Fifty years ago, on the day Papua New Guinea gained independence from Australia, a young law student lowered the Australian flag and raised Papua New Guinea’s for the first time.

The 22-year-old, Arnold Amet, had spent the preceding years active on his university campus, debating the merits of independence, petitioning future leaders to abandon the British monarchy, and imagining what it might mean for his people to finally govern themselves.

Then, on a fine September day in 1975, national sovereignty was no longer just a concept for discussion, it was real. Standing at the centre of Sir Hubert Murray Stadium in the capital of Port Moresby, Amet was overcome by emotion.

“That was an exciting, memorable time,” recalled Amet, who would go on to become the chief justice of Papua New Guinea and today serves as the country’s US ambassador.

“I don’t think that there were many dry eyes as we lowered the Australian flag and raised ours.”

But while Port Moresby celebrated with ceremony and song, another community regarded the new state with suspicion. Hundreds of kilometres away, in the highlands of Tari, local men with axes descended on a government station where the new flag had just been hoisted.

“As soon as the PNG flag went up, they didn’t pull the flag down – they chopped the whole bloody pole down,” recalled Chris Warrillow, who worked in Tari under the Australian administration.

What began that day in 1975 was not just just the transfer of power from Australia, but the attempted unification of more than 800 language groups under one sovereign Papua New Guinean state. The official line was “unity in diversity,” yet accounts on the ground point to a more fractured transition, some echoes of which are still being felt today. Though the country continues to face deep challenges, including social and economic hardships, many hold on to the promise and power of the moment of independence, fifty years on.

The path to independence

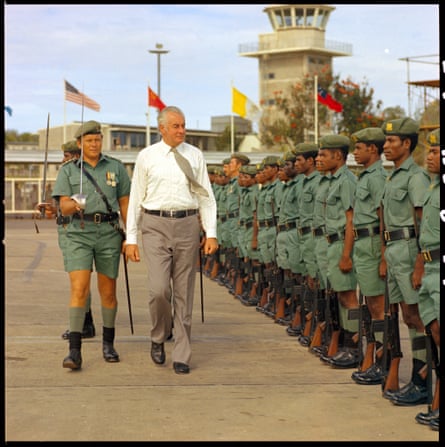

Australia had governed Papua New Guinea for decades when, in 1972, Gough Whitlam pledged on the campaign trail he would begin the transition to self-governance if elected.

“We believe it wrong and unnatural that a nation like Australia should continue to run a colony,” Whitlam said weeks before he was voted into power.

Once in power, Whitlam moved swiftly, granting PNG self-governance the following year and cementing a timeline for full independence by 1975.

In the 1970s, Australian officials held most senior positions in government, law, healthcare and education across the country – positions that were being handed over to local Papua New Guineans under the self-governance process.

While many of the educated class in the Port Moresby supported self-government, others in the provinces across PNG feared independence as another form of subjugation – by unfamiliar neighbours, in languages they didn’t speak, under a system that was foreign to theirs.

Amet was student council president at the University of Papua New Guinea, representing what he called PNG’s “urban educated elite” who saw themselves as the future leaders of the independent state.

“We were all excited about self-government and then independence, which was obviously distinct from our elders and many of our citizens in our provinces,” he said.

Outside the capital, some tribal leaders supported independence too and saw it as a way to reclaim authority over their customary land. In parts of PNG, some groups had long resisted Australian rule. They refused to pay taxes, demanding greater autonomy, and calling for early independence. That anger occasionally turned violent, like in 1971 when a senior Australian administrator was murdered by tribal leaders wanting to reclaim authority over their customary land.

Yet for most Australians working in PNG, the experience was different. Many felt broadly welcomed in the communities where they worked. Young patrol officers – known as kiaps – fulfilling the roles of police officers, and tax collectors, among other things, in remote areas.

Deryck Thompson, who in 1972 was part of the last intake of Australians to work as patrol officers in PNG, also took part in political education. He said the work was easier in coastal villages in the south-west of PNG where people had more exposure to foreigners. There, Thompson would use the analogy of PNG and Australia being like two canoes tied together, whose ropes would soon be cut so that PNG could be free to travel independently.

“Most local people hadn’t been out of their villages or that immediate area, and so they had really no understanding of what it would mean for the country to be independent,” Thompson said.

“They were really focusing on a day-to-day subsistence existence, and didn’t have time to sit down and discuss what may or may not happen in the outside world.”

There were concerns among some Australian administrators that they didn’t have time to prepare PNG’s remote communities for a future as part of a sovereign nation

“It was all a mad, last minute political education,” Warrillow said. “We were brainwashing, ‘You are getting [independence], you will have it, like it or not.’”

When independence came, most of the Australians working in PNG returned home, vacating the thousands of public posts, though some would remain as expatriates in the new country.

There was great hope for PNG new leaders in the years after those celebrations. But for many who lived through that moment, the country they imagined is yet to materialise, even 50 years on.

Terry Siik, who lives in Gerehu, was a teenager in 1975 and recalls standing with thousands of others to watch the flag-raising ceremony.

“I remember the cold air and the wind in the trees, when the flag rose, it felt like we were all lifted into a new future,” Siik says. He says life was simpler then, with “no fear on the streets.”

“We were poor but we had hope. We believed independence would bring a better life,” the 66-year-old says.

Since 1975, PNG’s population has more than quadrupled, though employment opportunities haven’t kept pace. Rates of illiteracy, malnutrition and preventable disease also remain widespread, while the vast majority of citizens see government corruption as a problem.

“They are struggling, whereas we were privileged to have jobs that we could just go into as we chose,” Amet said.

In Geheru, Siik says more than 30 people live in his small house and his children can’t move out as housing is too expensive.

“We dreamed of a better future for them, but now I wonder, was it worth it?”

Still, every Independence day he raises the flag outside his home.

“I raise it not because everything is perfect, but because of the dream we had back in 1975 and the hope that one day our leaders will remember what it means.”

Rebecca Bush contributed to this report

.png) 2 months ago

60

2 months ago

60