‘Knowing there might be an alternative brings relief and hope’

When she was only 18, a few months into an undergraduate degree in classics at Warwick University, Maddie Cowey was diagnosed with a rare cancer called sarcoma. She had gone to the GP about a lump on her shoulder that had been growing for 18 months. Soon after, she learned that the cancer had spread and was incurable.

As there are no approved treatments in this country for Cowey’s type of cancer, it has been managed so far through a mix of clinical trials and compassionate-use (individual, rather than group trial) drugs. “The cancer is not completely stable,” she says. “The aim is to slow it down. If it shrinks, that’s great.” Now, aged 27, she isn’t experiencing any symptoms from the cancer itself. “I’m in reasonably good health. Most of the issues I’ve had have been side-effects from the treatment.

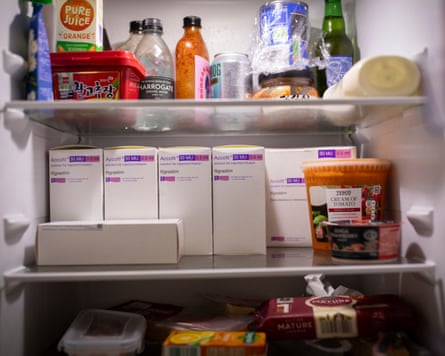

-

Cowey photographed with her parents Jane and Colin (above) and at home taking her medications (top left), some of which is stored in her fridge

“I’ve definitely had times where I feel like my young adult years have been taken away from me and I felt more bitter about it,” Cowey says. “I’ve had to process a lot of different things, but I’m in quite a good space now, where I feel accepting of it.” She has just returned from a two-week trip to visit her sister in Vietnam and currently works four days a week for a disabled persons’ charity.

“I know the biggest opponents to assisted dying are the disability rights activists,” Cowey says. “As someone living with a life-limiting health condition who will have to rely on the state at some point, I completely get the perspective of a disabled person. But the assisted dying bill is specifically for dying people.

“Cancer can be so uncertain, especially when it spreads to your organs, and you don’t know which one it’s going to decide to destroy and how painful it’s going to be,” she says. “Knowing there might be an alternative brings a lot of relief and hope. We deserve the right at the end of life to say how it’s going to go.”

‘I’m not giving up – I’m facing reality’

-

Miranda Ashitey, photographed by South Norwood Lake, south London

Miranda Ashitey died of metastatic breast cancer on 26 June, less than three weeks after her 43rd birthday. A former administrator and VW camper van driver, she is seen here in South Norwood Lake in south London, close to where she lived.

Ashitey was first diagnosed with stage two breast cancer in 2014. She went into remission for about three years before learning that the cancer had spread in February 2019. “What I thought was a seasonal cold lasted a long time, so I eventually went to the doctor,” she later recalled. “They said I had a chest infection, to take some antibiotics, it’ll be fine. It wasn’t fine.”

Throughout her illness, Ashitey campaigned to raise awareness and improve treatment for those with secondary breast cancer, focusing in particular on the experiences of Black and LGBTQ+ people. Fundraising efforts for cancer charities included the Great North Run, which she completed five times, and a skydive in 2022.

-

Ashitey’s bag with a badge saying she is shielding (above left) and her walking stick with its pink ribbon (above right)

On assisted dying, Ashitey said she could “see both parts”, especially why disabled people might “feel under more pressure to make a decision that might not be in their interest”. Coming from a west African background also made discussing the possibility of an assisted death with some members of her family “a bit difficult”.

“But then people need to be able to have that choice if they want to end their lives,” she said. “It’s like I’m saying, ‘I’m giving up’ – but I’m not giving up: I’m facing reality. Being matter-of-fact rather than emotional is how I deal with things, and how this should be dealt with.”

‘Discussing my potential death so publicly over the last 18 months has been intense’

-

Sophie Blake, 52 (in pink), with her mother Christine (left), daughter Maya (second right) and sister Lucy (right)

“I have a family with a lot of cancer in it, and I’ve known people to suffer as they die since I was a teenager,” says Sophie Blake, 52, a former TV presenter and prominent campaigner for assisted dying. “So I’ve always 100% believed in the right to choose. When I was diagnosed myself, it seemed natural to help campaign for it, whether it happens in my lifetime or not.”

