It is, scarily, 20 years since Bruce Parry first brought Tribe to the BBC. The diffident but determined former Royal Marine visited Indigenous people in the world’s most remote places and, by living as one of them, earned a level of trust that previous documentary-makers had struggled to achieve. Parry was more patient, more respectful and more physically courageous than other white interlopers had been. He gained valuable insights into tribal life and the threats to it posed by modernity. Tribe itself was simply cracking entertainment, as involving as it was educational.

Television’s sausage machine has a way of turning the most exotic ingredients into familiar comfort food and, although it took us to the farthest corners of the planet, Tribe soon established a reliable format. Parry’s return follows the winning formula as he travels to meet the 600-strong Waimaha people, deep in the Colombian Amazon rainforest.

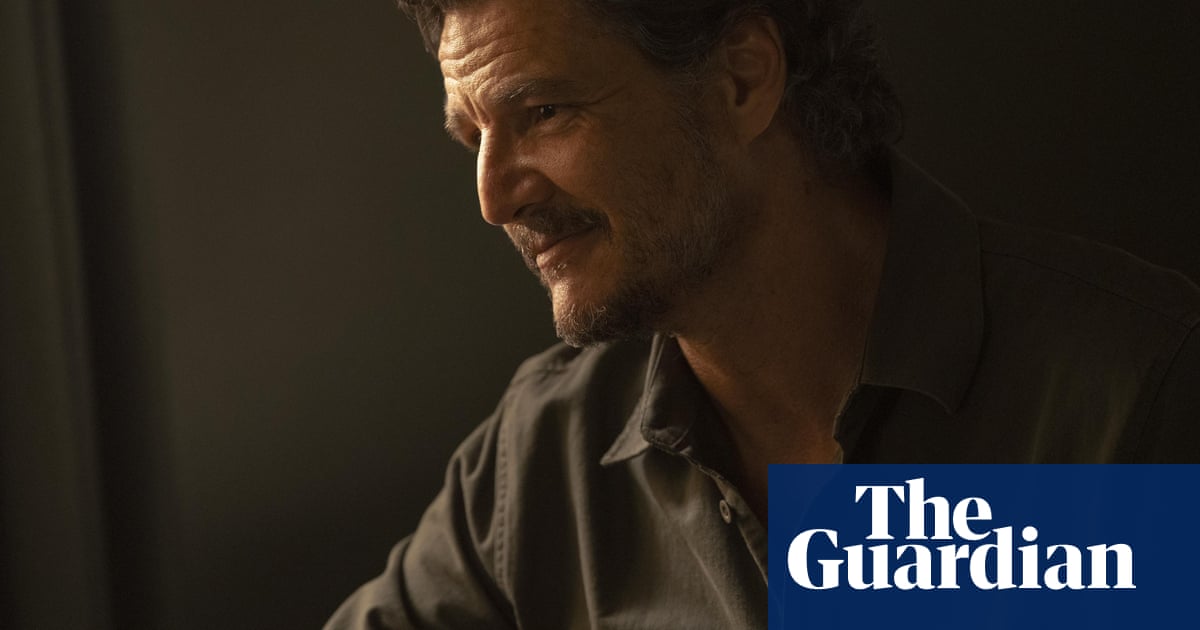

First, there is the journey in, via small plane and tiny boat, the camera snagging on a branch as the canoe weaves through foliage. Then it is the tentative first meeting with the village elder, a friendly man named Pedro who is nevertheless upfront about why Parry is getting funny looks: “We don’t think much of the white man. When we see you it brings back memories.” The Waimaha have been here for 2,000 years, having been brought upriver, legend has it, in the belly of an anaconda; a century ago they were massacred by invading rubber tappers, and as recently as the 1970s their children were forcibly taken and re-educated by Catholic missionaries.

Soon, though, Parry is ensconced with a family and winning favour by showcasing his wood-chopping skills on a trip out to find protein. He joins them in feasting on mojojoy, the fat white larvae of the palm weevil, which are eaten raw and, indeed, alive. “It’s got a lot of flavour!” says Parry, politely. “It’s like a custard that … isn’t that sweet.” Later on, Pedro, who is the local physician, finds a plant with medicinal qualities. He picks a lush leaf, squeezes it into a ball and dispenses a drop of green juice into each of Parry’s eyes. “Yeah, that … stings,” says Parry, fighting to maintain his gratitude. Pedro says this is a sign there is something wrong with his eyes.

Before long, Parry’s willingness to help with any domestic task has endeared him to the womenfolk, and he is making progress with the training he has to undergo before he will be allowed to join the villagers at a ceremony for the forest spirits, fuelled by the hallucinogenic plant extract yage, AKA ayahuasca. His sinuses are cleared by snorting ground chilli; his stomach is purged by drinking emetic leaf-water, a process that ends with him neck-deep in a river in the middle of the night, manfully hurling up gallons of green goo.

It is classic Parry, and there is a very funny moment where the more experienced Pedro shows off his refined spewing technique: while Parry urges and spits, Pedro leans forward and lets it all flow smoothly out of him in one go, as if has turned on a dirty tap.

Before the big night in the deeply impressive village hall – Parry helps with the efficient collective effort to re-roof it, trying his best to match the locals’ skill in weaving leaves and reeds around wood – there are serious issues to confront. Outsiders are no longer killing or kidnapping the Waimaha, but they are tempting young villagers with a different way of life: children leave the rainforest and travel to school, where they are taught the Colombian national curriculum rather than the ways of the tribe.

As always, Tribe asks difficult questions about what western concepts such as progress and enlightenment really mean. Are the Waimaha who choose to leave their old life behind really better off for having greater access to tarmac, plastic, burgers, money and elections? An initiative to give Indigenous people educational autonomy within a wider system of governance looks like a decent compromise.

What we are really here for, however, is Parry losing his mind on drugs. At the community gathering, the Waimaha dance endlessly in circles, pounding the ground to send everyone into a trance-like state. The effect of this when combined with large quantities of yage, taken on an empty stomach, is something we don’t see much of, beyond Parry looking a bit peaky and leaning his forehead on a stick for support. But as he always does, he speaks lucidly about the new understanding the experience has given him of the forest way of life, and how precious is the place in which these people live. It is the same old same old, but it feels good to reconnect.

.png) 1 month ago

31

1 month ago

31