On 11 June 1988, I was 12 and sitting with my family watching the Free Nelson Mandela Concert on TV. As a clan, we were old hands at trying to free Mandela, having done our fair share of marching and boycotting over the years, and this concert felt like the culmination of all that. There was a lot of excitement in the room: we squeezed on to the sofa and opened the windows wide. (If the wind’s blowing in the right direction, you can hear a Wembley audience roar from Willesden.)

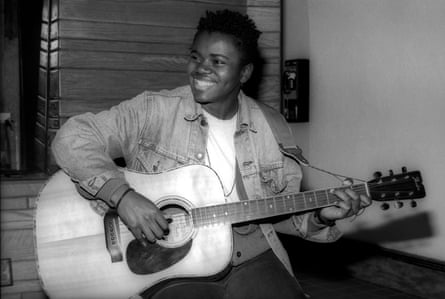

Many world-famous musicians played that day. Most of them I don’t remember, but one I will never forget: Tracy Chapman. I think a lot of people feel that way, though when you rewatch the footage you realise what she was up against at the time. Nobody cheers as she takes the stage. In fact, the crowd seem hardly aware she’s arrived. People are chanting, chatting or just partying among themselves.

Drafted in as replacement for Stevie Wonder – who had last-minute technical issues – it must have taken a lot of courage for an unknown 24-year-old to play in front of 90,000 people, not to mention a worldwide television audience of 600 million. And on the first line of Fast Car, her voice does break, a little. For a moment, you spy the Harvard Square busker she’d so recently been, demoralised by all the commuters and the students rushing by …

But a second later, she has everybody’s full attention. Now there is only her guitar, the melody, the words. I want a ticket to anywhere / Maybe we make a deal / Maybe together we can get somewhere. It’s such an intimate, unexpected performance. Bombastic music was in style, and Wembley in particular was the home of spectacle and theatrics. Chapman was something completely different: a protest singer with an acoustic guitar. It’s wonderful to watch that mammoth crowd fall into an awed silence.

Back in Willesden, we were pretty stunned too, although perhaps for different reasons. For us, it was the shock of the familiar. She was dressed just like the young activists you saw on the marches – black cowlneck T, black jeans, black boots – and she even looked like our mother: no makeup and the same three-inch dreadlocks. She was so … familiar. We also recognised the musical lineage. That rich alto timbre. It was like listening to the daughter of Joan Armatrading.

But what was such a person doing on television? That really felt unprecedented. And she didn’t just look like the people on our side of the screen, she was singing our songs. Songs of everyday struggle, working-class experience, poverty, drink, political protest, domestic troubles, thwarted dreams. She was talkin’ about a revolution. On the BBC!

In 1988, we lived in a monoculture. By the end of that summer, it seemed like pretty much everyone who had any interest in music at all had made a pilgrimage to Woolworths or Our Price and bought her debut album, Tracy Chapman. By autumn, those 11 songs had buried themselves deep into so many people’s lives, affecting our political thinking, romantic dreams, existential beliefs, Top 10 lists. All because of that one performance.

None of this was typical. Most artists of that period had juggernaut PR machines around them, but with Chapman the communication was singular and direct, from singer to eardrum, and nothing could get in the way of it, and nothing extra was needed to amplify it. For years after that concert, I don’t recall reading a single interview with her, and I don’t think I saw her perform again until she sang Fast Car with Luke Combs at the 2024 Grammys.

For years, the only photograph I’d ever seen of her was the one on the front of that first album. Yet despite knowing next to nothing about her, I and millions of others have been listening to her for decades. When you write songs like Tracy Chapman does, you don’t really need to do anything else but that. Her debut is the articulation of this principle: 11 perfect songs, with no fat and no filler, driven by a clear unity of purpose that announces itself from the get-go and never lets up.

This is an album about “the people”. They are addressed directly in Talkin’ Bout a Revolution, and kept in mind throughout: the labour they perform, their hopes and aspirations, the loves they’ve gained and lost, their mistakes and shames, even their crimes. Lyrically, they are known but never idealised. They are certainly the working poor but they are more than the “proletariat”. They are also human beings. Full of human contradictions. Sometimes, for example, they want “mountains of things” instead of freedom. Not infrequently they do dangerous or dumb things, or make poor decisions that make their already hard lives worse. Behind the wall, a man beats his wife. Love ennobles the people, as it ennobles everybody, but love also just as often gets disrupted or crushed by the pressing demands of sheer survival.

What is never forgotten, not even for a line, is how the American game is rigged against them, at every turn. Working them half to death for the minimum wage, or creating division where solidarity is required: Across the lines / Who would dare to go / Under the bridge / Over the tracks / That separate whites from blacks?

One of the things that most moved me about this album was not only its challenge to the segregated politics of American life, but its reclamation of the unity of American music. Now that Beyoncé can top the country charts and we have musicians such as Rhiannon Giddens performing with equal expertise at the Newport folk and jazz festivals, it’s sometimes hard to remember how rigidly binary the American music business was in the 1980s and 90s. It was incredibly difficult back then to imagine a folk singer with a guitar existing outside of the paradigm set by Bob Dylan. Hip-hop could be and often was “protest music”, but black women were soul singers or pop stars. We could sing the blues and jazz, but folk was another country. Chapman went across all these lines, singing passionately about one country and the working people who live there, employing a stripped-down production that still feels profoundly radical.

There’s never a good moment, I’d imagine, for a young artist to explain to their record label that they want to record an a cappella lament about domestic violence. But somehow, on Tracy Chapman, there it is: an unforgettable human voice, untampered by anything else, singing an excruciating truth. It won’t do no good to call / The police always come late / If they come at all.

The poor people described in Tracy Chapman do not have all the answers, but they are hungry for truth. They don’t want to be lied to any more, not by politicians or employers or neighbours or lovers. The truths they want to hear are not particularly complex but they are essential. That’s the job of a protest singer, in my view: to remind technocrats and politicians and all those who hold power of the fundamental concerns of the people.

Listening to the track Why? now, as this masterful album is rereleased, it’s astonishing how few answers we presently have to Chapman’s basic questions: Why do the babies starve? / There’s enough food to feed the world / Why when there are so many of us / Are there people still alone? // Why are the missiles called peacekeepers / When they’re aimed to kill? / Why is a woman still not safe / When she’s in her home?

That simple, honest language is the tool of the protest singer. The Orwellian doublespeak that follows, meanwhile, is all too familiar, and continues to be employed at the highest levels of American power: Love is hate / War is peace / No is yes / We’re all free.

Chapman’s sheer melodic beauty and committed, generous lyrics are a gift to her listeners. But I feel that her career – which started with this extraordinary album – has also served as a startling and humbling example to artists. She reminds us that an artist can pursue an individual course without being individualistic. That she can speak to many without necessarily speaking to the press. That there is such a thing as privacy, and that every human being has a right to it.

Finally, and most vitally, that a soul is something worth holding on to. In fact, it’s pretty much all that you have.

.png) 1 month ago

25

1 month ago

25