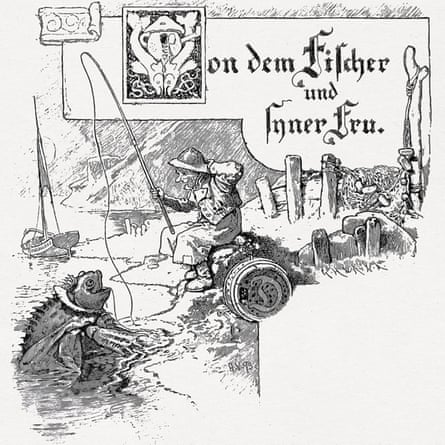

In the German fairytale The Fisherman and His Wife, an old man one day catches a strange fish: a talking flounder. It turns out that an enchanted prince is trapped inside this fish and that it can therefore grant any wish. The man’s wife, Ilsebill, is delighted and wishes for increasingly excessive things. She turns their miserable hut into a castle, but that is not enough; eventually she wants to become the pope and, finally, God. This enrages the elements; the sea turns dark and she is transformed back into her original impoverished state. The moral of the story: don’t wish for anything you’re not entitled to.

Several variations of this classic fairytale motif are known. Sometimes, the wishes are not so much excessive or offensive to the divine order of the world, but simply clumsy or contradictory, such as in Charles Perrault’s The Ridiculous Wishes. Or, as in WW Jacobs’ 1902 horror story The Monkey’s Paw, their wishes unintentionally harm someone who is actually much closer to them than the object of their desire.

Today, of course, most young people grow up with an enchanted fish in their pocket. They can wish for their homework to be done, and the fish will grant their wishes. They can wish to see any kind of sexual act imaginable, and (if they work around regional age-controls with a VPN) it will be visible. Soon they will be able to wish for films on a subject of their choice and these will be generated within seconds. They wish they had already finished that university essay – and lo and behold, it’s written.

This change in approach will not just upend our relationship as consumers of the creative arts, of written, musical or visual content, it will also reconfigure what it means to be creative and, therefore, what it means to be human. I can imagine that most people in the near future will be able to task an AI representative with all kinds of tiresome interactions – negotiating contracts on their behalf or acting as their agent, receiving and cushioning criticism, collating information, surveying opinions and so on. And the sea will never turn dark.

For now, young Ilsebills sitting in university lecture halls can still expect to be fined when their professor, who grew up in a different era, notices that she has got the enchanted fish to write yet another one of her essays. But that will only last a few more years, until Ilsebill is part of a self-confident majority and most of the professors grew up as Ilsebills themselves. Ilsebill wishes for a boyfriend, a spiritual coach, a therapist – and in an instant she will have one. With each one of these companions, it will feel as if Ilsebill has known them for years, which is literally true.

One could accuse Ilsebill of complicating matters when, like her mythical predecessor, she one day actually wants to become pope and immediately does so in her small world. But if anyone can easily become the pope, then the appeal of being the pope disappears for Generation Ilsebill. Because things only become interesting and desirable when they require a certain amount of resistance, or an obstacle, to be overcome. Ilsebill, however, only knows that type of attractive resistance from learning through prompting – through ever more precise wishing.

She devotes most of her energy in life to fine-tuning the tone of her results. She won’t have acquired her own ear for the tone of a piece of writing, but from gauging the way other people or AIs react to a text that she sent she will know whether the content is appropriate or inappropriate. That way, she learns to make ever more credible wishes. In the past, Ilsebill rarely met people who found things that she said interesting or remarkable. But today everything she discusses with her AI is deemed interesting and remarkable. Finally someone is properly listening, in the way no human partner could do so unconditionally.

And what if the point is reached where all the wish fulfilment leaves Ilsebill feeling empty? What paths are still open to her then?

The first is the path to decadence. We know this mechanism from studying very rich people. In the future, those who have enough money will be able to still afford human therapists or visit the cinema to see films made with real humans. Recently, someone on an AI forum suggested that in the future we should simply have some AI produce masses of child sexual abuse images, so that at least no real children would be harmed in their production. This suggestion was instantly ridiculed, because consumers of child abuse images are not buying just any visual stimulus, but primarily the certainty that real children were tortured. They insist on the credible provenance of the product, its “aura”, so to speak. If Ilsebill has enough capital, she will in a way be like them.

The second path is that of small breakaway communities that artificially create difficulties and obstacles for each other, perhaps in the style of old-fashioned sports or hunting clubs, perhaps also in a sect-like manner. They meet in secret or exclusively for an underground event in some basement, which will require them to queue. There’s no goal other than the agonising act of queueing itself. I got this idea from Stanislaw Lem’s novel The Futurological Congress. Today, in 2025, queuing is still free. Later generations might well marvel at this.

after newsletter promotion

The third path is the most likely and the most obvious. Within her fairytale world of wish fulfilment, Ilsebill will discover an overarching principle that colours all her wishes anew, re-weights them, and gives them meaning: guilt. It is well known that guilt is the strongest means of binding a person to a product. A product that one loves but is ashamed to use grows powerfully in the mind and strongly attaches itself to a personality, enveloped in neuroses and real-life substitute virtues to compensate for the ever-increasing guilt.

Ilsebill naturally takes on the enormous ecological guilt of the enormous waste of resources caused by AI. The main guilt is transferred from the giant corporations, the all-pervasive companies, or even the interaction of several states, straight on to Ilsebill, and she now does the logical thing of restricting and punishing herself more and more in the way she goes about her everyday life. Every morning she wakes up with the certainty that every small decision, every smallest wish, will massively damage “the planet”, “the society” or “the future”. She blossoms in her new-found role as saviour, in this system of martyr-like vicarious guilt. This role feels, not without justification, like a battle that will be fought within her for all eternity. It is the magic ingredient that can restore to her life the long-missing flavour of self-sacrifice and inner contradiction. Ilsebill doesn’t protest against the absurd waste of resources, but rather curtails all her freedoms in her private life, such as her supply of adequate nutrients, her water consumption, the number of children she has and her range of movement. In the end she dies, as a kind of Christ of corporations, and takes all her sins to her grave.

The reason why so many European fairytales warned against unwise, ignorant wishes was because like most large, collectively produced complex narratives, their basic theme is individuals coming of age. How does a person grow up, how do they find their place in life, what should they pass on to the next generation, all these questions. Ilsebill, however, at least in this last scenario, no longer has the freedom to answer any of these questions by herself. It will all be decided for her.

-

Clemens J Setz is an Austrian novelist and poet

.png) 1 month ago

41

1 month ago

41