“There is a gap or a space where Alex should be,” Stacie Davies said. “Wherever I am, she’s not there.”

At just 25 years old, her daughter, Alex Davies, was found dead in her segregation cell at Styal prison in Cheshire on Christmas Eve last year.

She had been sent to prison after pleading guilty to offences including criminal damage and possession of a knife, which she had committed while in mental health crisis.

The expectation was that when Alex was sentenced, she would receive a hospital order, and four separate psychiatrists had recommended that she be transferred to hospital before sentence. Had the move been completed within the recommended 28 days, she would have left Styal by 23 December.

Alex had been diagnosed with severe borderline personality disorder and post-traumatic stress disorder from sexual abuse, and had struggled with her mental health for most of her life.

As a young child, she had been outgoing and confident, but at the age of about three, she disclosed she had been sexually abused. Stacie said: “From that day, for the rest of Alex’s life, she was very unwell.”

Despite her struggles in life, Alex was kind, generous, and funny. She was close to her four siblings, and so well loved in her Liverpool home town that at her funeral, Stacie said: “We had to open the back doors to let everyone in, 13 cars followed the hearse, I was overwhelmed, I couldn’t believe it.”

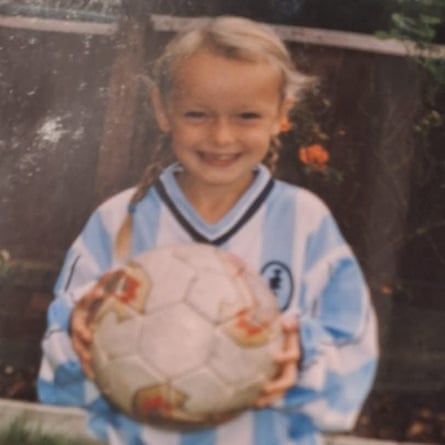

Growing up, Alex was also an incredibly talented footballer, who might even have had a professional career. “We recognised that she could play football,” her father, Alan Gerrard, said.

“So we got her into a team called the Fillies, and it was the best thing she ever did. She found a place, she found something she was good at.

“She was the best left back I’ve ever seen for a girl, Little Bainsey I used to call her,” after former Everton player Leighton Baines.

“She won everything you could ever win, teams like Man City, Everton, were all looking at her,” he added. However, “as she got a bit older, her mental health deteriorated.”

“She started to then misbehave in the football and in the end, it came to a place where she said, I don’t want to do it any more, Dad.”

As she entered her teens, Alex began self-medicating with cannabis and continued to struggle with the trauma of the sexual abuse, and the fact that the perpetrator had “got away with it”.

“Then she’d be very nasty with us,” Stacie said. “She’d smash the house up, and then she was becoming a risk to the other children.”

Alex spent time in care, “but this, for Alex, was rejection, abandonment, and she didn’t take it well”, Stacie said.

“She just went right off the rails. She was getting sexually assaulted and it just escalated really badly.”

From the age of 14, Alex was in and out of mental health hospitals, and she had been prescribed the antipsychotic clozapine, but she was titrated off the drug in May last year, after an abnormal ECG.

Although she initially coped well without the medication, her mental health rapidly deteriorated after she reported a sexual assault in August, and she was arrested in October after threatening her psychiatrist and possessing a knife.

Alex was sent to Styal prison, where she was kept on the care and separation unit (CSU) – a form of segregation – for 27 days. Alex had a history of suicide attempts and self-harming, and national guidelines state that prisoners who are at risk of suicide should not be kept in CSU unless there are exceptional circumstances.

At the 11-day inquest into Alex’s death at Cheshire coroner’s court in Warrington, the jury heard that Alex had been discharged from the integrated mental health team’s (IMHT) caseload after an assault on staff. Concerns were raised about some of the interactions team members had had with Alex, including one nurse telling her she would not be getting medication for depression and epilepsy “until she behaves”.

The jury heard that on Christmas Eve, Alex had been on her way back to her cell when she looked through the windows of the gym, and a prison officer told her to “stop perving”.

Alex became upset, ran off and was forcibly restrained before being taken to the CSU, the inquest heard. Footage shown to the jury of Alex being restrained and taken to the unit showed her repeatedly telling officers, “she called me a perv”. She screamed “I don’t want to go to this hell cell” and begged staff not to take her there over Christmas.

About five minutes after the cell door was closed, Alex began to self-harm. Items of clothing and bedding were removed from her cell until she was left wearing nothing but a pair of boxer shorts, while under observation by male prison officers.

“It’s worse that they knew that one of her main triggers was men, and men have stripped my little girl, and looking through her window,” Gerrard said.

And despite her persistent attempts at ligature and self-harm, Alex was not put on constant watch. The inquest found that neglect had contributed to her death – an extremely rare conclusion which can only be used where there has been a gross failure to provide basic medical attention and this has caused a person’s death.

“For a human being to die in a 21st-century prison from neglect is disgusting,” Gerrard said. “Something has got to be done now, because there are too many young girls and men dying through mistreatment.”

“It’s not about blame,” Stacie said, but the family want those who failed Alex to be held accountable for her death in the hope that it may stop others like her from dying.

Alex’s death, Stacie said, has left her family broken. “I don’t think I’ll ever be right again,” she said. “I’m not well, I can’t get right. I want to, for the four kids I’ve got, but I can’t.”

“It’s just doesn’t feel real, still,” she added. “I don’t even know if it’s hit me properly yet.

“Christmas Eve, I’m really going to struggle,” she said. “The strength will come, but the guilt as well, because she’s not here and I wasn’t there to protect her last year.”

The family was represented by Ciara Bartlam from Garden Court North Chambers inquests and public inquiries team, instructed by Nicola Miller, a specialist civil liberties solicitor from Broudie Jackson Canter.

“Alex should never have been sent to the wholly inappropriate surroundings of a prison where she was wrongly placed in effective solitary confinement, as they didn’t know what else to do with her or how to deal with her needs,” Miller said.

“HMP Styal is a women’s prison with a high number of self-inflicted deaths in comparison to the female prison population. Significant changes need to be made to ensure the women are getting the help and support they need, and lessons must be learned to prevent more young lives being lost.”

“This is a deeply upsetting and harrowing case – and it is clear the care Alex received on the day of her death while at HMP/YOI Styal fell far short of basic decency and respect,” a Prison Service spokesperson said.

“While it’s right we wait on the outcome of investigations, we would like to offer our deepest sympathies and ongoing thoughts to her loved ones.

“The prison undertook a number of immediate actions following Alex’s death, and we stand ready to put in place the prisons and probation ombudsman’s recommendations when they report back in the coming days.”

A Mersey Care NHS foundation trust spokesperson said: “Although we are unable to comment on individual patients because of rules covering patient confidentiality, Mersey Care routinely reflects on all our practices, but particularly after a tragic incident like this. We will continue to monitor our standards of care throughout our services and as a trust we remain committed to the delivery of high quality care for all our patients, services users, carers and their families.”

.png) 3 months ago

57

3 months ago

57