Blake, who lives in Brighton with her 18-year-old daughter Maya, received her initial primary breast cancer diagnosis in December 2020. Despite her family history, she was mistakenly told that she had a low risk of recurrence. But as soon as she finished treatment, she started feeling unwell. In May 2022, Blake learned the cancer had metastasised – to her lungs, liver, pelvic bone and abdominal lymph node. There was also new cancer on the skin where she’d had her lumpectomy.

While the cancer is incurable, Blake has responded well to treatment and there is currently no evidence of active disease in her body – though the drug holding it at bay comes with challenging side-effects, including fatigue, cornea damage and bone and joint problems. But she’s happy to put up with all of it to stay alive: to keep “making memories with friends and family, travelling, adventures, being a mum”.

Blake recognises the “irony” of this focus on extending life alongside campaigning for “the right to have a peaceful and dignified death”. But she required multiple surgeries after Maya’s birth, and learned then that she is allergic to opioid painkillers. “They couldn’t manage my pain properly,” she recalls. “It was awful.”

The idea of going through a “potentially excruciating death” with unrelieved pain terrifies Blake but, even more, she doesn’t want her daughter to see her in that state. “I don’t want that to be her final memory of me,” she says. Last year, Maya, who is studying music performance at college in Brighton, joined her mother in campaigning for the assisted dying bill. “If more people who were against it read up on it,” Maya says, “they wouldn’t be against it as much.”

-

Blake with her daughter at home in Brighton (top) and some of the supplements she takes alongside her cancer medication (above)

Mother and daughter were in the House of Commons, along with Blake’s mother and sister, when MPs passed the bill in June. “The relief was overwhelming,” Blake says. “Campaigning and discussing my potential death so publicly over the last 18 months has been an intense process, and I was so worried it would have all been for nothing. When the result was read out, I burst out crying – which isn’t like me at all.”

‘She was determined to stay alive – then the treatment stopped working’

-

Richard Tingey and his daughter Heidi photographed near his wife Barbara’s woodland burial grave in Suffolk

Barbara Tingey died of bowel cancer at the age of 76, in July 2023. She was diagnosed two years earlier, six months after her daughter Heidi’s husband John had died of the same disease. A former deputy headteacher at a secondary school in Norfolk, Tingey had taught chemistry since the 1960s. After taking early retirement, she and her husband Richard went on holidays, mostly to France, and spent time with family: Heidi, their other daughter Katie, and their three grandchildren.

“She was so determined to stay alive and beat the odds,” Heidi says. Her mother had three rounds of chemotherapy – “Then the treatment stopped working.” From early 2023, her condition deteriorated rapidly. Although her family didn’t know it at the time, Tingey decided to stockpile pain medication.

-

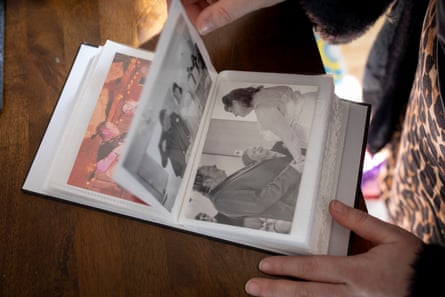

Richard and Barbara are pictured on their wedding day in 1976

“She didn’t talk about the pain much, because she was trying to not draw attention to the fact she was stockpiling morphine,” Heidi says. But Richard recalls “months of sheer agony”, despite good palliative care. At the beginning of July, she attempted to overdose. She was transferred to a hospice and died just over a week later.

“I think Mum did what she did because she was suffering and she couldn’t control when she was going to die,” Heidi says. The experience has convinced Richard to support the right to an assisted death “with safeguards in place … I don’t want my two daughters to suffer what we went through with Barbara,” he says.

‘He would be horrified to know I have PTSD from seeing him die’

-

Lucy Davenport and her son Joss photographed on the seafront in Scarborough

Lucy Davenport’s husband Tom, a musician and music teacher in Scarborough, died of complications caused by bile duct cancer in August 2023 at the age of 48. He received his diagnosis just a year earlier – the first sign was the whites of his eyes turning yellow – and was given 11-12 months to live.

Throughout Davenport’s illness, the couple discussed whether Lucy should help him die “if he got to the point where it was too much”. But they knew she couldn’t risk being arrested and leaving their son Joss, now 10, alone. Lucy recalls that at one stage her husband asked a doctor “for something to just make him go to sleep so he didn’t wake up again. The doctor’s response was, ‘Not unless you grow another two legs and a tail’ – a really blunt statement that I think sums the situation up,” says Lucy.

