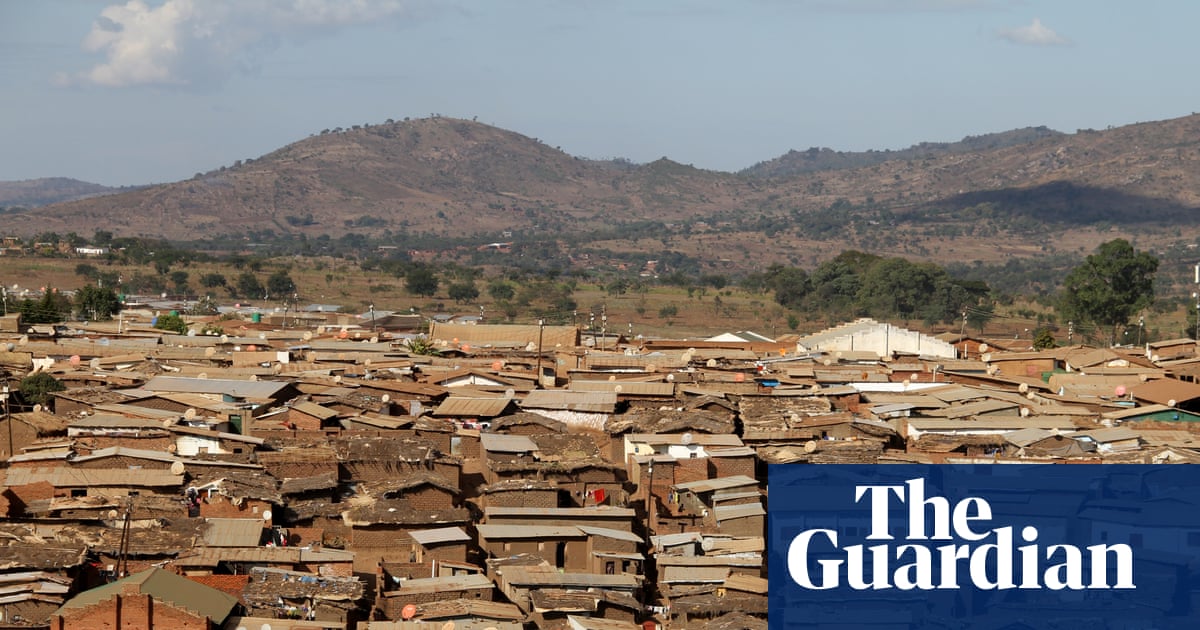

The ironworks in Saudi Arabia’s coastal city of Dammam has had an unusual journey: it has crossed the Atlantic Ocean – twice. It was moved to Saudi Arabia in 2006 from Alabama, US. Before that, the plant’s home was in the UK.

The plant can produce about 1m tonnes a year of direct reduced iron (DRI), a material that can be used in green steel production. Decades after the plant left the UK – shipped in 28,000 pieces – British ministers are now considering reversing course and funding a similar facility once again.

However, the government’s DRI ambition is controversial within the British steel sector; the lobby group UK Steel told the Guardian that a DRI plant was not its priority. Senior industry insiders said they were concerned that hundreds of millions of pounds of taxpayer money may be spent on funding a “white elephant”.

The government last month recalled parliament to pass emergency legislation to take control of British Steel’s two blast furnaces at Scunthorpe, amid concerns its Chinese owner, Jingye, was days away from closing it. The business secretary, Jonathan Reynolds, and the industry minister Sarah Jones said the effective takeover was necessary to preserve the UK’s ability to produce “virgin” or primary steel from iron ore.

The Scunthorpe blast furnaces, known as Queen Anne and Queen Bess, are the last two operating in the UK. However, despite receiving materials supplies for several months, they are running out of time, and ministers are hoping to find a way of retaining primary steelmaking abilities.

