How can a democracy defend itself from an attacker who does not respect any democratic rules?

When your assailant uses corruption, blackmail, economic war, cyber attacks, covert campaigns and street violence – while all you have are inefficient courts and even slower international institutions. Can you lose your sovereignty by being too soft? If you respond with censorship or even cancelling elections, don’t you lose your values?

It’s a challenge for any country as the “international rules-based order”, for what it was ever worth, disintegrates. But it is perhaps sharpest in Moldova.

Nestled between Ukraine and Romania, the nation of 2.4 million is being targeted with relentless Russian malign influence operations – a small country made into a vast laboratory of subversion. As the president, Maia Sandu, put it when I met her earlier this month: “Our democratic processes were not designed for these kind of dangers to democracy.”

But Moldova can also be the place where democracies can learn to fight back against such attacks, while remaining true to themselves. As the US retreats from supporting a secure and democratic Europe, Vladimir Putin will become ever more emboldened. Britain and EU countries need to reinvent how we keep ourselves free.

And it’s desperately important to get this right in Moldova, a country that once formed part of the Soviet Union and is now an EU accession country. Moscow’s ultimate aim, Sandu argues, is to help bring its allies to power in Moldova, and then use Moldova to threaten Ukraine from the west and the EU from the east. In the short term, Moscow wants to show that it can use all measures short of outright invasion to keep nations it sees in its “zone of influence” chronically destabilised.

The more it can pull off such acts of malign influence, the more its status as a reborn superpower is enhanced, and the weaker the hopes for liberal democracies surviving in a dog-eat-dog world will seem.

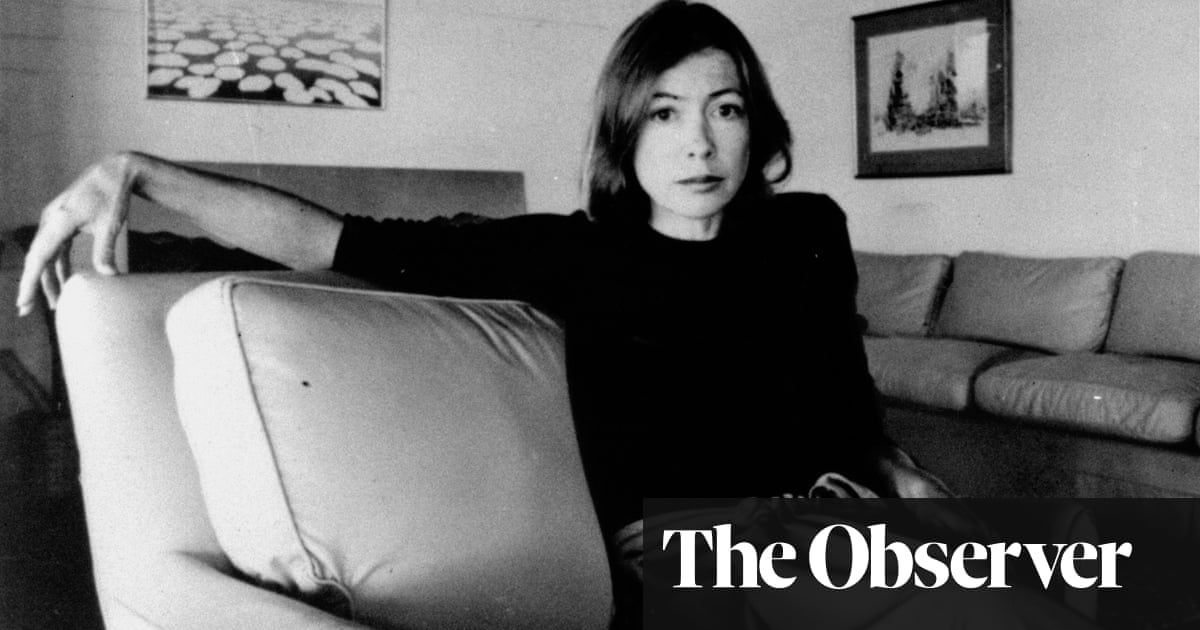

Sandu appears a personification of such hopes. A slight figure in the spare, high building of the presidential palace, she comes across as principled, neat, precise. She has won two presidential elections on a platform of EU integration, institutional reforms, rule of law, transparency and anti-corruption: the bouquet of concepts that were meant to denote membership of “developed” countries.

