The first bluebells are out along the Dart gorge, creating a faint purple haze under the twisted oak trees. I’m on my way to Luckey Tor, one of Dartmoor’s most hidden rock stacks, which sits by the river, shrouded in vegetation like Sleeping Beauty’s castle. It’s not the easiest of walks. The path peters out as I get deeper into the gorge, and the final approach to the tor involves clambering and hopping over large mossy boulders and navigating huge shelves of rock that border the river.

The first sight of it is unforgettable. A small stream, the Row Brook, runs in front of it, like a moat. The tor looms up squarely from the valley floor, dwarfing everything around, framed in a grassy clearing that is a popular place to bivouac. Its position is unusual. Most tors are at the summit of a hill, dominating the views for miles around, standing grandly in the landscape, devoid of trees. Luckey Tor is sequestered in the folds of the Dart valley, and in the summer is mostly obscured by foliage; when you find it, you feel as though you’ve entered a secret kingdom.

The tor is one of hundreds on Dartmoor (the actual number is disputed). The name comes from the Celtic word twr meaning tower; it refers to a rocky outcrop that rises sharply from the land around it. These natural monoliths are about 280 million years old; they erupt from the moor, like stone beings, in a variety of outlandish shapes and sizes, looking like castles, creatures, monsters and giants. Their unusual appearance has given rise to numerous myths and legends: Vixen tor is home to Vixiana the witch; the devil resides at the Dewerstone (and numerous other places, of course); and Old Crockern, “the gert old spirit of the moor”, lives by Crockern Tor.

The authors of the first guides to Dartmoor called the tors rock idols because they believed they were worshipped by the druids. In 1793’s Historical Views of Devonshire, Richard Polwhele wrote: “In the druid ages, stones of various shapes were consecrated to religion … They prostrated themselves before the rudest … And wherever we find stones, which are at the same time massy and misshapen, there we look for the druidical gods. Vastness, in short, and rudeness were the characteristics of the druid rock-idols … ”

The idea of worshipping rocks is not exclusive to Dartmoor. Cultures around the world, including the Sami people and indigenous Australians, revere rocks; they are full of natural majesty and tend to be in high places, perhaps connecting us to the heavens and even the underworld. It seems likely that our ancestors on Dartmoor, who were more attuned to the landscape features than we are today, regarded the tors as sacred. And we know, from the monuments they left behind – notably stone circles and stone rows, of which Dartmoor has some of the best examples in western Europe – that they practised some sort of faith.

There is no doubt that Dartmoor feels like a sacred landscape, and its majestic rock stacks are part of that. They, and the moorland in which they sit, have been part of my life for the last 25 years; we first moved here back in 2000. I have walked among them, my children have played among them, and they have borne witness to many of the big moments in my life, both joyful and traumatic.

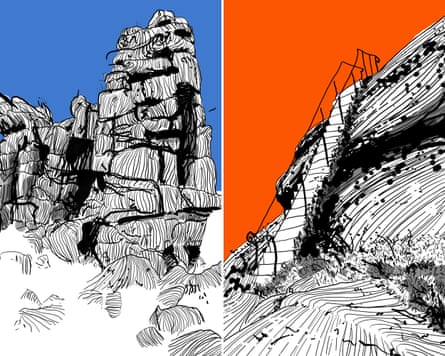

I first had the idea for an illustrated book about this place I love so much when visiting the Lake District. We used the hand-drawn Wainwright guides, which we found compelling because of their subjective, intimate feel; they really reflected Alfred Wainwright’s deeply personal relationship with the fells. I thought it would be great to produce a book like this for Dartmoor – with drawings by my husband, Alex, an artist. We ended up going on a granite pilgrimage, choosing 28 of the tors, and having wildly different experiences at all of them. They all have distinctive characters: Blackingstone Rock, with its surreal metal staircase going up the side, with curlicued, wrought-iron handrails, is a Victorian stairway to heaven. Hen Tor, by contrast, stands in total isolation, miles from anywhere, in an ocean of rock, like a stumpy cargo ship sailing forth in granite seas. And Watern Tor is an extraordinary ice-carved masterpiece of whirlpool granite, standing high above the Scorhill stone circle in the basin below.

Our passion for this place has resulted in us setting up a new festival too, the Dartmoor Tors festival (which runs from 23 to 25 May), to share the enchantment of the moor, and ponder why it makes us feel the way we do. We’ve got artists, writers, campaigners, archaeologists and musicians coming together to explore our human, emotional connection with wild landscapes. There will be talks and conversations, as well as a variety of walks, with artists, archaeologists and storytellers, to sacred sites including stone rows, cairn circles and, of course, the tors.

For us, the answer to why we love this place always seems to go back to the stone, the stone that connects us to our ancestors, that stone that they most probably worshipped, and which added a spiritual element to their lives. Paradoxically, stone is traditionally perceived as static and still, almost dead. But it is most definitely alive, just on a totally different timescale from us, existing in deep time, across millions of years, in contrast to our small, fleeting, lives.

Sophie Pierce, with Alex Murdin, is the author of Rock Idols: A Guide to Dartmoor in 28 Tors (Wild Things Publishing, £14.99). To support the Guardian order your copy from guardianbookshop.com. The inaugural Dartmoor Tors festival, runs from 23-25 May 2025

.png) 8 hours ago

4

8 hours ago

4