The signature at the bottom of the email about witnessing an execution said cheerfully: “Oklahoma Corrections. We Change Lives!”

I had received the email three weeks earlier. It explained that I was being invited to participate in a lottery, from which five media representatives would be selected to witness the execution of Tremane Wood in the Oklahoma state penitentiary on 13 November. I had never heard of Wood, who had been convicted of the murder of Ronnie Wipf, 19, in 2002.

For more than 20 years Wood had been sitting in prison, mostly in solitary confinement. He and his brother Jake, with the help two female friends, had plotted to lure Wipf and a friend, whom they’d met at the Bricktown Brewery in Oklahoma City, to a motel room in order to rob them. But Wipf ended up murdered, with a knife stuck five inches into him.

Now, 22 years later, on my computer screen, I watched Kay Thompson, the Oklahoma department of corrections press officer, in a fluorescent-lit office, holding up a small box. Inside were pieces of paper with names on them.

My heart was beating. A lottery? So this is how audiences are invited to watch executions in the age of the internet? I had put my name forward as a witness a long time ago, having done some reporting on the death penalty and now keen to learn more about the controversial drugs used in the process – but I was still half-hoping I would not have to actually witness a killing.

Thompson pulled my name out of the box. I shut out the voices telling me this could be more disturbing than anything I’d seen in many years of reporting, and I set to work contacting Wood’s friends, his lawyer, his family and the family of the murder victim, Ronnie Wipf.

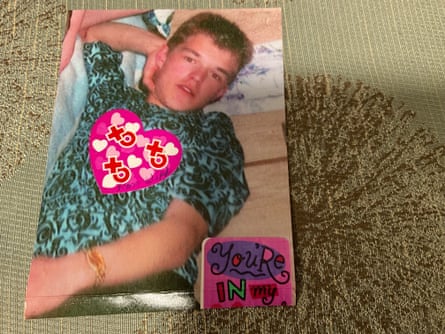

Within days, his friends were forwarding me emails from Wood in prison; I spoke to his mother, Linda, almost daily. Slowly, a picture emerged of a man who joined a robbery gone wrong – a man influenced heavily by his aggressive, angry and violent big brother, Jake, who had testified that it was he who committed the murder, not his little brother.

Jake, who had good lawyers, got life in prison. Tremane, represented in his trial by a lawyer who abused alcohol and cocaine, and who barely built a case for him, got death. After he was sentenced, his lawyer handed him a business card. “I’m sorry,” it said. “You got me at a bad time.”

Wood got new lawyers, and went through many appeals. His case went all the way to the US supreme court and as the execution approached it was still unknown whether the justices would halt it, or allow it to go ahead.

A week before execution day, a close friend texted me: “Don’t go. It’s horrific.”

I promptly deleted her text and booked my flight to Oklahoma, but inside I was nauseated. I didn’t know how I would handle it. I remembered my grandfather, a crime reporter in Texas in the 1930s, telling me he had seen nine men executed in the electric chair before he was 20. I figured if he could bear witness, I could.

The night before the scheduled execution, in Oklahoma City, I met Linda in a church where friends had gathered for a vigil. She had just come from her final visit with her son, and looked pale and exhausted. As a young woman she had been horrifically abused by her husband, Tremane’s father, and she had already lost one son when Jake killed himself in prison 2019. Now she was about to lose Tremane.

She sat on a faded red chair, slow tears dripping. The supreme court ruling had still not come down. “The waiting is excruciating,” she said, clenching her jaw. “Excruciating.”

She read me a note Wood had written about 10 days before.

“I am not a killer,” he wrote, adding that he hoped his case would bring some kind of change.

Linda said she wasn’t going to witness the execution. She tried to persuade Tremane’s son, 27-year-old Brendan Wood, not to go either. “I told him: ‘If you see your Daddy take his last breath, you will never be able to unsee it.’”

Tremane, too, had asked Brendan not to attend.

“He didn’t want any of us to be here,” he said. “He wanted people to remember him for who he actually was.”

But Brendan, a US army infantryman stationed at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, was going. He had made his own decision that it would be more terrible to leave his father to die alone, surrounded by nothing but white walls and executioners.

“I was like, all right, if I was on my deathbed in the hospital, what would I want?” he added. “I would love to be surrounded by family … I would love to know that people love me and I’m here and that I was cared for.”

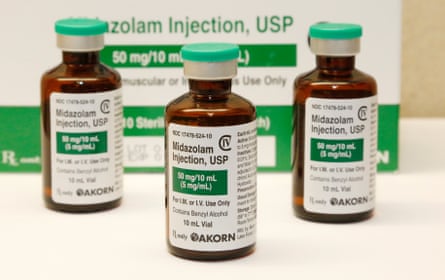

Racing down the empty highway in the dark of the following morning, after waking at 4.30am to drive the two hours to McAlester, Oklahoma, I wondered what it would be like to see a man being killed at close range. Earlier I had talked to Dr Craig Stevens, a professor of pharmacology at the University of Oklahoma, about the drugs they would use to kill Wood.

