Two seemingly contradictory things are true. It was appalling for the UK’s domestic policy agenda to be hijacked last week by Elon Musk’s blaze of interest in child sexual exploitation gangs. And government action in response to the independent inquiry into child sexual abuse was long overdue. As ministers look in more detail at plans announced in a panic, it is essential that the many anxieties surrounding group-based child sexual exploitation – euphemistically known as “grooming gangs” because of the techniques used to ensnare vulnerable girls – do not distract from the seriousness of the issue.

On Friday, Andy Burnham, the Greater Manchester mayor, added his voice to those calling for a new inquiry into child sexual exploitation – a specific form of abuse carried out in exchange for money or other things that victims want or need; and often involving financial advantage for perpetrators, who traffic children under their control. A large majority of group-based child sex offences (83% in 2023) are committed by white men, although some areas have a problem with gangs of mainly Pakistani-heritage abusers. It is true that the inquiry’s broad remit did not include a thorough investigation of child sexual exploitation specifically. There are many gaps in the data, as multiple reviews have noted.

Whether or not they pursue the idea of a new national probe, ministers are likely to struggle with the pledges made last week. Criminalising the failure to report suspicions of child sexual abuse or exploitation is tricky, as the last government found when it tried. Difficulties surround both the issue of scope – who exactly would face these new sanctions – and thresholds. For example: will it become a crime for a youth work volunteer not to tell police if a 15-year-old girl says she has had sex with a 17-year-old boyfriend?

Because 16 is the age of consent, treatment by public authorities of girls on either side of that threshold differs. Bluntly, 16- and 17-year-old girls do not qualify for the same degree of care and protection. This ambiguity around the status of older teenagers can be seen clearly in official crime data, where they are grouped with adults. The government’s pledge to follow the independent inquiry’s recommendation for a new child sexual abuse dataset should mean that further light is thrown on this troubling area.

Convening a victims’ and survivors’ panel to oversee reform, as ministers have also pledged, ought to be reasonably straightforward. So should making grooming an aggravating factor in sentencing, although this brings the vexed issue of prison overcrowding into frame. Already, the government has had to backtrack on one of its flagship measures to reduce violence against girls and women. A pledge for specialist rape courts was put off due to a lack of lawyers. The reports on Rochdale and Rotherham showed how vital local youth and sexual health workers were in exposing what was going on. It is alarming to realise that cuts in these areas could mean girls are even more exposed now than before. Support and supervision for police and social workers should also be prioritised.

There is no question that victims of these crimes have been badly let down, over decades, by police, councils, politicians and media organisations. It is easy to see now that the decision taken more than 20 years ago to delay transmission of a Channel 4 film featuring coverage of a grooming gang because the BNP had endorsed it was a mistake. The film, like later reports, found that concerns about community cohesion, and people’s fears of being seen as racist, inhibited action in some cases. It is right to be outraged by this and disgusted by reports about the sadistic gang-rape of children. But disturbing though these crimes are, they must not distort discussion of sexual abuse overall.

Group-based abuse, including exploitation, made up 3.7% of the 115,489 child sexual offences reported to police in England and Wales in 2023. More than a quarter of that 3.7% were family-based crimes. And while calls for new research on exploitation specifically should be taken seriously, not every story about past failures is true. Last week, BBC Verify traced one widely amplified claim, that the Home Office had issued an edict against investigating grooming in 2008, and showed it to be false.

There is another important element to these attacks on the government and efforts to link the subject of child sexual abuse with immigration. Mark Zuckerberg’s announcement that his company, Meta, would drastically cut back on factchecking and moderation was not immediately connected to Musk’s interest in child abuse. But the two stories are related by more than timing. Because while it clearly suits US tech billionaires, and rightwing populists such as the shadow justice secretary, Robert Jenrick, to pretend that child sexual exploitation is an import from faraway lands, the truth is far more troubling and complex.

Multiple factors lie behind sexual offences against children. Some are economic, others are ideological. Consideration of the beliefs and opinions that influence men’s attitudes and behaviour, including those derived from religion, must never be off limits.

