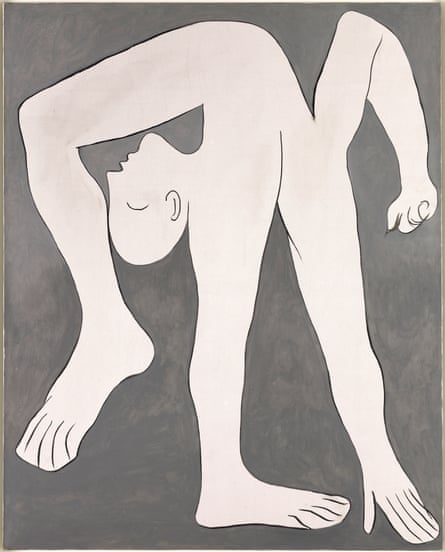

The Acrobat sums up the effect Pablo Picasso had on art in his 91 years on earth. In this 1930 painting, lent by the Musée Picasso in Paris, a body with no defined gender contorts into an insoluble puzzle, a leg sprouting above its anus, the head, eyes closed, bulging where genitals might be, the other leg standing on the ground balanced by an arm whose hand functions as a foot while the other arm, fist clenched, bends like a tail. In just this way, Picasso turned art inside out and upside down, twisted it unrecognisably, yet made it all the more compelling, human and passionate.

Born into a Europe of realistic sculptures and perspective pictures, he blew up those conventions, put them back together, then smashed them again, and a few times more. It’s hard not to be awed by his achievements, his turmoil of creative energy, the scale of his artistic breakthroughs, although Tate Modern tries its best. Theatre Picasso starts with coughing noises and references to gender and artistic borrowing. But those concerns go nowhere, vanishing in what becomes – almost despite itself – a riotous celebration of his genius.

It breaks Picasso up, as he broke up what he saw. There is no chronology or historical context. A piece of film shot by Man Ray of Picasso in a wig as Carmen – a holiday movie shot just after he’d painted Guernica – is followed by a selection of much later “obscene” images. In one of them, The Kiss, a man and woman give it a lot of tongue, practically eating each other, trying to get inside each another. In the same way, Picasso’s art wants to swallow the entire physical world. You can feel the fleshy wetness in your own mouth. He rejects realism to make you taste the real.

An artist who makes kissing look as filthy as this is hardly going to hold back when it comes to the nude. His 1968 painting Nude Woman with Necklace gets a spotlit wall to itself and a wall text drawing attention to his possessive depictions of women. As if we needed telling. In this blue-green tinted painting, we can see the model’s vulva and anus simultaneously as she fingers the necklace against her breasts. The critique misfires. Picasso was in his late 80s when he painted this, its rawness and anger as much to do with death as with sex. There is a pathos in his determination to go one better than Dylan Thomas and rage, rage against the dying of desire.

Death raises its hollow-eyed head insistently from this point in the exhibition. Picasso’s 1952 painting Goat’s Skull, Bottle and Candle is a memento mori that makes you glad to be alive. It’s a painting with the sharp lines of a drawing. The canvas is broken up into white, grey and black disharmonious lozenges, the skull delineated in harsh sections with crystalline force to make you see and feel what he saw on the table in front of him, fresh from the butcher, starting to attract flies.

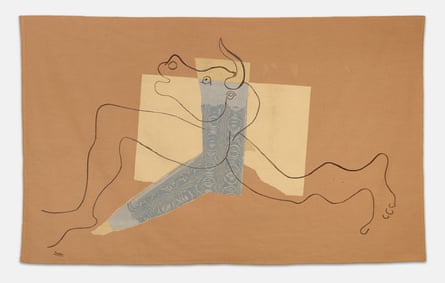

Death comes in the afternoon in a nearby 1960 drawing, in wet flowing black ink, of a corrida, a bullfight. A man on a horse has stuck his lance into the mighty bull that lowers its head as if in a willing self-sacrifice. Theatre Picasso claims to view the artist as “performative”, setting his works in a dark stage-like space, on theatre flats, with spotlights and mood music. The gimmick’s real effect is to illumine his Spanishness. (Cue castanets.) From his unlikely drag act as Carmen to this heartbreaking bullfight scene, the country he left as a young artist haunts the show just as its suffering haunted him.

