On the main road heading south out of Manchester city centre, the excitement and enthusiasm are tangible. Oxford Road has changed a lot since October 1945. While its grand buildings remain, the wartime bombsites and smog are long gone. Much of Chorlton-on-Medlock, the residential area it bisected has been lost to postwar clearances and replaced by university complexes.

But to the young people gathered in the foyer of the Contact Theatre, the events of 80 years ago were full of relevance. The dance show they came to see – See My World: Homage, staged by the choreographers Joe Price and Kieron Simms a fortnight ago – was just one of an unprecedented number of events to celebrate the anniversary of the fifth Pan-African Congress, which took place less than a mile away at the former town hall.

The congress was a seismic moment for Black countries during their fight for independence from colonial rule and helped to shape the destiny of millions. But for years the event was an under-recognised chapter in Manchester’s radical history, spurring the late community leader Kath Locke, among others, to campaign for a commemorative plaque outside the building in the 1980s.

Now, against a backdrop of increasing unity between African-Caribbean countries, resurgent anti-Black sentiment and increased awareness of the debt Manchester owes to slavery and colonialism, the congress’s message of Black unity as well as political and economic liberation is experiencing a resurgence.

Tunde Adekoya, the artistic director and chief executive of the See My World festival – which celebrates Manchester’s pan-Africanist legacy – has been central to the 80th anniversary celebrations, organising a series of seminars, exhibitions and performances.

Adekoya’s introduction to the congress came 10 years ago and it has inspired his work ever since. “It was a struggle that resonated with mine, and I decided had to look at ways to continue to develop our communities in the same way (as the congress), creating a festival that would allow people to have these conversations, to look at what betterment would [look] like through events and storytelling, reclaiming narratives and looking at how we develop the next generation of leaders,” he said.

While the legacy of the event continues to resonate within Manchester’s arts and activist communities, African and Caribbean politicians are taking steps to fulfil the dreams of the original delegates.

In September, the African Union revealed it was joining forces with Caribbean countries to seek reparations from European colonial powers. The announcement, at the second Caricom-Africa summit in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, came as the regions strengthened their commitment to cooperate on global financial reform, climate action, education, health, trade and cultural exchange.

The Caricom secretary general, Dr Carla Barnett, said the summit was “guided by the pan-African ideals set out by iconic minds from the Caribbean and from Africa, with Marcus Garvey, Patrice Lumumba, George Padmore, Jomo Kenyatta and Kwame Nkrumah among them”.

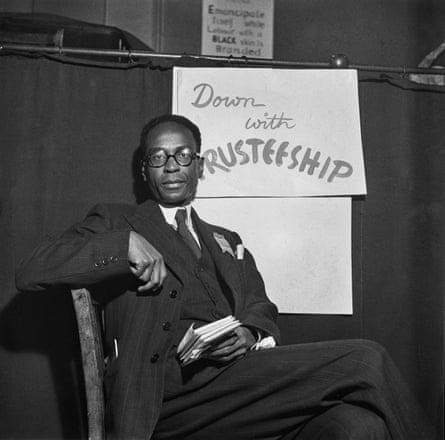

The Jamaican activist Amy Ashwood Garvey, the former wife of the pan-Africanist Marcus Garvey, was a delegate at the 1945 event – which was chaired the African American intellectual William Edward Burghardt Du Bois – alongside Nkrumah, Kenyatta, the Trinidadian journalist Padmore, Dr Hastings Banda, Jaja Wachuku and Obafemi Awolowo.

After independence, Nkrumah, Kenyatta and Banda went on to lead Ghana, Kenya and Malawi, respectively, while Wachuku and Awolowo became statesmen in Nigeria.

Alma La Badie, the Women’s Auxiliary air force veteran who campaigned for the rights of Black women and children in the UK, and Len Johnson, the trade unionist and boxer of mixed heritage who grew up in working-class Clayton, east Manchester, were among those who represented Black Britain at the congress.

