Compared with the screaming scare campaigns of the 1990s, anti-drugs messaging is thin on the ground these days. So the casual observer may not realise that Britain has, quietly but surely, lost its “war on drugs”. Amid a steep rise in drug poisonings, a particularly striking statistic emerged last week. Between 2022 and 2023, cocaine-related deaths in England and Wales soared by 30%. The figure is now around 10 times higher than in 2011.

And that could be an underestimate. There’s often a time lag of two to three years between drug deaths and the coroner’s assessment on which these statistics are based, says Ian Hamilton, associate professor of addiction at the University of York: current rates are probably even higher. What’s more, not all deaths resulting from cocaine are included. The long-term damage that eventually ends in a stroke or a heart attack will not show up in these reports.

What is going on? One culprit is a precipitous rise in purity, which makes it easier to overdose by accident. Once cocaine was sold in a two-tier market: the cheap, heavily adulterated stuff, and the expensive, purer cocaine consumed by models, city traders and members of the Bullingdon Club. Now, according to the latest United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime report, cocaine in Europe has on average a purity of over 60%, compared with 35% in 2009. Today, even street cocaine rivals the top-end stuff of the 1980s.

This may in part be the unintended consequence of government crackdowns on cutting agents such as benzocaine, a dental anaesthetic. But the result is a drug that is often far stronger than users are expecting. This could be particularly true of generation X – now accumulating health issues – which came of age at a time of much milder cocaine: the highest rate of recent deaths in England and Wales is among men aged 40 to 49.

Another factor is price, which, despite inflation, has not budged for years. This is partly because supply is up in producer countries, partly because cocaine has a known street price: raise it, and customers go elsewhere; drop it, and they suspect something is wrong with the product. And if cocaine is better and cheaper, more people try it. A larger pool of users means more with undetected heart issues that a dose of cocaine might suddenly exacerbate.

It also means cocaine is more often mixed with other drugs, rather than consumed reverently, by itself, as a treat. This ramps up the danger. It is now so cheap and prevalent that drinkers use it to temper the effects of alcohol, in order to drink more. And to fill the gap left in the higher end of the market, there are complicated cocktails. Liam Payne, who died this month, had “pink cocaine” in his system: a drug that typically includes methamphetamine, ketamine, MDMA and crack cocaine. According to Harry Sumnall, a professor in substance use at Liverpool John Moores University, about 20% of the recently recorded cocaine deaths were in association with alcohol, and a third involved other drugs.

One important aspect of the death rate comes down not to the drug itself but to human psychology. Cocaine is increasingly normalised. It may be more dangerous than ever, but the more people take it, the more commonplace it seems, and the safer they assume it to be. In this way a vicious cycle is created: once there is a surge in cocaine use, it tends to be perpetuated.

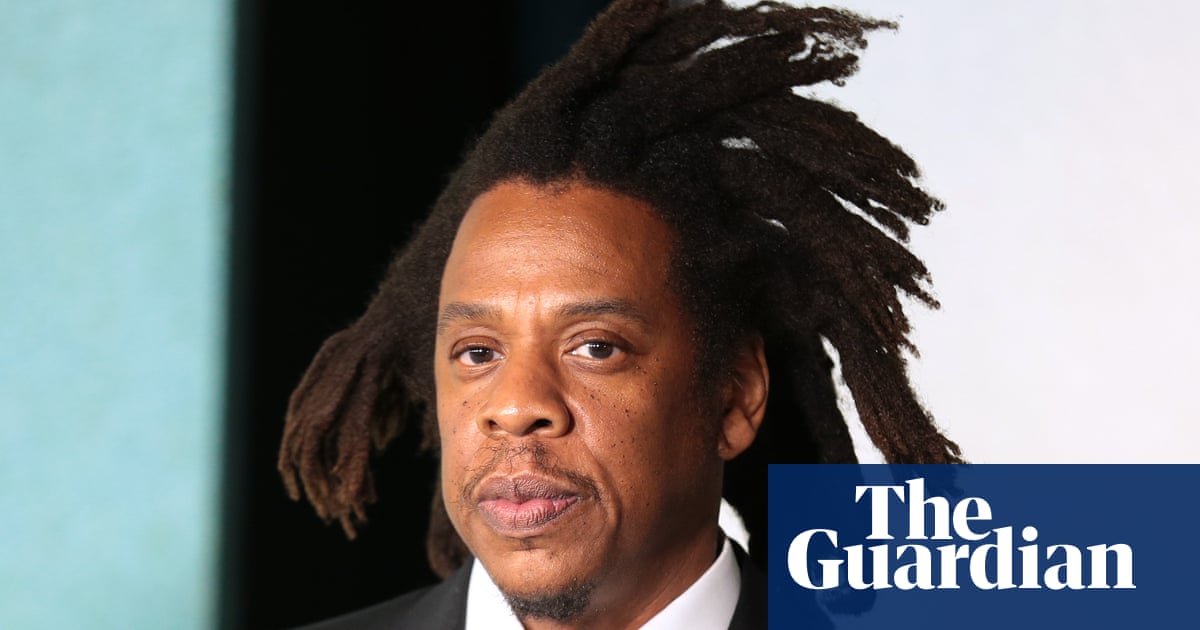

The drug has been normalised into different income brackets, too. It was once known as the yuppie drug, but has since gone through a radical rebrand: it is now found at all levels of society. It is so commonplace at football matches that it supersedes alcohol as a major safety issue on match days – helping to drive disorderly behaviour. A 2019 Home Office survey found that 35% of users were manual workers.

It has also become normal for older people to take cocaine. Traditionally, drug takers tend to give up the habit in their late twenties and early thirties, but a group within generation X is bucking the trend. The reasons are unclear, but it could be because there were more drug users in this generation to start with. “People who started taking drugs in the 1990s realised there weren’t enough police to go around and they were going to get away with it,” says Sumnall. “In the 70s and 80s young people were more scared of being caught.”

What can we do about this mounting death rate? The odd thing about drug problems is how helpless governments tend to be in the face of them – Britain can do very little about the purity and price of cocaine, mostly driven by international factors. Law enforcement only goes so far when people are consuming drugs en masse and mostly in private. And there is scant evidence that dramatic campaigns such as “Just Say No” did anything to deter people from drugs.

There are just two things that might work, says Hamilton. One is harm reduction: at present, treatment centres are mostly set up to help with opiates, and, unlike with heroin and methadone, there are no substitute drugs with which to treat cocaine addicts. There is some evidence, too, that data-driven education, rather than “scare” campaigns, might help break the cycle of normalisation. A recent study found that giving young adults information about how drugs affect the brain, backed up by reputable neuroscientific research, made them less likely to dabble.

after newsletter promotion

But another psychological block stands in the way of all this, which is that people tend to be reluctant to spend money to help drug users. In the 1980s, taxpayers were persuaded to fund harm-reduction programmes only because injecting heroin was associated with the wider spread of HIV. Then, under Tony Blair, spending on drug treatment was framed as a means to reduce crime. Can today’s voters be convinced that it is worth helping coke-addled 40-year-olds not to die?

We need to shift the mindset of cocaine users. But to do so we must shift our own. That may be harder than it seems.

Martha Gill is an Observer columnist

.png) 2 months ago

22

2 months ago

22