But it would be a colossal misjudgment for ministers, or anyone else, to ignore the role of the internet in propagating sexual abuse and exploitation. Far from being a “medieval” relic, as Jenrick suggested last week, all the evidence points to such abuse ballooning in 21st-century online spaces. One recent report by academics highlighted the risks in the US, where one in nine men admitted committing online child sexual abuse offences. In the UK, the figure was one in 14. It concluded that 300 million children globally are at risk. A disturbing volume of such offences are now committed by children themselves.

Some of the most egregious abuses have been on pornography websites such as Pornhub, and the one where Gisèle Pelicot’s husband recruited more than 80 strangers to rape her (the computer engineering graduate who set up this site has been arrested). But Meta/Facebook has faced a stream of criticism from whistleblowers and experts, while X was fined by the Australian government for failing to cooperate with anti-child abuse efforts.

Two of the independent inquiry’s recommendations were for tighter internet laws. Last week, the government announced that the taking of intimate images without consent and the making of explicit deepfakes are to be criminalised. But the code launched by Ofcom in December setting out how businesses comply with the Online Safety Act is full of holes, with no general duty on companies to improve safety.

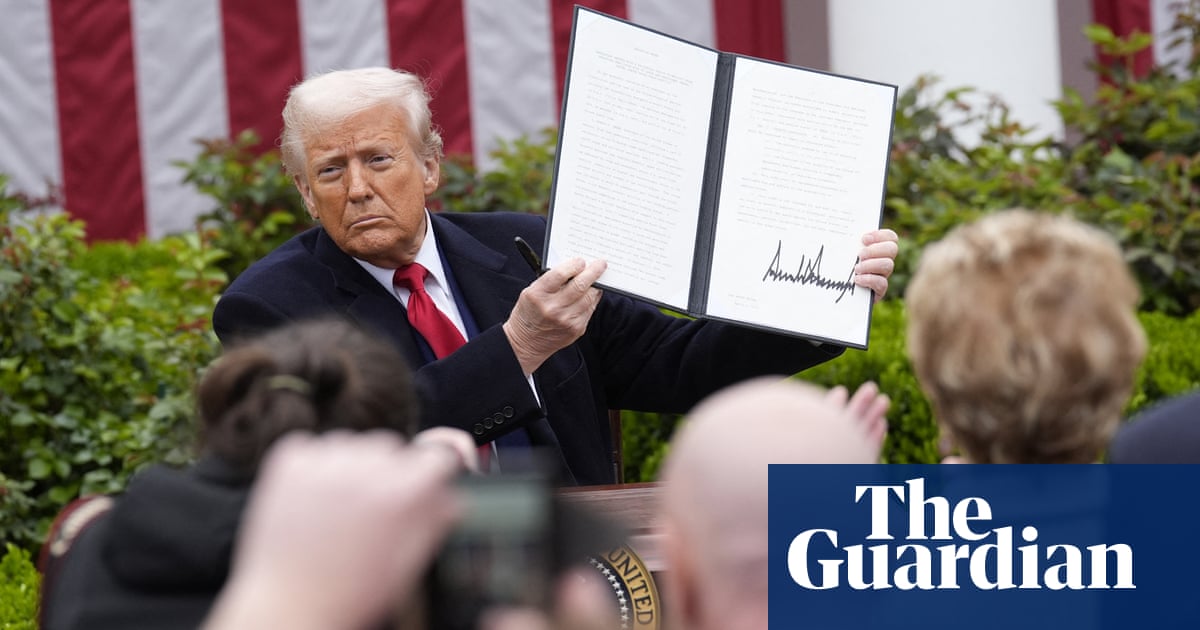

This, of course, is just as the industry wants it. It has consistently pushed back hard against restrictions on encryption and calls for age verification to protect children from pornography. Now, all the signs point to a renewed and aggressive anti-regulation drive under Donald Trump. And while factchecking and moderation are not the same as screening for illegal material, Zuckerberg himself said that the changes mean “we’re going to catch less bad stuff”.

Undoubtedly there is more to be learned about Britain’s sexual exploitation gangs. But if politicians are serious about child protection, they must look to the future as well as the past, and insist that the virtual world is policed along with the real one.

-

Susanna Rustin is a Guardian social affairs journalist

Do you have an opinion on the issues raised in this article? If you would like to submit a response of up to 300 words by email to be considered for publication in our letters section, please click here.

.png) 2 months ago

24

2 months ago

24