Santiago Yahuarcani is the leader of the White Heron clan of the Uitoto Nation, an Indigenous population of the Amazon basin in Peru and Colombia. He uses his work to preserve the history of his people, confront the violence they have had to endure, and fight for a future that is relentlessly under threat. In his paintings, celestial beings dance in starlight. Hybrid creatures – part-human, part-dolphin – wade through rivers. Bodies meld with nature and jungle melds with body. These dizzyingly shamanistic paintings of mythological creatures and Indigenous spiritualism are a celebration of his home, his people and his past.

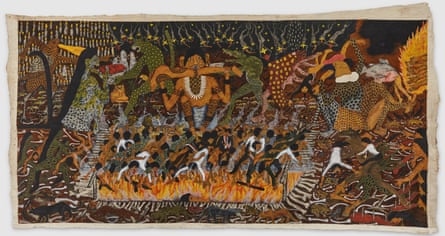

The show opens with three vast, chaotic paintings on traditional bark canvas, a rough, dense material that he painstakingly hammers flat with a machete. Each work is filled with a whorl of licking tongues, gawping mouths and endless hybrid creatures. A woman with webbed fingers and scales down her back gathers fish in her arms as a man inhales big clouds of smoke being puffed out by a grey figure with crab claws for hands. Rocks have eyes and teeth, birds become lizards, fish brandish spears. If it sounds like it’s fuelled by hallucinogens, that’s because it is: medicinal plants like ayahuasca, as well as coca and tobacco, are an integral part of Uitoto culture.

Yahuarcani’s wild visions are filled with references to creation myths, to the way rivers, animals and forests are carriers of memory. Spirits are everywhere, their stories passed down by elders in ritual storytelling sessions (Yahuarcani comes from a family of artists). He paints a world where man and nature flow into each other, inseparable, interrelated, interconnected.

A lot of the works have a direct narrative. An image of coca and tobacco leaves tells the story of Moo Buinaima, the father creator whose tears allowed humanity to walk the earth, with those sacred plants allowing communication between the Uitoto and the divine. A figure with splayed bird feet is Juma, the heron man, Yahuarcani’s first ancestor, responsible for Moo Buinaima. A painting of hands describes the way Uitoto-Aimeni counting works. A whole system of knowledge is delineated, a whole history of humanity is told, in swirling patterns of brown, red and blue.

But one presence looms darkly over all of this: colonial violence. Bodies are thrust into a pit of fire by figures brandishing machine guns in one painting. A woman bleeds an endless stream of white fluid in another. More than 30,000 Indigenous people died between 1879 and 1912 at the hands of the Peruvian Amazon Company. It brutally exploited the people and the land for profit, and the pain of those atrocities – experienced directly by Yahuarcani’s grandfather – endures in these paintings.

More modern threats appear too, as Covid is depicted as a furry monster ravaging the world. But throughout all of this shocking imagery, Yahuarcani’s work is still filled with leopards, crocodiles, pink dolphins and gods, figures resisting, fighting the onslaught of exploitation and violence. These fantastical creatures represent his land, his people, his history all surviving despite the adversity they’ve faced.

Yahuarcani’s work is intricate, detailed, colourful and passionate. It tells important, powerful stories, and it tells them urgently. But you have to tread a fine line here, being careful not fetishise the work or Yahuarcani’s background – yet at the same time, you can’t just view it all through the lens of western art history. It’s not good because it looks like western painting, and it’s not good just because it tells a story that’s incredibly affecting. It’s good because it’s relevant, because it’s emotional, because it’s an artist using painting as a tool of survival, endurance and communication.

At a time when Indigenous cultures are increasingly under threat, Yahuarcani’s work feels necessary, crucial. It doesn’t hurt that it’s also deeply beautiful and hugely moving.

.png) 2 months ago

15

2 months ago

15