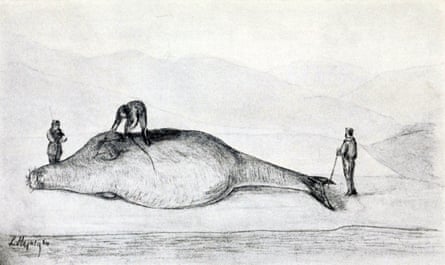

Iida Turpeinen is the author of Beasts of the Sea, a Finnish novel tracing the fate of a now-extinct species: the sea cow. Similar to dugongs and manatees, the sea cow was only discovered in 1741 by the shipwrecked German-born naturalist Georg Wilhelm Steller but by 1768 it had already become the first marine species to be eradicated by humans.

Translated into 28 languages and shortlisted for the country’s most prestigious literary award, the Finlandia Prize, Beasts of the Sea was described by the Helsinki Literacy Agency as the most internationally successful Finnish debut novel ever. Turpeinen, 38, a PhD student of comparative literature, is now a resident novelist at Finland’s Natural History Museum. Her book will be published in the UK on 23 October.

What inspired you to write the book?

I visited the Natural History Museum in Helsinki in 2016 and saw this very strange-looking skeleton of a big, bulky animal I didn’t recognise.

The placard said:“This is Steller’s sea cow, which went extinct 27 years after its discovery by science. There are only three to four skeletons that remain of this animal.”

And I was like: “OK, what happened here? There must be quite an interesting story behind these sentences.”

I discovered the sea cow was the first animal that brought up the scientific question: could humans have caused the extinction of this animal through hunting? At the time that the sea cow went extinct, in the 18th century, this question was laughed at.

People thought it was impossible – a ludicrous idea. Even a hundred years later, in the 1860s, the question was still controversial and fiercely debated. But of course, we now know that is what happened.

I had, for a long time, dreamed about writing a novel about the sixth mass extinction. And I realised this was the story I was looking for: this was the animal that would allow me to write about – and understand – why we are in the situation we are in today.

It was only recently – on the brink of the 20th century – that we gradually began to realise that we can be as much of a catastrophe to other species as a biblical flood, with all the responsibility this realisation brings about. For me, this explained a lot.

By writing the book, you’ve ignited a lot of interest in the sea cow. What do you think it is about the sea cow that captivates people’s imaginations, including your own?

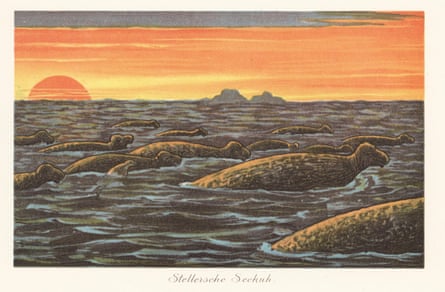

Imagine a huge manatee, the size of a whale, living in very cold waters among the remote islands of the Bering Sea. They had flippers with nails, like an elephant, and they moved about on the sea floor and grazed very close to the surface, in the kelp forest.

According to the few accounts we have, they loved to caress and touch each other, and hold their little ones. They were the perfect victim: big, gentle, lovable creatures that were very sociable and tactile. The dugong is a close relative.

I wanted this book to be an act of remembering and noticing extinction, and when I started writing it, I started dreaming about sea cows very often.

Now, I get a lot of feedback from readers saying they dream about sea cows as well.

There is something mysterious and yet relatable about this animal, something almost human-like, and I think it’s not a coincidence that the species has invited so many mythical interpretations. Wherever in the world there are manatees or sea cows, there have always been legends about mermaids.

Stories follow them – and I, too, felt that pull.

Why did sea cows become extinct?

Sea cows were mercilessly hunted after Steller wrote about his encounter with them, and when fur traders shot all the otters on islands nearby, the sea urchins multiplied and ate all the kelp. So while the sea cows were being hunted, they were also starving.

What touches me most is how peaceful and gentle they were. They could easily have capsized a boat, due to their size. Yet not once, to my knowledge, did a sea cow attack the people who were hunting it.

What impact did the book, which won the Helsingin Sanomat prize for best debut, have in Finland?

In researching the history of the sea cow, I never really encountered villains. More often, people acted in ways that proved harmful despite their good intentions.

Strangely enough, this dynamic became a side-effect of publishing the novel. After its release, people began flocking to the Natural History Museum in Helsinki to see the “main character” of the book for themselves.

Visitors were so eager to get close to the skeleton that some even touched it, despite its fragility.

Until then, the specimen had been on open display, but the museum eventually had to install glass walls around it to protect it from overly enthusiastic admirers.

I still don’t know whether it is tragic or comic that my book ended up endangering the remains of the sea cow.

What do you hope readers will learn from the story of the sea cow?

To question our way of thinking about our relationship with nature, to see where we have been and where we are, and to reflect on that.

It is very easy to judge historical characters and an historic event from today’s perspective, but when you look at what people like Steller knew, how they saw the world, it becomes very easy to understand their actions.

I think the act of remembering the sea cow is powerful. I hope that by inviting people to experience the loss of this fascinating animal, which deserves to be remembered, it will help us to gain perspective.

Beasts of the Sea by Iida Turpeinen, translated by David Hackston, will be published by MacLehose Press

.png) 11 hours ago

5

11 hours ago

5