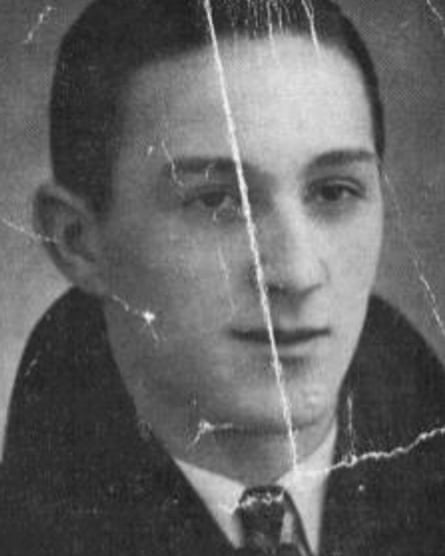

Christel Van Iseghem was sitting in a radio studio when she heard the last words of her great uncle Norbert, murdered by the Nazis for his role in the Belgian resistance.

“My heart stood still,” said the 71-year-old from Kallo in Flanders. “This was something I didn’t know existed. I sat there shaking, my hands trembling … It means so much to me. He will not be forgotten.”

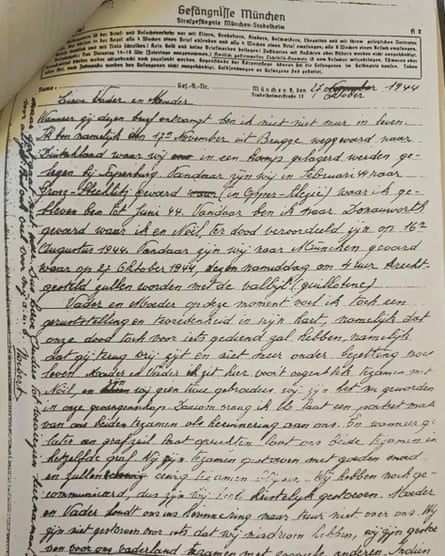

Before his execution in Munich on 27 October 1944, alongside his friend Noël Boydens, 19-year-old Norbert Vanbeveren wrote to his parents that he felt “a kind of peace and satisfaction in my heart, because our death will have served a purpose after all: that you are free again and no longer have to live under occupation”.

Vanbeveren was one of 1,500 Belgian resistance fighters allowed to write to his loved ones before the Nazis murdered him. His letter is one of about 20 that recently surfaced thanks to the Last Words project, a collaboration between the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), the Heroes of the Resistance remembrance association and 15 volunteers, adding to an archive of some 350 letters.

Dany Neudt, co-founder of Heroes of the Resistance, read aloud Norbert’s words on Belgian radio and is calling for a reappraisal of resistance groups, whose heroism he believes was forgotten in a traumatised silence after the war, while collaboration – including by Flemish nationalists – was seen more sympathetically.

Neudt posts every day on social media the story of one “hero” and organises “resistance cafe” evenings to share their tales. He wants more people to search attics and archives for examples of these letters of last words. “War brings out the worst in people … but also the best in humanity, and that is what you see in the stories of resistance.”

The liberation of Belgium had begun by the time Vanbeveren was killed, but his father was dead and the letter did not reach his mother. Van Iseghem, his great niece, was the first family member to hear his words, eight decades later.

Neudt’s search for this archive began after his father died during the pandemic and he began researching his grandfather, Henri Neudt, part of the Geheim Leger [secret army] resistance group, who narrowly escaped deportation to Germany on the “ghost” train. “It was the last train going to the Neuengamme concentration camp, but was attacked by the resistance and went back,” he said. “My grandfather was on that train but nothing was ever said in my family. What a strange situation it is that in Flanders, we know about collaborators but we don’t know names of people in the resistance. Even for me, as a historian, this is a blind spot.”

Many modern historians believe the fragmented Belgian resistance movement suffered a postwar image problem, according to Nel de Mûelenaere, VUB professor of contemporary history and chair of the Traces of the Resistance project. “The Flemish-nationalist collaborators, more unified and with support of Flemish-nationalist and Catholic politicians, falsely portrayed themselves as misled young men who were seduced by anti-communism and unjustly punished after the war by the resistance, who were opportunists, criminals, communists,” she said. “In France, you had General de Gaulle, the idea that France liberated itself by the resistance; in the Netherlands you have Hannie Schaft. In Belgium, it was very much a fractured movement and fractured memory … [of] trauma and repression.”

Others, like Ellen De Soete, whose uncle, Albert Serreyn, was executed, argue for a revival of the 8 Mayliberation day public holiday. “Especially in Flanders, there was a lot of collaboration, and some political parties thought if the stories were forgotten, in a few generations people would not know,” she said. “It was a way of wiping stories from the collective memory. But now young people do want to know, and a new wind is blowing.”Dr Samuël Kruizinga, historian of 20th-century war and violence at the University of Amsterdam, said reviving resistance stories could be a way for Belgium to move away from black-and-white thinking. “Acts of resistance were after the second world war quite consciously framed as acts in favour of the Belgian unitary state,” he said.

“There’s also the memory of the first world war where Belgium is also under German occupation, and the formal instructions given to Belgians by the government in exile were that swift resistance will only provoke retaliation. This is very consciously trying to reframe and rediscover the enormous personal heroism of people resisting Nazi rule.”

De Mûelenaere said that with talk of war in western Europe returning, these letters resonate. “I was reading one yesterday evening, and it was of a man who lived in a little village very near where my family is from,” she said. “At the end of the letter, it said: greetings to the family de Mûelenaere. It’s a world we can almost touch. We need those stories … and the almost healing idea that ordinary people said no to an authoritarian regime.”

.png) 1 month ago

14

1 month ago

14