Donald Trump appears to be testing the boundaries of the power he can accumulate and then exert upon his allies, with a singular ambition: to coerce them into submitting to US supremacy. Though the president temporarily walked back his threat to unleash severe universal tariffs on Mexico and Canada, he has since imposed 25% tariffs on all steel and aluminium imports, which will primarily hit Canada, Mexico and China, and has announced a new plan for “reciprocal tariffs” on American trading partners. Above all, he clearly intends to wage a trade war against China. His brash, bombastic and belligerent threats reflect the reactionary political energy that drove his rise, which feeds on displays of dominance and disruption. His trade war won’t work to restore US economic dominance – but it tells us a lot about how both sides of the political aisle blame the US’s economic precarity on China’s economic ascent.

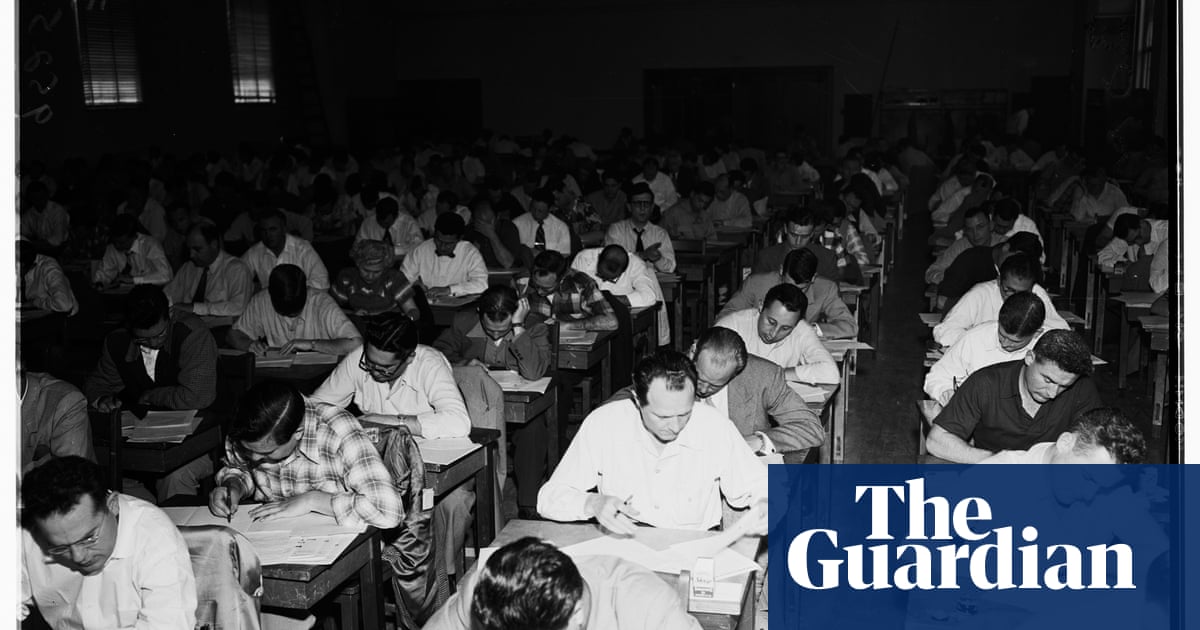

Over the past decade both Democrats and Republicans have blamed growing economic discontent on the sharp decline of American industry. The share of the US workforce employed in manufacturing has been in decline since the 1950s: today, just over 8% of American workers are employed in manufacturing, compared with 32% in 1953. The postwar era holds a powerful resonance for both the right and the left, and is often romanticised as a period when unionised male breadwinners in the industrial working class enjoyed far greater economic stability and prosperity than working and middle-class people do today. Viewed through this prism, since the decline of US manufacturing has occurred at the same time that China has emerged as a global manufacturing powerhouse, China’s gains equate to the US’s – and its workers’ – losses.