While so many of these terms have become hollowed out with hypocrisy, Sandu has a reputation for actually living them. Her father was a vet and the director of a cooperative farm in Soviet Moldova, where he was known for clamping down on workers stealing from the farm. Sandu studied management, attended Harvard, then spent two years as an adviser to the head of the World Bank. As minister for education she made her name introducing CCTV cameras in school exam rooms to stop bribes and cheating – it was unpopular at first, but worked.

In a country where people have often become politicians to either grow rich or protect their wealth, Sandu lives in a regular apartment. She’s unmarried, which has brought much misogyny from her rivals, who accuse her of not being “interested in what is happening in the country because she has no children here”; betraying “family values” and of being a “laughing stock, the sin and the national disgrace of Moldova”. She once tartly replied: “I never thought being a single woman is a shame. Maybe it is a sin even to be a woman?”

Sandu won re-election last year with 55%, but her referendum that committed Moldova to EU entry only squeaked through: 50% to 49%. As Sandu reels off the list of active measures taken by Moscow and its proxies over the election, worth an estimated $200m – 1% of the country’s GDP – the scale and scope is startling. Perhaps most audacious was a vote-buying scheme run by a fugitive oligarch, Ilan Shor, who has been indicted for stealing $1bn from Moldovan banks, and is now based in Moscow.

The scheme involved organising often poor, elderly people to register online accounts with a sanctioned Russian bank. They then downloaded a chatbot on the messaging app Telegram that told them how to vote, protest against Sandu or come to the pro-Russian party rallies. People would only get paid once they had completed all the tasks, and would often need to photograph themselves completing them.

Those involved could see the money hit their accounts – but they couldn’t take the funds from the sanctioned banks easily. So they were meant to put in more effort for the pro-Russian party to win and then remove the sanctions on the bank. “The motivation was very well structured,” admits Sandu.

The plot was foiled by the Moldovan police and undercover journalists at Ziarul de Gardă newspaper. A total of 138,000 bank accounts were identified – out of some 1.5 million voters. So about 10% of the electorate were paid to vote a certain way. But that could just be the tip of the vote-buying scheme: crypto payments and old-fashioned hard cash incentives were also used, with customs identifying a sudden wave of men travelling in from Moscow with hard cash totalling many millions in the run-up to the vote.

Shor boasted that he had many more people on his payroll.

And the question remains: what can be done in response? The courts, the Ziarul de Gardă editor Alina Radu explains to me, cannot deal with this amount of cases. So far a couple of thousand people are coming to trial. Going after the grannies who were paid to vote can look unseemly, but the higher-ups are well protected with lawyers. Police and reporters can play a cat-and-mouse game catching such operations, but the fact is they are worth the risk for the perpetrators.

“There are not many instruments that you have to protect yourself from these external influences,” admits Sandu. Such vote-buying operations have a particular impact in a small country, but they can be used in a targeted way in a larger country too – similar ones are already being reported in Bulgaria.

One possible response would be to just cancel elections – as Romania did in late 2024 when the authorities discovered a supposed Russian scheme to fund a pro-Moscow presidential candidate. But such radical steps make people deeply suspicious of democratic processes, and the cancellation of the Romanian vote was criticised by the new US government.

That’s the dilemma of facing such interference: ignore it at your peril, but if you react in a clunky way you only increase the division Russia wants to fuel.

Moldovan policymakers, for their part, decided to expose the operation publicly, hope the evidence would alert people to the danger and inspire them to vote and counterbalance the fraud. It just about worked. “When the society saw the danger, we had such a mobilisation that we managed to out-vote it,” explains Sandu.

The vote-buying scheme was just one example of the relentless subversion. Some operations play out in the military sphere. Moldova is home to the Transnistria region, a breakaway slice of the country that is de facto controlled by Moscow, which stations some 1,400 Russian troops there.

In the run-up to the election Russia organised exercises in the area, while its proxies pushed propaganda campaigns that Moldova would risk invasion if Sandu won. Moldova may be particularlyvulnerable to such intimidation, but it’s echoed in Kremlin policy across the Caucuses and central Europe.

Other operations are economic. Russia recently cut off gas supplies to Moldova and then blamed it on Sandu. Moscow has also been accused of cultivating priests who preach sermons denouncing the EU. Fake letters and posters that look as if they are from the EU or Moldovan authorities, but which discredit EU integration, have been distributed. One fake EU Commission letter claimed that all Moldovan officials who don’t speak English will be fired once the country has joined Brussels.

after newsletter promotion

Meanwhile, there have been many cyber attacks on official institutions. The police’s website was attacked 2,800 times in one night. The electoral commission was attacked in an attempt to cast doubt on the integrity of voting. Moldovan men were trained in Russia and the Balkans to preparefor street violence. ATMs have been disabled, followed by rumours that the banking system is collapsing.

