By now, September 2025, a certain formula has solidified on Broadway: stage a familiar-ish play, cast well-known film and TV actors, set a limited run and tickets will hopefully sell, or at least command high prices. It’s a commercially strong bet – while most Broadway musicals are failing financially, six plays have already become profitable: Oh, Mary! (starring Cole Escola), All In: Comedy About Love (John Mulaney, Jimmy Fallon, et al) Romeo + Juliet (Kit Connor and Rachel Zegler), Othello (Denzel Washington and Jake Gyllenhaal), Glengarry Glen Ross (Bob Odenkirk, Kieran Culkin and Bill Burr) and Good Night, and Good Luck (George Clooney).

It’s led to some grousing – about ticket prices, about a Hollywood invasion, about the spirit of Broadway. I’m generally agnostic on this – Broadway has always run on star wattage, and screen actors certainly provide some – but it does change how audiences interact with the material. People enter the theater with preconceived notions, certain expectations or, in the case of John Krasinski’s solo show Angry Alan, the specter of one very beloved sitcom character. Actors and directors can work with it, subvert it, challenge it, submit to it, but the celebrity factor won’t disappear. There’s no such thing as a blank canvas.

Tell that to Marc (Bobby Cannavale), a middle-aged man deeply troubled by his friend’s purchase of an all-white painting in Art, the latest limited-run, starry revival to open on Broadway. Serge (Neil Patrick Harris) sees lines, shadows, depth within the 4ft x 5ft canvas. Marc stares very hard, tries different angles – Cannavale, a two-time Tony nominee, wrings laughs out of this silent effort – but sees nothing but offensive folly in his friend’s $300,000 purchase. Their mutual friend Yvan (James Corden), less professionally successful but more open-hearted, sees whatever is needed to keep his friends agreeable.

Yasmina Reza’s French-language play, first staged in Paris in 1994, then Broadway in 1998, is a study of male friendship. Which means that these three longtime friends – 25 years of friendship, we’re told – spend an inordinate amount of time talking about a painting that, at least to a viewer at the Music Box Theatre, appears as a large white rectangle. (Harris’s plaintive Serge, speaking directly to the audience, insists: it is not white!) This would grate – it skirts the edge of wearisome – if not for three solid performances and the timeless insight of Reza’s script, translated here by Christopher Hampton, into men’s coded language of feeling.

Indirectness, of course, knows no sex or gender. But part of the magic of Reza’s play, staged here by Scott Ellis (most recently the director of Doubt), is the seamless demonstration of the lengths men will go to avoid speaking emotions plainly, the delicacy with which she writes specifically, identifiably male versions of passive aggression and avoidance. In a tight and uninterrupted 90 minutes set in one apartment – Ellis keeps the setting somewhere in Paris, though David Rockwell’s set evokes antiseptic luxury Brooklyn high-rise – the three actors capably ride a friendship devolution through some moderately entertaining shouting matches and quieter, cutting confessions.

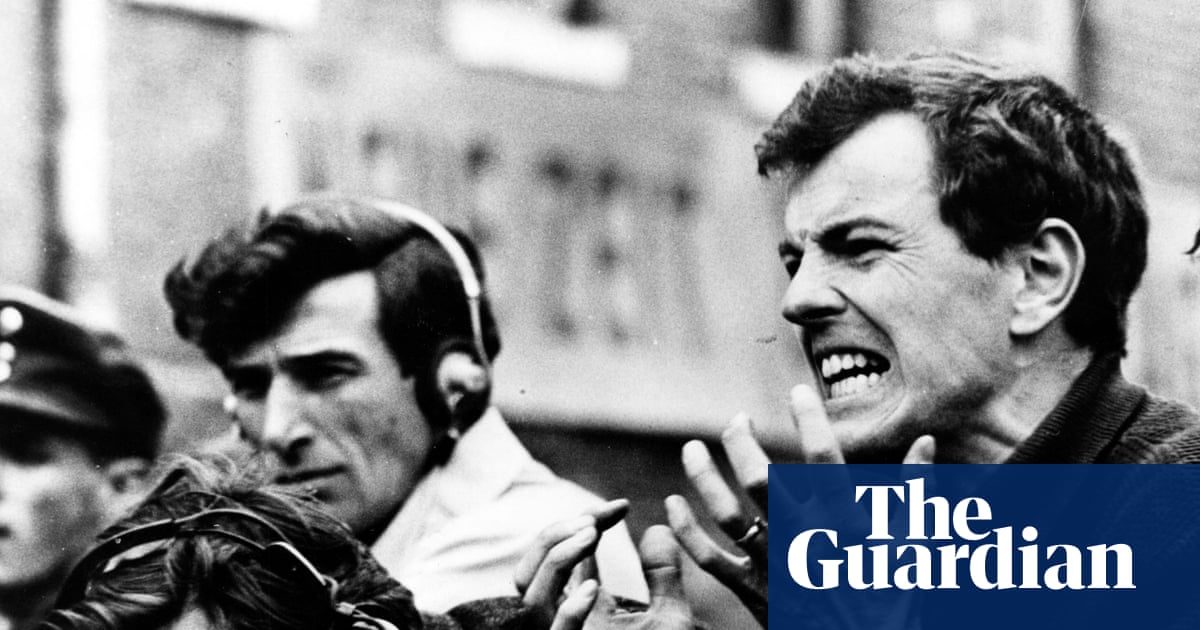

Harris and Cannavale make light work of these two politely adversarial aesthetes – the former crisp and tightly wound, the latter swaggering and easily wounded, both a little detestable. But it’s Corden, returning to Broadway for the first time since winning a Tony in 2012 for One Man, Two Guvnors), who steals the show, in a bit of stage image rehab post-Carpool Karaoke and, for the chronically online, Balthazar ban. As both the heart and the court jester for the show, Corden is superb, a perfectly calibrated level of hysterical, sincere and crisp. One blistering monologue sees him ranting, in the voice of three separate characters, for several minutes straight without missing a beat; it was not celebrity compelling the extended applause when he finally collapsed, spent and spittle-covered, into a chair.

You can only talk art for so long. All three characters eventually crack open, though not, perhaps, to the degree one would hope, as Serge and Marc still rely on abstractions of taste, influence, ideas. It’s when Yvan crumbles, tearfully admitting the significance of these friends in this life, that the production unlocks some prismatic, elusive sentiment, a color noticeably missing from the canvas. Or maybe that’s just my reading, colored by many a frustrating attempt to pull emotions out of a man. Ultimately with any play, just as painting, you supply your own background and see what you see.

.png) 1 month ago

44

1 month ago

44