“That year that we had together we really did it well. We went to Disneyland. Tom and Joss saw Kiss and met them.” They organised a fundraising gig with performances by many of Davenport’s students, friends and bandmates past and present. “It was beautiful – like a living wake.”

And in June 2023, the couple – who had met on a dating site 10 years earlier – had a surprise wedding (people thought they were going to Lucy’s 40th birthday party).

-

Lucy Davenport looks through her and Tom’s wedding album (top left); Tom’s ashes (top right); Lucy and Joss (above)

During his second round of chemotherapy, Davenport became too ill to continue. In hospice, he was made as comfortable as possible. But the cancer had spread to his bowels, causing an obstruction that resulted in faecal vomiting for five hours. Eventually he choked and died.

“It was very, very traumatic. I have PTSD,” Lucy says. “He would be horrified that we went through that.”

Lucy and Joss now live with her friend Alice, whom she met many years ago through Davenport. She continues to feel his presence. “He’s definitely still around. I was listening to a playlist, really silly pop stuff. Then Working Man by Rush came on – one of Tom’s favourite bands. So I just went, ‘All right, I’ll leave it on for you.’”

‘A change in the law would bring the greatest comfort as I try to settle into my last weeks’

-

Nathaniel Dye in Hainault forest preparing to run the 2025 London Marathon

Nathaniel Dye , a 39-year-old music teacher living in Essex, started running about a decade ago with what he calls “the zeal of a late convert”. With hindsight, the first sign that there was something wrong with his health was probably a “small deterioration in training”. In October 2022, he was diagnosed with stage four bowel cancer. Soon it was discovered to have spread to his lymph nodes. The five-year survival odds were 10%.

In the face of this prognosis, Dye set about cramming as much life in as possible. A year after his diagnosis, he completed a 100-mile run from Essex to London – possibly the farthest distance anyone has undertaken with a stoma. In April 2024, he did the London marathon while playing the trombone, and that summer embarked on a 60-day, 1,200km walk from John O’Groats in Scotland to Land’s End in Cornwall. “It just feels like the biggest gift that my body let me do that,” Dye says.

In February, with mounting health issues, he was told he probably had one year to live. “This may well be my last July. Try getting your head around that,” he says. He saw running the London marathon this past April as a “last chance” and completed it in just under eight hours (although, as a former ultramarathon runner, he admits he “found it difficult to accept any praise for the achievement”). Since diagnosis, Dye has also raised more than £40,000 (and counting) for Macmillan Cancer Support, receiving an MBE at the end of last year for his efforts.

Less than a month after the marathon, Dye was taken to hospital with a near-fatal pulmonary embolism. He is less and less mobile, which, “as someone formerly so active, is very hard to deal with”, and has decided to take early retirement this summer, after being signed off work sick for most of the past two years. He hopes soon to be able to go on a long-discussed canal holiday with a small group of friends. “It’s just a case of constantly reassessing expectations based on what my body can do and getting the most out of every day, week, month, whatever timescale it is.”

It’s important for Dye to emphasise how much he wants to keep living while also supporting assisted dying. “The notion of ‘assisted suicide’ really, really gets to me, because if there’s anything I’m not, it’s suicidal,” he says. He has in the past struggled with suicidal ideation but since getting his diagnosis “it’s been the total opposite … That intent to keep going is not, for me, mutually exclusive with the concept of assisted dying at the point where there isn’t any light at the end of the tunnel.”

-

Dye and his brother Jon running this year’s London Marathon (top) and receiving his MBE at Windsor Castle in March

In written evidence submitted to parliament, Dye described the passage of the assisted dying bill as his “dying wish”. Now, he says, he “won’t quite believe it’s real until it becomes law. I don’t speak for all dying people, but I know a change in the law would bring me the greatest comfort as I try to settle into my last weeks and months.”

‘The end of my life is going to matter to me as much as the rest of it’

-

Josh Cook photographed at home in Huddersfield

“I grew up knowing I was at risk of Huntington’s and that my mum had it,” says Josh Cook, a 34-year-old rugby coach from Huddersfield. Children have a 50/50 chance of inheriting the gene that causes the fatal neurodegenerative disorder. The disease – which shares symptoms with Parkinson’s, dementia and ALS – goes back generations in Cook’s family. At 18, he learned he had the gene, too. “We’ve just been unlucky at every coin toss, but I’m not going to have children, so it will stop there,” he says.

