at life in the prospering United States. In 1955, mid-career, he embarked on Alfred Hitchcock Presents: 268 episodes of television chillers based on short stories. Jay Dyer (book) and the late Steven Lutvak (score) have made a musical out of slivers of these plots.

A frail old lady serves poisoned lemonade to the fellow who murdered her son. A man threatens to jump from a bridge in order to entrap and kill the cop who comes to rescue him. A housewife (no other word for her) bumps off her husband by hitting him over the head with a leg of lamb, then invites the policeman investigating the murder to eat the evidence.

These tales tilt one against each other with a similar murderous theme and droll outlook. The music is buoyant, with something of an Ink Spots swing, echoes of the Hitchcock signature tune, and the entire cast coming together to chorus “Everybody wants to kill someone”. Scarlett Strallen and Sally Ann Triplett almost burst out of their skins with vivacity and top notes.

The evening drifts sweetly, without suspense or propulsion. John Doyle directs with traces of the stripped-down style he deployed so memorably in his Sondheim productions 20 years ago. His cunning design is the best aspect of the show. Behind a proscenium arch in the shape of an early TV set (with bevelled edges), the cast caper around flimsy props: doors have no supporting walls, a ladder stands in for the suicide’s bridge. The stage is overhung by an outsize camera and an extra-long phallic mic. Monochrome dress is made for black-and-white telly: a spectacular New Look frock with heart-shaped patch pockets; a pair of snazzy check pedal-pushers. The pattern of a knitted pullover suggests the cross-hatching on a slightly blurred grainy screen. It’s a decorative pastiche of fictions that, as satires on conventional morality, merit something sharper. Not for the birds, but no frenzy.

Star ratings (out of five)

Rhinoceros ★★★★

Alfred Hitchcock Presents: The Musical ★★

.png) 2 months ago

37

2 months ago

37