In his 1937 comic strip The Dream and Lie of Franco, the fascist leader in the Spanish civil war is a genuinely obscene Don Quixote, his eyes on phallic stalks protruding from a hairy pig’s arse of a face as he squares up to a mighty bull representing the Spanish workers. As his violence becomes crueller, a woman flees a burning house with her dead baby in her arms, a timeless, devastating image of war.

Close by is Tate’s Weeping Woman, the great painting he did in 1937 alongside Guernica. You can see the Luftwaffe bombers reflected in her eyes. What you notice in front of the original here is how he added a stroke of blue over one plane, just in case it was too strident. So Picasso, tough guy artist, comes courageously close to bathos in this painting. As this woman weeps, her hair is a flowing river of hope while a bee feasts on her tears. Some good must come of the horror.

after newsletter promotion

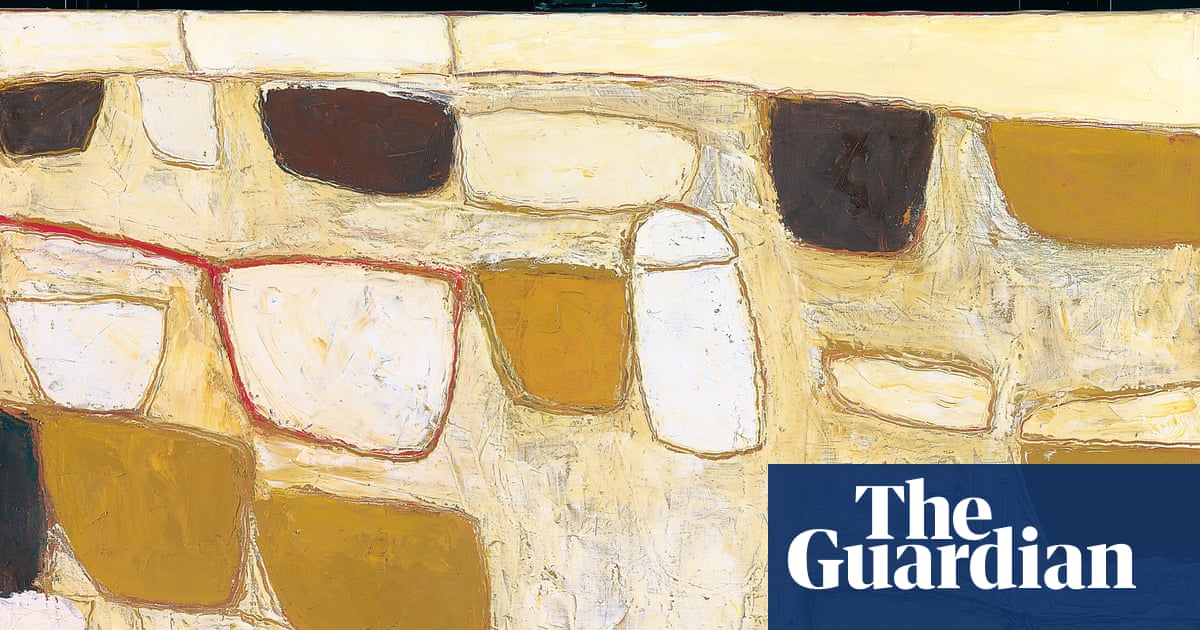

Picasso is a far more hopeful artist than such postwar figurative painters as Bacon, Freud or Auerbach. Is he even figurative? He is the inventor (with Braque) of abstraction and collage. In his early cubist art, there is no sex or death – just an eye engrossed by the small stuff of reality in which it sees infinities. You are brought back to basics by the dots of grapes in Bowl of Fruit, Violin and Bottle from 1913. So much beauty, so much mystery. It is because Picasso loves the little good things so much that he can face modernity’s horrors without despair. Welcome to his theatre of life.

-

Theatre Picasso is at Tate Modern, London, 17 September to 12 April

.png) 1 month ago

40

1 month ago

40