Cook’s mum, Lisa, took her own life last year at the age of 57. Her symptoms had begun several years earlier: slurring of speech, involuntary muscle movements, loss of balance. The prognosis was unpredictable; patients usually live for 10-30 years after symptom onset.

“I knew she would never go through with the illness,” Cook says. “My mum watched my great-grandma go through every stage of it at home. One thing that sticks with me was that Mum saw her wear a hole through the carpet in front of her chair from twitching her legs. My mum didn’t want that for herself.”

-

Cook with his mum at a wedding in 1993 (above, top right) and after she gained her degree from the University of London (above, right bottom). His mum had long been a campaigner for assisted dying – she is seen (above left, back right) delivering a petition to No 10 with others in 2002

Cook, who so far hasn’t had any symptoms, believes he would make the same decision as his mother. That’s why a change in the law is so important to him: “So that people can stop the generational trauma.” He wouldn’t qualify for assisted dying under the law currently being proposed, as in the final stages of Huntington’s mental competency is affected. But he is hopeful that the law would give people with this disease a basis to go to court and express their wishes in advance.

“We are still afraid of death in this country,” he says. “For a very small group of us, this is something we think about because we have to. The end of my life is going to matter to me as much as the rest of it.”

‘They wanted to die in a dignified way’

-

Mick Murray and Carol Taylor photographed in the Peak District close to the wall where their friend Bob Cole first noticed he was out of breath walking uphill – which was unusual as he was a mountaineer

A married couple living in Derbyshire, Mick Murray and Carol Taylor have spent the past decade campaigning for assisted dying in memory of their longtime friends, husband and wife Bob Cole and Ann Hall.

In 2013 Hall, a social worker and activist, was diagnosed with a rare terminal neurological condition called progressive supranuclear palsy. Quickly deteriorating, she decided to travel to Dignitas while she was still able in February 2014 – she was 68. Just over a year later Cole, a former town councillor, learned he had mesothelioma, an aggressive form of lung cancer likely caused by him working with asbestos as an apprentice carpenter in his teens. In August 2015, he, too, made the journey to Dignitas, aged 68.

“They actually had a choice over the way that they died, and they wanted to die in a way that was dignified,” says Taylor. Murray adds: “The opponents call it assisted suicide. But the root of suicide is loneliness, despair and depression. This is due to illness. It was almost life-affirming, being there for the actual event. It was really sad, but it certainly wasn’t suicide.”

-

The Sun’s coverage of Cole’s death at Dignitas in 2015, which he had invited the newspaper to report on. He was 68

But Murray and Taylor are adamant people shouldn’t have to go to Dignitas. “Bob and Ann didn’t have any children. They didn’t have any parents alive. When you’ve got family, making that decision, to go and die before you need to, is more difficult,” says Taylor. And beside the often-prohibitive cost, there are bureaucratic challenges, because medical services don’t always cooperate in providing the necessary records. “No ill person could navigate this system, so other people have to navigate it for them. And in so doing, you become complicit,” says Murray.

On the prospect of the law changing in the not-too-distant future, Taylor says: “It’s got to be time, hasn’t it?”

‘He had a full life and was fearless’

-

Pauline McLeod, photographed at her home near York

“He was very anxious about what was going to happen to him,” says Pauline McLeod, whose husband, Ian, died of motor neurone disease at the age of 76 in 2023. Life expectancy for someone with MND sufferer is typically one to five years – McLeod had been diagnosed two years earlier. Over the course of the disease, McLeod lost his mobility and his speech and experienced difficulties with swallowing and breathing. “Not having control was terrifying for him,” Pauline says.

Pauline is pictured here in the home she and Ian, a management consultant, shared in North Yorkshire. But they spent a lot of time travelling as well – to Singapore, Indonesia, Australia. “He had a very, very full life: travelled a lot, liked fast cars and was pretty fearless, really,” Pauline recalls.

“And then the diagnosis was just so devastating – he couldn’t cope with the restrictions that brought for him. He knew that all he had to look forward to was a steady decline.” McLeod would wake up at night with panic attacks that required sedation. An especially difficult milestone was selling their collection of classic cars. “I caught him in the garage crying. They were his passion; he lost everything he cared about,” says Pauline.