And then there are the ever-increasing array of propaganda campaigns, on TV as well as online. In 2024 Shor used Facebook to run hundreds of ads that were viewed 155m times – in a country of 1 million Facebook users. Anonymous Telegram groups and other social media have pumped out lies and conspiracy theories: that the government helps the west steal Moldovan land, for example. Or that the EU will ban the words “father” and “mother” and replace with “parent number one” and “parent number two”.

To have a chance of meeting these challenges fully will need a level of coordination across sectors, countries and industries. To help mitigate the waves of online malign influence campaigns, for example, Moldova plans to work with the EU Digital Services Act (DSA) enforcement teams. The DSA is meant to ensure tech companies mitigate the “negative effects on civic discourse and electoral processes”. But it’s a new piece of legislation whose meaning is unclear, as is whether tech firms will comply.

In an ideal world the tech companies would set up war rooms to deal with the subversion, promptly and publicly show who is behind cover campaigns and give researchers access to data. The alternative is the chaos we see in Romania, where the lack of transparency from tech companies means no one can tell who exactly boosted the pro-Russian candidate’s campaign.

Moldova has another law on broadcast media to mitigate disinformation that can harm “national security”. It took a year to define this law with the Council of Europe so that it wouldn’t infringe on freedom of speech, and it still involves a slow process where TV channels are first warned, then fined for strategic, consistent campaigns. It might help to curb some long-term Russian efforts, but it’s no magic bullet.

But you can never regulate your way out of stopping subversive campaigns in a democracy – you need to learn how to engage audiences better too, argues Valeriu Paşa, the head of the WatchDog.MD thinktank. “We need to engage the audiences Russian propaganda reaches. They are often primarily Russian speakers, and there is little content for them from regular media.” Such audiences can have a romanticised view of life in “Great Russia”, and about the supposed injustices in what Russian propaganda calls “Gayeuropa”.

A new generation of communications strategies can compete. At the heart of the challenge is to engage the deeper emotional needs and fears that the Kremlin preys on. Simply debunking fibs about the EU won’t be enough, just “countering disinformation” misses the point. You need to engage the alienation and lack of community the Kremlin propaganda taps into so effectively. That means investing in non-news content too, from entertainment through to town halls.

But by the time you are pushing back against subversion, however, it is often too late. To pre-empt the types of vote-buying and disinformation operations Shor has become known for, one needs international investigations that disrupt the networks that support them. That means collaborating with security agencies across the continent on financial crime, and the growing use of crypto especially. Moldovan criminals and corrupt actors often operate from beyond the country, often in the EU and UK. Shor was based in Israel before Moscow.

Indeed countries who like to think of themselves as law abiding have been complicit over many years in sheltering the billions stolen from Moldovan banks by corrupt oligarchs. Sandu feels we can do more to stop them. “They continue to undermine our institutions here, trying to bribe judges and prosecutors in Moldova, finance illegal activities which undermine our democratic processes,” Sandu says.

And there are other steps Moldova’s partners need to take. Working together on cyber defences is a common priority – Russian hackers are hitting UK hospitals as well as Moldovan institutions. The domain server attacks on Moldova happen from inside the EU. Ensuring energy continues to flow is critical. Another is to undermine the Russian propaganda narrative that Moldova risks invasion if it dares disobey Moscow.

That can only really be achieved if the EU and Britain finally step up their defence capabilities – a need that is all the sharper with America’s clear signals it has minimal interest in standing up to Putin. Moldova is the perfect place to show we can.

The level of collective messaging to show political resolve, the amount of coordination between allies and support to democratic processes are not unfathomable. What it does take, however, is a new mindset. It means treating this challenge like the battle that it is. But the impact if we can prevail is high. By fending off Putin here, we make a clear statement that America leaving does not mean European security is lost.

Indeed as the US pivots to Moscow, Moldova’s vulnerability seems less atypical but rather the norm for a Europe and Britain that will be left increasingly to fend for itself. And in that sense Moldova is well ahead of working through the fraught challenge of finding a democratic way to defend from undemocratic enemies.

Despite relentless pressure from the Kremlin, Moldova has, Sandu says, managed to “take down a corrupt government; hold free elections and a peaceful transitions of power”.

Sandu might belong to the generation of politicians who were committed to an idea of progress where countries try to learn from and become more like “the west”. But now it’s we who need to learn from her. We are all more Moldovan now.

.png) 6 hours ago

2

6 hours ago

2