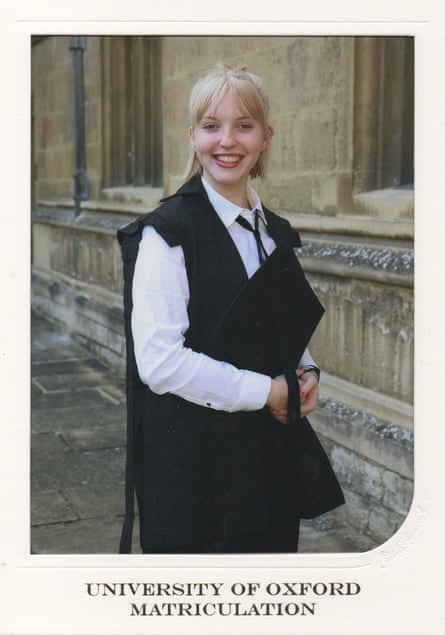

“I am a teenager, living in an age with war, corruption, discrimination, racism, sexism. But no one seems angry about it. People see the slight advances towards equal society as having solved our issues entirely and it just isn’t enough.”

It’s March 2015, and I’ve done it: I’ve solved inequality. Standing in the basement room of Modern Art Oxford for my regional heat of the Articulation prize public speaking competition, I truly believe that I may have just introduced this room full of parents and teachers to the concept of feminism. I’m very pleased with myself.

The Articulation prize is a competition for post-GCSE students, aged 16 to 19, who are given 10 minutes to present on a work of art of their choice. I was told about it by my head of sixth form, whose office I had ended up in just weeks before the competition. As a pupil, I was clever but chatty and easily distracted. I felt everything acutely and was frequently overwhelmed and tearful.

I also took an all-or-nothing approach to my education: either be the best, or don’t bother. In the office, we discussed my decision to drop history AS-level within weeks of starting because I didn’t think it would be possible for me to finish it with an A. “Not everything is death or glory, Verity,” he implored.

Along with my longsuffering art teacher, the head of sixth form recognised that Articulation was exactly the opportunity that I needed – after all, I loved art AS-level, and was suitably gobby as part of the school’s rag-tag debate club. He suggested I prepare something for a preliminary in-school heat. From memory, I don’t think anyone else applied.

I chose to speak about Damien Hirst’s medicine cabinets, which I had seen at his 2012 retrospective at Tate Modern (the poster of which is still stuck on the wall behind my desk). I’d seen Hirst’s work for the first time as a child visiting Ilfracombe, the north Devon town where my grandmother had grown up, and where Hirst had a restaurant, the Quay, full of formaldehyde-imprisoned fish, and wallpaper covered in pills. I loved that his work was funny and contrarian, and that he got away with calling whatever he wanted “art”. I loved that my grandmother hated it. But maybe most of all, I loved that, because the medicine cabinet installations were named after tracks on their 1977 album, I was going to say “Sex” (Pistols) several times during the talk. I truly was the most radical young thinker of my generation.

At the regional heat, there were nine other speakers, all of whom had better historical references, made fewer unqualified, sweeping statements, and used the word “bollocks” less. I was awarded third place. As a teenager who put almost all of her self-worth on achievement, this would usually have been a devastating outcome. But, in that moment, the fact that people seemed to enjoy my talk, and had laughed exactly when I had wanted them to, felt enough.

By the time Articulation invited me to give my talk again, this time as part of a conference at the British Museum, I had sent in my application to read history of art at Oxford. Before the competition, I had thought I was going to apply for English or German, but certainly not at Oxbridge, where I knew I would never be “the best”. But the competition had emboldened me and made me believe that my opinions were worth sharing, even when I didn’t speak the lingo. I didn’t need to be the best: I just needed to put my spin on things.

Talking about art – and finding ways to make people laugh while I do it – quickly became my north star. My Articulation journey came full circle when I was invited back this spring to be the first graduate judge of an Articulation heat.

The competition gave me confidence beyond my degree choice: not that I could achieve great things, but that I didn’t have to. I no longer needed to covet perfection; I needed to lean into my own voice. I went from being anxious and easily overcome – passionate but quick to frustration – to someone who believed in their capabilities. I didn’t need to be perfect. For the first time, authenticity meant more to me than flawlessness.

I’ll always be grateful to the sixth-form head who made the effort to understand me when I was an obstinate and emotional teenager, rather than simply rolling his eyes (and, looking back, I think an eye roll would have been entirely justified). Not everything was death or glory; I learned that it is often worth trying, even without the promise of “winning”.

.png) 1 month ago

36

1 month ago

36