Dr Shirin Hirsch, a historian at Manchester Metropolitan University (MMU) and at the People’s History Museum, said: “The congress was electric, hosting 200 attendants with 87 delegates representing 50 organisations from across the world. Many delegates would return to Africa newly inspired as part of a network of pan-Africanists.

“The hall itself was grand, with handmade posters … calling for oppressed people of the world to unite; ‘freedom for all subject people’ was another demand. Karl Marx was quoted – ‘Labour in the white skin can never free itself as long as labour in the black skin is branded’ – and there was a call for ‘Arab and Jews to unite against British imperialism’.

“For Manchester’s Black delegates and observers to the congress, we know it was a hugely important event too, with attenders like Len Johnson continuing to organise against racism for decades after.”

after newsletter promotion

Ntombizodwa “Zodwa” Nyoni, a writer and lecturer at MMU, played a critical role in building excitement around the anniversary celebrations via her hit play based on the congress, Liberation, shown at the Royal Exchange theatre. She was keen to highlight crucial messages from the pan-Africanism of 1945 for an audience in 2025.

“A lot of [the delegates’ concerns] around being anti-racist and thinking about freedom of the press, thinking about all the rights of women – all of those things are really relevant to where we’re at today,” she said in an interview for a bonus episode of the Guardian’s Cotton Capital podcast.

“Today, when we think [about our] activism, a lot of it is happening online. So there’s something specific and … special about what happens when a group of people meet and they say: ‘We are going to sit together and plan change.’”

From debates to concerts and exhibitions to literary readings, several institutions in Greater Manchester – including MMU, the Ahmed Iqbal Ullah Race Centre, the Caribbean and African Health Network and the flagship arts venue Factory International – have staged events centred on the Black diaspora that have climaxed in the anniversary month of October, which is also Black History Month in the UK. In Moss Side and Hulme, historical centres of postwar Black life in Manchester, the political festival The World Transformed brought pan-African activists together, adding to the city’s rich legacy of Black activism.

The historian Hirsch added: “Manchester during the second world war had this thriving Black community that had settled here before the [Empire] Windrush ship and a later generation joined them.

“Within this community was a very active pan-Africanist network. In fact, the British state had pinpointed Manchester as the centre of the pan-Africanists during the war. The Negro Association in Manchester was a key network, established in 1943 by Dr Peter Milliard, that provided the basis for the Manchester branch of the Pan-African Federation.

“It actively encouraged solidarity with anticolonial struggles, for example: raising money in support of the Nigerian general strike in 1945. On the Negro Association membership lists – on show at the People’s History Museum – there are very famous names like Jomo Kenyatta, future president of Kenya, who lived and worked in Manchester for a short time, but there are also many local Black Mancunian members that we still know very little about.

“The central pan-Africanist in Manchester was T Ras Makonnen, who was the real force behind the congress taking place in Manchester. Makonnen set up a whole range of restaurants, bookshops and even a tea shop around the Oxford Road that were able to attract a huge audience because they did not operate a colour bar and welcomed Black GIs and other racialised communities.

“From these ventures, Makonnen was able to finance the congress. His links with the local Labour party, [which] had political control of the city, meant they could secure the large Chorlton-on-Medlock town hall (now an MMU building) as the venue for the congress.

“It is hard, from these media reports, to get a sense of the exhilaration and sense of freedom that Black people must have felt meeting and organising in Manchester. Walking into the town hall for the congress, with the flags of Black nations on display, there must have been a feeling of pride and determination to continue the struggle.”

This pride and determination is still felt today. Edna, who came out on a chilly October night to see Homage at the Contact Theatre, said: “I was born in Portugal but my origins are from São Tomé and Príncipe. Believing in pan-Africanism means believing in yourself, claiming who you are and always fighting for what matters.”

.png) 3 months ago

79

3 months ago

79