What must it have felt like to watch Sarah Kane’s final play, whose depressed protagonist plots imminent suicide, knowing that the playwright killed herself the previous year?

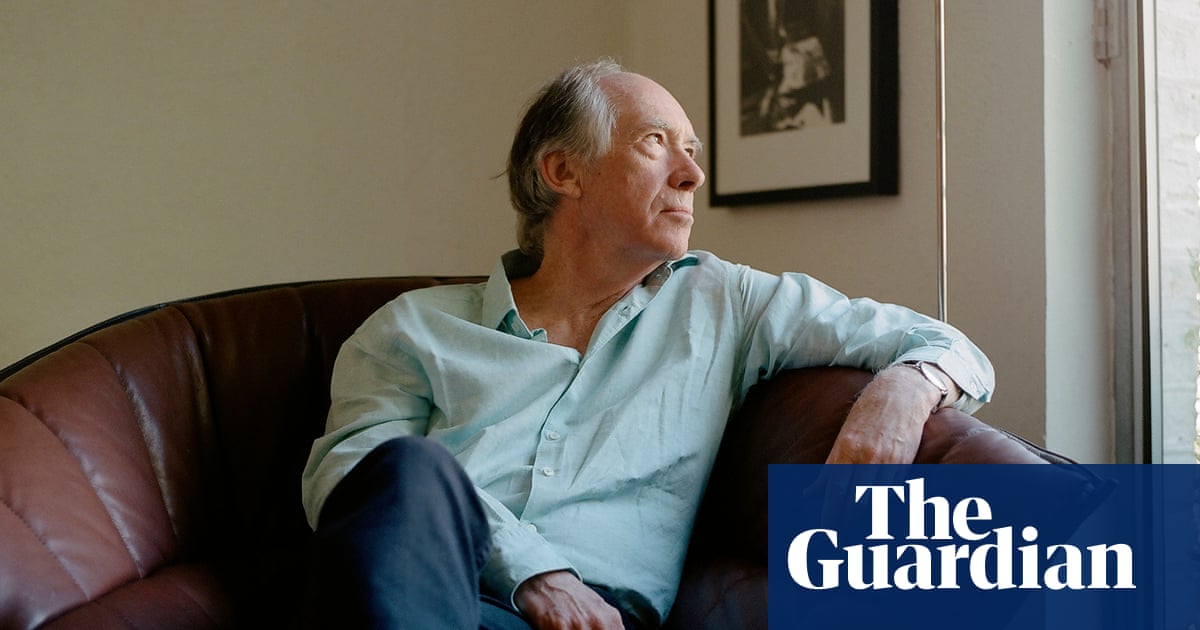

First staged in 2000, under the shadow of Kane’s death in 1999, it is back now with the original creative team, including director James Macdonald and its fine three-strong cast of Daniel Evans, Jo McInnes and Madeleine Potter. They play a divided self, it seems, reflecting on illness, shame, self-loathing, love, betrayal, medication culture and – importantly – the prospect of ending it all at exactly 4.48am.

Co-produced by the Royal Shakespeare Company, the play is again staged in the upstairs theatre at the Royal Court (after which it will travel to Stratford-upon-Avon). It is variously abstruse and lucid in its arguments on life, death and suicide, and still original in form. But this production feels like the reconstruction of a seminal performance rather than a seminal performance for today. Maybe this is because Kane’s position has changed in the intervening decades: she sits firmly in the canon. So this replica-like revival has the strange effect of a museum piece in this “new writing” space, posthumous and reverential.

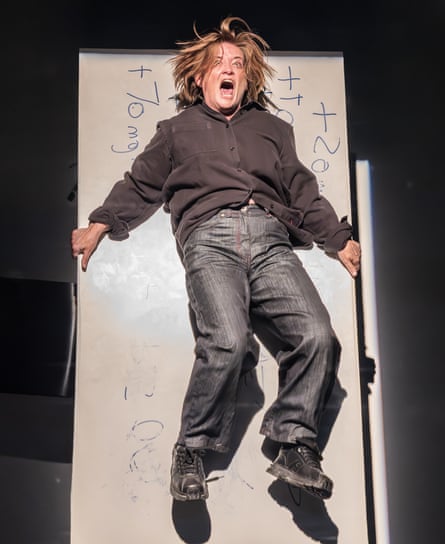

Jeremy Herbert’s set is a white square with functional table, chairs and an overhanging mirror that reflects the audience and the protagonist’s selves which acquire more fractured counterparts in shadow. Light alters in this room, glowing sharp or soporific, like the setting and rising of the sun (beautifully designed lighting by Nigel Edwards). There are bursts of disturbance within, reminiscent of the grey fuzz of an old TV set, which becomes an inspired visual analogy for the dismal brain fog of depression.

The protagonist variously lies prone, circles the stage or sits in antagonistic conversation with a psychiatrist (another inner voice). There are deep, startlingly lyrical passages (“the cold black pond of myself”) alongside bathos and grim humour; the script is an exemplar of Kane’s perceptive and emotionally unswerving gifts as a writer.

But dramatically it is sedate. You wish for something messier, louder, angrier. There are flickers of this – a stunning moment when the protagonist (McInnes) shouts as she lies on the table, enraged at life – yet it then returns to blankness. Maybe this non-mood is the point – a depression that leaves meaningful emotion quashed – but it evokes a kind of vacancy in the air nonetheless.

There is still value in its staging and poignancy, too. It is beautifully performed with moments of bared anguish and delicate detail. The opening of the stage windows, a countervailing gesture to the reflection of a closed window on stage, is a haunting, yet exhilarating, final image.

At the Royal Court theatre, London, until 5 July. Then at the Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon, 10-27 July.

.png) 2 months ago

27

2 months ago

27