Stevens said there was a high chance of pain. He explained that Wood was to be injected with midazolam, which is a sedative, not a true anesthetic. Other states simply manufacture pentobarbital, a drug that fully anesthetizes condemned prisoners, he said. “Texas, which executes the most prisoners, they just make it themselves, and other states make it, so it’s available to make and do it yourself. You can get it from apothecary-type compounding pharmacies,” he said. But not in Oklahoma.

Then Wood would receive a paralytic, which would leave him unable to scream or move, followed by a drug-induced cardiac arrest – effectively a fire bolt to the heart. Would I see a man lurch, vomiting or gasping as others have with these execution drugs? I tried to block the thought.

Procedurally, at least, I knew roughly what to expect as a witness. No cameras or digital devices were allowed. We’d sit in a room with members of Wood’s family and officials, behind a curtained window looking into the execution chamber.

The curtain would be raised. Wood would be strapped to a gurney. An IV would be inserted. The drugs would soon follow. He would be asked for his last words. He would be killed. His body would be put in a body bag and taken out.

As I approached McAlester, I saw the prison rise up – a sprawling white fortress, built in 1909 and encased in razor wire. Inside, I knew, Wood had been on death watch – placed in a transparent cell, located directly next to the execution chamber, where his every move was monitored and communications with his family were cut off. In another note, Wood had written about losing contact with his family: “They are the only thing that stop me from going over the edge.”

On the prison grounds I was ushered into a press room. Thompson, the official who had pulled my name out of the hat, was there. So were some other local Oklahoma journalists who had attended previous executions. They seemed used to it. One was joking about how the quality of the snacks had deteriorated. “Where are our frosted buns?” he asked.

I very rarely get headaches, but now I had a raging one. It was now 9.20am – 40 minutes until the execution – and we had still not heard from the supreme court, nor from Oklahoma’s governor, a Republican supporter of the death penalty. Either could stop the execution, but Thompson explained that if there was no word by 10am, Wood would be killed as planned. She kept running out of the room on urgent calls.

Then I received the news on my laptop: the supreme court had denied clemency.

This is it, I thought. Thompson’s going to come back in and take us to the execution chamber.

Thirteen minutes remained until Wood would be put to death. A colleague who was with Brendan Wood in another building on the prison grounds, where no one knew what was happening either, sent me a text: “Such a sick spectacle.”

By 9.58am, there was still no word. I was trying to imagine what Linda was going through, probably sitting on her big old soft chair in her small house two hours away, with Andre, Tremane’s brother, in pieces inside, but there and trying to be strong for his mother.

And what of Tremane? Had they strapped him down yet? It seemed inevitable now that he would be put to death.

I tried to steel myself for the medieval spectacle. I felt nauseous. I thought about the people who’d watched hangings throughout history. I thought about the Romans. I thought about the governor, like a king in his palace, with the power to decide if a man lived or died, courts be damned. The one thing I tried not to think about was the execution.

It was 9.59am. Thompson returned and took another call. Again, it looked urgent.

Why weren’t we on the bus yet to the execution chamber viewing area? Why weren’t we in the room already?

Had the governor been given pause by the fact that even the family of Ronnie Wipf, the murder victim, said they did not want the execution to go ahead?

“Clemency,” Thompson blurted out. “Clemency.”

A lightness entered my whole being, as though a terrifying beast, there to bring nightmares, had just left the room and vanished.

There would be no execution. After 20 years of litigation, Tremane Wood’s death sentence had been commuted to life in prison without parole.

One of the first things the local journalists wanted to know was what Wood had for his last meal. “Well, he didn’t eat everything,” Thompson said, in a singsong voice suggesting she had done this many times. “Catfish. He had one piece of fish. He had a third of the okra. He had the ice-cream.” There must be a regular “last meal” menu, I thought.

She told us to leave so the prison could return to normal operations. Staff began dismantling the press conference podium.

Outside, I met Brendan. He had driven 18 hours from his base in North Carolina to watch his father die.

“I said goodbye to him yesterday,” he said, sitting in my car, bolt upright, his voice cracking and tears streaming down his face. He was shocked the authorities would wait until the very minute of the execution to announce it was off. “I think it’s cruel and inhumane,” he said. “It’s torture.”

Later we would learn that 30 minutes before he was scheduled to die, Tremane Wood was put into a holding cell. His lawyer, Amanda Bass-Castro Alves, was allowed in to see him. “He had mentally worked himself up to face the end, to go in there and be strapped to the table and executed,” she said.

When, very close to the minute of execution itself, he was told that he would not be killed, “he just collapsed on to the floor, just literally collapsed”, she said. “The pressure that he was under being lifted just took everything out of him.”

Later that night, in his cell, he would collapse again, falling off the bed and injuring himself, apparently through dehydration and stress. He hadn’t eaten since his last meal.

Why, I was left wondering, did the governor wait to announce clemency until 10am exactly – literally the last minute before Wood’s execution?

The voice of a lawyer I had spoken to the day before rang in my ears. Wayna Tyner, who represented Wood’s brother in his trial, was replying to my question about why Oklahoma doesn’t bother to make the drugs that actually anesthetize death row prisoners, like other states do, to ensure executions don’t cause extreme pain.

“Because they don’t give a shit,” she said.

.png) 2 hours ago

6

2 hours ago

6