Julia Cárcamo López’s house faces the sea, near enough to hear the gulls calling through the salt-encrusted windows. She lives in the small town of Maullín, on the edge of Chile’s Patagonia, an area where almost everyone works in the fishing industry.

Outside, it is drizzling and the sky is darkening as she recalls 1 May 2019, one of the worst days of her life. “Two men knocked on my door and told me they had bad news: my husband had had an accident while working at sea,” she says. Since then, she has discovered that the accident seems to have been caused by negligence.

An autopsy proved that Arturo Vera, 59, a diver at one of Chile’s salmon farms, was struck by a boat’s propeller and injured in the head, ribs and throat. He had been working at the Taraba fish farm in Puerto Natales, in Magallanes, the southernmost region of Chilean Patagonia. Divers working in the salmon farm say the fatal injuries happened in violation of safety regulations, at a time when the boat’s engine was supposed to be turned off. The family claims to have received compensation in court.

Following Vera’s death, the company was fined for violations of labour and safety regulations identified by the labour inspector. The company was approached but did not respond to requests for comment.

Chile’s fast-growing salmon industry has been tied to deadly labour conditions, rampant antibiotic use and severe environmental damage, putting workers and communities at risk. Indigenous groups and small-scale fishers report polluted waters, vanishing wildlife and threats to their cultural practices.

“Over the last 12 years, the salmon industry in Chile has had the highest rate of accidents and deaths at work in the aquaculture sector globally,” says Juan Carlos Cardenas, director of Ecoceanos, a conservationist NGO. “Between March 2013 and July 2025, 83 workers died in accidents in the sector.”

Meanwhile, Norway has reported only three worker deaths in the salmon industry over the last 34 years, according to Ecoceanos.

“Those who eat Chilean salmon cannot imagine how much human blood it carries with it,” says one source working on a farm in Chilean Patagonia.

Salmon is not native to Chile’s waters. The first specimens were imported from Norway more than 40 years ago during the dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet.

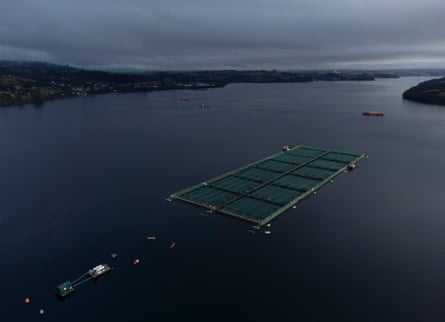

Chile’s salmon farms, or salmoneras, are the world’s second-largest producer of salmon after Norway, and fish is one of the country’s biggest exports. Between 1990 and 2017, the industry increased production by almost 3,000%, with more than 750,000 tonnes exported to more than 80 countries.

Chile is the leading supplier of salmon to the US, exporting 56,474 tonnes of the fish worth US$760m (£575m) in the first quarter of 2025 alone.

According to data from the Chilean government, from 2003 to 2024, imports of Chilean salmon into Europe grew from $56m to $204m, and the EU is now the sixth-largest market for Chilean salmon imports.

Yet the industry’s expansion has been at least partly driven by poor production practices that pose risks to human safety and the environment. A widespread use of chemicals and antibiotics pollutes water, destroying ecosystems and threatening other marine species.

While in 2024, Norway declared that it had used virtually no antibiotics in its farms, Chilean farms used more than 351 tonnes. This figure represents an improvement over 2014, when 563 tonnes were used, but it remains very high, given that studies suggest 70% to 80% of the antibiotics administered to salmon can end up in the environment.

Eating animals that have been treated with antibiotics can lead to antimicrobial resistance, and could promote the transfer of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to humans.

Small-scale fishers say they can no longer survive on fishing because many species, including sea urchins and mussels, are scarce due to pollution from the salmoneras.

Jorge Ampuero González, head of the provincial Labour Inspectorate in Puerto Natales, says he does not have the personnel or equipment to inspect farms that can take up to 12 hours to reach by sea. His team of seven oversees 30 salmon farms but has no boats or helicopters.

“Realistically, we can visit each centre once a year, at most twice. However much we want to, it is really difficult to change things with these tools,” says Ampuero González, who believes the industry needs improvement. “There is a lack of understanding that the sustainability of the industry does not depend only on how much salmon we produce, but on the conditions in which we produce it.”

The Chilean minister for the environment, the undersecretary for fisheries, the director of Chile’s national fisheries and aquaculture service (Sernapesca), the director of Salmonchile, the leading trade association of Chilean salmon producers, and the companies involved were approached for comment.

Pollution affects not just the Patagonian Sea, where salmon are raised, but also the freshwater stages of fish farming. The initial phase, including fertilisation and egg hatching, occurs mainly in Chile’s rivers in Araucanía and Los Ríos. A notable case alleging contamination involves the Chesque Alto community in Araucanía, which has been engaged in a lengthy legal fight against a local salmon company.

Near the polluted Chesque River stands a small wooden house where Angelica Urrutia, 35, and her family live. In a separate case, her community, the Mapuche – the largest Indigenous group in Chile – has taken legal action against the Sociedad Comercial Agrícola y Forestal Nalcahue (Nalcahue Agricultural and Forestry Commercial Society Ltd), which farms salmon in the area.

“Since the company set up shop,” says Urrutia, “the fish in the river have disappeared, as has the rest of the wildlife, especially the birds. When they were forced to stop in 2021 because of our complaint, the fish and other animals returned.”

According to community members, some parts of the Chesque River have turned reddish and slimy due to pollution, a phenomenon also observed in other areas of Chile where salmon farms have been set up near rivers.

“In 2005, four of our cows drank water near the company’s drain and all died. The vet who examined them said they had ingested a lot of formalin,” says Urrutia, referring to an allegedly carcinogenic chemical frequently used in salmon farming in Chile to eliminate parasites.

Urrutia says representatives of a salmon farming company came to their home and offered to buy them some sheep. “They do this so they can continue to work in peace,” says Urrutia. “Many of our neighbours are in favour of the company setting up here precisely because of these ‘incentives’.”

Yet, many residents are concerned about their health because they drink river water and use it daily in their homes. The salmon company was established in the area almost 30 years ago, in 1998, and, thanks to the legal battle fought by the Urrutia community in 2021, its activities had to be halted for about eight months. The company now faces an administrative sanctioning procedure, but continues to operate while it is ongoing.

Urrutia, who is a “machi”, an ancestral figure who is a pillar of support for the Indigenous groups in the area, treating its members with medicinal herbs and rituals, says there are other aspects of her people’s lives that are affected by salmon companies.

“I can no longer gather the medicinal herbs that grow around the river,” she says. “And the company has contaminated several areas of the river that my community has always used for our ancestral ceremonies. When the company had to stop, we were able to perform our sacred ceremonies in the river again. It was beautiful.”

-

Journalismfund Europe supported this story.

.png) 2 months ago

62

2 months ago

62