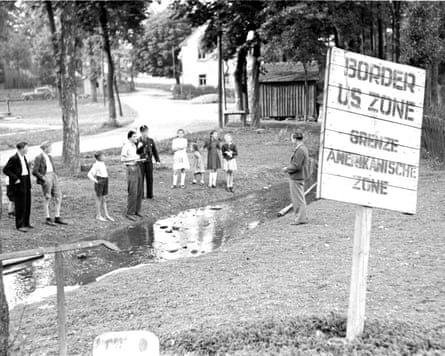

A creek so shallow you barely got your ankles wet divided a community for more than four decades. By an accident of topography, the 50 inhabitants of Mödlareuth, a hamlet surrounded by pine forests, meadows and spectacular vistas, found themselves at the heart of the cold war. They had the misfortune to straddle Bavaria, in West Germany, and Thuringia in the East, a border that was demarcated first by a fence and then by a wall. American soldiers called it Little Berlin.

Months after their own wall was breached, and even before their country had reunified in 1990, a group of local people set about memorialising their history. The work is about to come to fruition: on 9 November, the 36th anniversary of the fall of the (big) Berlin Wall, the German-German Museum Mödlareuth will open. It was officially inaugurated by the federal president, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, in early October, but the exhibition wasn’t quite ready. Addressing the villagers who lived through the old days, Steinmeier said: “You were witnesses of an inhuman division, which ripped families apart and turned neighbours into aliens.”

Even at its founding in 1810, the village cut across the Kingdom of Bavaria and the Principality of Reuss, a princely house best known for giving all its male members the name Heinrich and numbering them sequentially by birth. As Steinmeier told the audience, the quirk never stood in the way of the inhabitants drinking in the same pub, attending the same church and sending their children to the same school.

Then came the second world war. As soon as they arrived, the Russians erected wooden posts by the stream. For a year they took over the entire village, establishing their command in a house on the Bavarian side, adorning it with a picture of Stalin and a red star. The Americans convinced them to withdraw back over the brook. For a while, villagers could still hop over, though as restrictions tightened they were required to show ID, even though everyone knew who they were, and to return at night.

Then, in 1952, came barbed wire and the formal closing of the border. In 1966, as in Berlin five years earlier, a wall was built, with mines, tank traps and guard posts. The villagers could still see each other by climbing hills, but on the eastern side waving and shouting were prohibited. One woman was put on a Stasi watch list for responding “same to you” to a (Bavarian) villager who wished her “happy new year”.

I was told stories such as these by Robert Lebegern, the museum’s director, who has spent much of his working life creating it. Villagers were consulted early on about how much wall they wanted to preserve. They chose a stretch on the western fringe, close to where one of their own managed to escape in the dead of night with a ladder, after which the border was heavily reinforced.

Two watchtowers are preserved alongside a series of tableaux depicting the most dramatic dates in the village’s history. As we walk, Lebergen lists the regulations: nobody could come within 5km of the border. Farmers needed special permission to tend to their crops; the husband or wife could work the combine harvester but never both, in case they tried to make a run for it. Armed guards stood watch.

The border between West Germany and the GDR stretched 1,400km, from the Baltic Sea in the north to here in the south. Berlin is remembered and memorialised the most, but more than twice as many people (well over 300) died trying to cross it in rural areas than in the big city. Lebegern reminds me that 95% of escape attempts failed.

Most of Mödlareuth’s villagers were farmers or craftsmen, who adjusted to living in the grey zone between two ideological spheres by keeping their heads down and looking after their fields. They neither supported the communist regime nor resisted it, Lebegern explains.

For visitors, however, the hamlet became a kind of pilgrimage. About 15,000 came to visit every year, binoculars in hand, to gawp – and then quickly leave. In 1983, the US president, George Bush, was shown around by the German defence minister.

Twenty five years after reunification, Tannbach, a TV series about a fictional village resembling Mödlareuth, led to renewed interest.

The opening of the new museum – with a cafe, shop, cinema room and large car park – is likely to provide a further boost. Will it change the village? It is, in any case, changing all the time. Some of the original inhabitants on both sides have died; others have left. Newcomers have moved in, including a man from Leicestershire called Darren. His German wife, Kathrin, is a traffic cop for the Bavarian police. They live up a hill, past a chicken coop, on the Thuringia side.

The village is still divided, administratively at least, with different car number plates and postcodes. When Steinmeier visited, he was accompanied by the state premiers of both Bavaria and Thuringia. And when his foot crossed the brook, he was formally handed over by one police force to the other. History has moved on; the border has not.

.png) 8 hours ago

7

8 hours ago

7