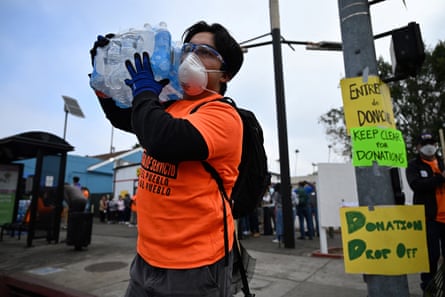

When Edward Kelly, the president of the International Association of Fire Fighters (IAFF), toured the wildfire destruction zones in the Pacific Palisades and Altadena neighborhoods of Los Angeles last week, he saw thousands of homes burned to the ground. “The level of devastation is apocalyptic,” he said.

Propelled by hurricane-force winds, the flames that tore through Los Angeles earlier this month left little more than ashes in their wake, destroying more than 12,000 structures and killing at least 25 people.

The disaster kicked off a fierce debate over LA’s firefighting resources and preparedness. Officials argued over whether the fire department budget should have been higher, and whether the city’s water infrastructure could have been updated. It’s also not clear yet whether the Palisades fire could have been controlled if fire engines had been deployed faster.

The Los Angeles fire chief, Kristin Crowley, said she felt the city had let her department down. Crowley has faced questions over her deployment decisions before the fires, and whether the Palisades fire could have been contained earlier. Kelly, of the IAFF, said he knew the department is struggling. “They don’t have enough firefighters,” he said.

But many experts, including Kelly, point out that as the climate crisis turbocharges wildfires, adding firefighting resources alone won’t be enough to save homes – and lives.

“Our current dominant model is to invest in reactive wildfire suppression, and the costs are just soaring,” said Timothy Ingalsbee, co-founder and executive director of Firefighters United for Safety, Ethics and Ecology (Fusee) and a former wildland firefighter.

“The problem is we surpassed our human limits to prevent or put out all wildfires, particularly during these extreme wind-driven weather events that have a link to climate change.

“We surpassed our human limits to stop this,” he said.

‘Siege-like suppression’

Fire has always been a feature of California’s landscape, but the region is on a path to larger and more devastating wildfires. Global warming is making the wildfire season longer. But firefighting tactics in the past century are playing a role as well.

Since settlers arrived in the west, the approach to fire has grown into a “model of siege-like suppression”, said Ingalsbee.

As fires have grown larger, so have the budgets to control and contain them. This approach is not economically sustainable, Ingalsbee said: “We’re spending more and more money having less and less effectiveness in the goals of protecting homes from burning down.”

Ingalsbee said once they grow, fires such as the ones that overwhelmed Los Angeles cannot be stopped, even with more personnel, air tankers and engines. “No amount of money – you could quadruple that budget, and you would not be able to stop those fires and prevent the spread during these extreme conditions,” he said.

We need to shift to a proactive model that accepts fire as part of the landscape and mitigates risk with fuel management, like prescribed burns, he said. “Instead of fire suppression, [we need] fire management and re-engaging with fire, which makes a great ally,” he said.

“This has got to be a society-wide cultural shift that we have to stop looking at this vital force of nature as something we can conquer or control, and learn how to live with it,” he said.

Indigenous land management

Los Angeles is located on the traditional lands of the Gabrieleno Band of Mission Indians. Matthew Teutimez, the tribe’s biologist and a tribal member, said he felt heartache seeing the fires tear through his homelands.

“What has been a tinder box ready to burn has now burned,” Teutimez said. “Unfortunately, it’s something that wasn’t a surprise, but it is a catastrophe.”

From his perspective, non-Indigenous land management practices helped to set the stage for the destructive fires.

Before European settlers arrived, there were fires that benefited the ecosystem, and native plants evolved to live with fire. Indigenous people set small fires to care for the landscape, until the practice was outlawed. The fire suppression model that displaced Indigenous practices allows vegetation to build up and create fuel for wildfires.

Native plants are used to the cycles of extreme wet and dry that are normal in southern California, but invasive plants such as mustard and thistle respond differently, Teutimez said. When intense rainfall happens, invasive plants suck up large amounts of water and quickly grow. When a period of drought follows, the invasive plants dry up and become kindling.

“This kindling was never part of our system, but now you have kindling everywhere,” he said. “Until we take away that kindling, we’re never going to have natural fire cycles that used to benefit our land.”

Climate change is making wet and dry periods more intense, but it is not the only factor in destructive wildfires, he said. “What climate change is doing now is making those cycles a bit more dramatic, a bit more extended, but those cycles have always been here and will always be here,” he said.

Teutimez said the way forward was to restore the Indigenous relationship with the land. That means removing invasive plants and keeping native plants that benefit the ecosystem. “Just by removing non-natives, you are making your landscape more resilient.”

Significant investment up front

The kind of fuel management that is required would cost a lot up front, but lower overall costs over time.

“I don’t have a dollar figure. It will be very expensive, but more effective, more sustainable, and the costs of suppression will lower over time,” Ingalsbee said.

Fuel management and home hardening reduce fire risk but do not eliminate it entirely, Ingalsbee added. Southern California’s landscape is fire-prone, and there will be fire one way or another. That said, there are areas that are higher risk – with steep slopes covered with chaparral. “These are indefensible locations,” he said.

It’s a difficult problem to solve, he said, because there are already people living in those areas. But the first step is better land use planning and zoning. “We should put a halt to building [new homes] in extreme high-risk fire-prone areas,” he said.

Joe Ten Eyck, wildfire/urban-interface fire programs coordinator for IAFF, said prevention such as fuel management and home hardening would have high costs and would not fully prevent large fires, but it would prevent widespread destruction. “On a local level, you’re getting into a few hundred million dollars,” he said, adding that state and federal governments would also need to budget for prevention.

Eyck said that although prescribed burns were happening, they were not happening nearly enough. Sometimes that’s because the weather windows when they can take place are brief, because of local opposition, or because regulations and time get in the way. For instance, the air pollution control districts push back against prescribed burns because it affects air quality. “It needs to be expanded, and then the regulatory barriers that are in place need to be addressed to make it easier to get their work done,” he said.

Teutimez is not optimistic that the Los Angeles wildfires will be a turning point for fire policy. “You’re going to have those that are in decision-making ability, that have not been affected, that are going to look at the bottom line,” he said. “So [policymakers] are going to make decisions that continue this pathway that we’re on of destruction.”

He called on policymakers and homeowners to include Indigenous people in land management practices.

“Those that are managing the land have allowed it to build up to this level that now any sort of fire on it leads to catastrophe, and that’s something that we as a tribe want to help change. We know how to manage our land so that fire isn’t catastrophic – it’s beneficial,” he said.

Kelly, the IAFF president, said budgets must increase staffing for firefighters and also include more money to manage fuels to mitigate risk. He emphasized that the Los Angeles fires were a wake-up call. “We need to be thinking differently,” he said.

.png) 3 months ago

40

3 months ago

40