-

Photographs taken by McLeod (top) and a small replica Ferrari given to him (above) – he was obsessed with collecting cars but sold them before he died

In June 2022, McLeod attempted to take his own life. Eventually, after he stopped eating and drinking, he was admitted to a hospice where he could die peacefully. “We were very lucky that they took him, because it’s not the same everywhere,” Pauline says. The prospect of legalised assisted dying would, she thinks, be a form of “closure … nobody else has to go through what Ian and I had to go through”.

‘His death was a lonely, dangerous one’

-

Anil Douglas, photographed in Golders Hill park, Golders Green, London, where he used to visit with his father

Anil is the son of Ian Douglas, who took his own life in February 2019, the day before his 60th birthday. Douglas was suffering from secondary progressive multiple sclerosis, having been diagnosed with the neurodegenerative disease in the 1980s. While MS is incurable, it is not usually considered a terminal illness. However, Douglas’s GP had confirmed that his condition was terminal due to the progressive weakening of his immune system. Largely paralysed and in increasing pain, he decided to end his own life while he was still physically able. In a letter to be read at his funeral, he wrote, “This was not a cry for help, and I end my life not distraught or depressed, but as happy as I can be in the circumstances.”

However, the circumstances of his death were “deeply traumatic”, says Anil, who found his father as he was dying. “Nothing can prepare you for that experience of grief in real time, like watching a car crash unfold before your eyes.” It later became apparent that Douglas had already made two attempts on his life in the previous weeks. “His death was a really lonely, dangerous one. He obviously couldn’t tell any of us about his decision.”

-

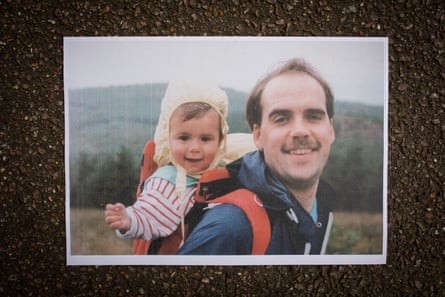

Anil as a baby with his dad Ian (top); with his sister Anjali, 34 (above), on Hampstead Heath near Kenwood House, where they used to take their dad in his wheelchair

The trauma was compounded by a police investigation, which saw five police cars show up at the family home. Anil and his sister’s phones and their father’s electronic devices were confiscated, and the siblings later had to give formal interviews. The investigation “hung over our heads for months”.

Afterwards Anil, who also went through the death of his mother Reena from cancer in 2008, began to campaign for changes to the law. “Bad deaths scar you for ever,” he says. “Whereas the law currently being proposed would lead to so many more good deaths, where people have the chance to come to terms with the reality of their death.”

‘I’m very happy with the life I’ve had’

-

Steve Gibson, photographed at Westway Coaches in south London, where he used to work

Steve Gibson, a 67-year-old former coach driver from south London, was diagnosed with motor neurone disease (MND) in January 2023. Timelines vary for the terminal illness, also known as ALS, but there is no cure or treatment. Gibson, who lives with his daughter Emma and two of his grandchildren, seems to be a slow progressor. But MND will take away his ability to walk, talk, eat and eventually breathe. He has noticed his already deep voice getting “croakier” due to increased difficulty clearing his throat. As a sociable person, losing the ability to communicate is especially scary; he recently started using a voice-banking app suggested by the NHS. “My big concern was: am I still going to sound like a south Londoner? And, secondly, can I swear? The answer to both was yes.”

Life-extending options for MND include a feeding tube and a tracheostomy to assist breathing. “Initially, I said, ‘Yeah, I want everything’, because you want to live for ever,” Gibson says. But he’s since changed his mind. After “a long discussion” with his neurologist, he signed a do not resuscitate order. He remembers taking care of his dad, who died from a different neurological disorder, in the last years of his life. “My mum couldn’t deal with it. Emotionally, it wrecks you. I don’t want to be like that.”

-

Gibson at Westway Coaches with Dave, his friend and former boss (top) and with his daughter Emma and granddaughter Nellie-Rose

Gibson wishes he could afford to go to Dignitas, and hopes changes to the law will happen soon enough for him to benefit. He wants to be able to decide when to call it quits. “I’m very happy with the life I’ve had. People ask if I’ve got any regrets. Well, yeah, maybe, but you can’t do anything about it. So we move forward as we are. That’s good enough for me.”

.png) 3 months ago

41

3 months ago

41