Blast furnaces use the carbon in coal to strip oxygen from iron ore. That process eventually results in carbon dioxide being vented into the atmosphere, where it heats the globe. Many steel companies are switching to much cleaner electric arc furnaces, which use electricity to melt down scrap steel. However, they cannot produce iron from iron ore.

That is where DRI could come in. The process strips out the ore’s oxygen using gas. While the vast majority of DRI uses methane, resulting in carbon dioxide being released into the atmosphere, switching to using green hydrogen could allow iron production without significant emissions.

Ministers have repeatedly cited DRI as a strong contender to receive part of a £2.5bn fund for a new steel strategy. Reynolds last month told parliament: “Direct reduced iron technology is of significant potential interest to us for the future.”

Yet, within the industry the idea is seen as a lower priority than reducing energy costs and preventing a flood of metal imports diverted to avoid Donald Trump’s tariffs, according to lobby group UK Steel and several industry executives.

Several executives and industry experts have raised significant doubts over whether a new UK DRI plant, costing up to £2bn to build, would provide good value for money.

The owners of the two biggest steelworks, Tata Steel at Port Talbot, Wales, and British Steel at Scunthorpe, are not thought to be interested in sourcing the huge DRI supplies that would justify a plant. Other, smaller producers such as Celsa in Cardiff and Liberty Steel at Rotherham could use DRI, but do not need to.

Energy costs

UK Steel said it would be better to focus on reducing sky-high energy costs at existing plants to match rates in France and Germany than on subsidising an expensive new facility. As the Saudi plant’s trajectory shows, DRI plants have tended, like much heavy industry, to cluster in countries with abundant, cheap energy. The UK has some of the highest industrial energy prices in the world.

“The UK steel industry is in crisis, facing uncompetitive market conditions, shrinking demand, and global trade pressures,” UK Steel said.

“While the steel strategy is an opportunity to formulate a long-term vision for the sector, the government must also assess how its finite resources are best allocated at this point in time. Addressing urgent issues like electricity prices and trade defence must clearly take priority in order to put our sector on a sustainable footing.”

The trade body said that efforts to assess how to meet future demand for steel would include assessing the need for – and viability of – a UK DRI plant, adding: “Energy costs and access to affordable hydrogen will underpin this assessment, balanced against investing in new capabilities, energy efficiency, and productivity improvements.”

after newsletter promotion

UK Steel said there would be an “opportunity cost” to spending on DRI, while still remaining reliant on imports for iron ore.

The government’s steel council, which brings together ministers, unions and businesses, discussed DRI in detail during the British Steel crisis, to the frustration of some in industry.

“It’ll just become a white elephant,” said one senior figure in the industry. New DRI plants usually only employ about 200 people.

Crisis backup

However, union leaders and many MPs believe that virgin steel is crucial either for making weapons in case of war, or for economic resilience in crises such as pandemics. Saudi Arabia is the only member of the G20 group of developed economies that does not have blast furnaces to make iron for steel production. But its two DRI plants mean it could theoretically, at a pinch, keep producing iron and therefore steel.

Alasdair McDiarmid, the assistant general secretary at Community, a union representing UK steelworkers, said there was a strong case for DRI investment.

“Investment in DRI can make our steel greener and more competitive, while maintaining the UK’s primary steelmaking capability, which is so crucial in our volatile world,” he said.

“DRI is fully compatible with electric arc furnaces and would make them more sustainable by delivering a secure, homegrown supply of metallics, and allowing for the future adoption of hydrogen-based steelmaking.”

The UK government is awaiting a report on DRI by the Materials Processing Institute, a Middlesbrough-based research organisation, which is expected to recommend DRI as necessary to maintain primary steelmaking. Ministers will have to weigh up whether to heavily subsidise a plant to attract a private-sector investor.

“People see it as a bit of a red herring,” said one industry leader. “Stop going on about this DRI stuff. If you’ve got limited resources, you would probably do something else.”

.png) 3 months ago

99

3 months ago

99