It follows from this that trade protectionism against China will restore manufacturing employment, re-establish American hegemony, and help to make the US economy great again for working people. And it’s not just Trump who has fallen for this story. The Biden administration largely maintained the average 21% tariffs against China that Trump imposed in his first term, expanding their scope to cover Chinese-made electric vehicles, silicon chips and lithium batteries. So far, Trump has imposed an additional 10% tariff on Chinese imports and may revoke a previous exemption for cheap direct to consumer purchases, with the threat that the US will further escalate if China retaliates. China, for its part, has already responded with far less aggressive but quite strategic levies, ranging from 10% to 15% on a selection of American imports including coal and crude oil, and put strict export controls on a list of critical minerals.

This escalating trade war may not result in the aggressive 60% tariffs on all Chinese imports that Trump called for on the campaign trail. But it will still exacerbate the problem that he is ostensibly seeking to solve. Tariffs work better on paper than they do in practice. While they can theoretically help to boost domestic manufacturing by subsidising the domestic producers of goods that Americans consume or trade abroad, broad-based tariffs actually function as an inflationary and regressive tax on middle and working-class people. In order for tariffs to boost manufacturing, corporations have to earn a profit from them, and decide to then increase investment to expand production. But there’s no guarantee that they will spend this surplus money on building new manufacturing plants and not on, say, increasing shareholder dividends.

And there’s no guarantee that tariffs will necessarily increase profits, either. In fact, since tariffs increase the costs of goods across supply chains, and create inflation that will probably lead to an interest rate hike, they may simply make the cost of production more expensive. Meanwhile, Trump’s tariffs on Chinese imports, together with the tax cuts that many people expect him to make, will probably do the opposite of boosting the US manufacturing sector, by strengthening the dollar – which will cheapen imports and make US exports more expensive and less competitive.

Taken together, all of these side-effects mean that Trump’s trade war will sow economic pain and do very little to support domestic manufacturing. One might imagine that this could play into the Democrats’ hands in the 2026 midterm elections. That would be misguided. Trump rose to power by leveraging the US’ politically explosive economic crisis. But he certainly doesn’t need to resolve this crisis to maintain popularity, nor for the Republican right to secure future electoral victories. If anything, he stands to gain more from stoking the flames, and channelling this anger into nationalism, racism, transphobia and misogyny. Reactionary politics feeds on and ignites resentment, and Trumpism works by appearing to continually upend the system while lashing out at enemies whom he claims are making Americans’ lives worse.

Trump’s return to power raises an even bigger question for progressives. Can boosting US manufacturing and reducing its trade deficit with China ameliorate the economic distress experienced by many Americans? Could a more tame, sane approach to trade protectionism help dismantle the new rightwing republic that Trump and his reactionary front are attempting to build? The Biden administration was explicitly betting on this. It sought to contain Trumpism by stoking a rapid post-Covid economic recovery – especially for the labour market. It attempted to boost domestic manufacturing by using light trade restrictions, such as more limited tariffs and export controls, and embracing industrial policy.

Bidenomics was an attempt to revive what the economic historian Gabriel Winant described in a recent interview as “a historic connection in the mid-twentieth century between productivity growth and manufacturing and the possibility of a more egalitarian labor market and social structure”. Back then, the rising productivity unique to manufacturing increased the wages, bargaining power and living standards of the working and middle class, without requiring further state-led redistributive measures such as increasing corporate taxation or creating European-style social welfare systems. As an anti-Trumpian project, Bidenomics rested on the assumption that American workers would be able to successfully press for higher wages amid a growing, reindustrialising economy, and that this would be enough to keep Trumpism at bay. This gamble did not pay off.

It would be shortsighted for the Democratic party to now abandon the good aspects of Bidenomics, such as public investment and support for full employment, and turn instead towards anti-China trade antagonism. The past decade of US politics and economic policymaking has been defined by the twinned force of pervasive economic distress and bipartisan consensus to refuse to address it head on. How can the US deliver affordable, universal and high-quality housing, healthcare and education? How do we make employment in the care and service economy – where the American working class now works – dignified and well-paying? How can we deliver rapid decarbonisation, end stagnation and reduce inequalities of wealth and power within and between countries? How do we wrest power from corporations and the wealthy towards everyday Americans? This is the stuff of class war, not trade war.

-

Melanie Brusseler is a political economist and the US programme director at the thinktank Common Wealth

.png) 2 months ago

33

2 months ago

33