For a religious leader, the allegations were scandalous. Mistresses, illegitimate children, embezzlement. But in 2015, the head abbott of Shaolin monastery, the cradle of Zen Buddhism and kung-fu in China, was untouchable. Shi Yongxin, the so-called “CEO monk” who turned the 1,500-year-old monastery into a commercial empire worth hundreds of millions of yuan, held firm. Soon he was cleared of all charges.

But 10 years later, the 60-year-old monk was not so lucky. In July, not long after Shi returned from a trip to the Vatican to meet the late Pope Francis, the Shaolin Temple released a statement saying that he was being investigated for allegedly misappropriating funds and for fathering illegitimate children with multiple mistresses. Less than a fortnight later he was dismissed and stripped of his monkhood. He has not been heard from since.

Shi’s downfall, for accusations similar to those made – and survived – in 2015, was the most high profile in a series of scandals that have rocked China’s Buddhist temples in recent months.

The controversies reveal the increasingly precarious position of influential religious leaders in China, as the official support for the commercialisation of religious sites gives way to an emphasis on frugality and political obedience.

In July, a well-known monk called Daolu – real name Wu Bing – was stripped of his title by the Buddhist Association of China after police in Zhejiang province said that he was being investigated for alleged fraud. Wu is accused of soliciting public donations under the guise of collecting money for unmarried pregnant women and needy children, which was actually spent on personal extravagances. It is not clear if Wu, who has not been heard from since the news broke, disputes the claim. The Guardian was unable to reach him for comment.

In August, a video of monks from Hangzhou’s Lingyin Temple sitting around a table counting wads of cash went viral, catapulting the 4th century hall of worship into a social media storm.

“Those who worship Buddha become poor, and monks become rich,” wrote one social media user.

There is nothing inherent in Chinese Buddhism that forbids the accumulation of wealth, says Kin Cheung, an associate professor of East and South Asian religions at Moravian University. In medieval times, monasteries stood in for banks, loaning cash to merchants while charging high interest rates.

But while raising money for religious purposes is seen as acceptable, growing personally rich can put a mark on one’s back.

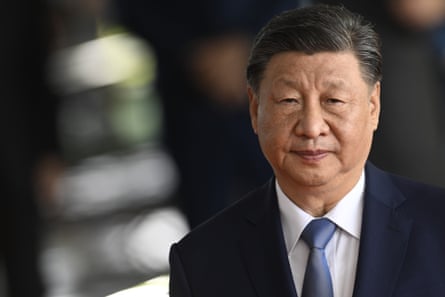

The opprobrium comes from ordinary people who see riches as being spiritually corrosive, and, increasingly, from the government, which under the leadership of Xi Jinping has cracked down on excess wealth and corruption.

Overhauling Shaolin Inc

China’s temples have swung in and out of political favour in modern Chinese history. During the Chinese Communist party’s (CCP) land reform campaign in the 1950s, monasteries were stripped of their assets. Countless religious sites were destroyed or damaged in the cultural revolution in the 1960s and 1970s. But as China entered a period of economic reform and opening up in the 1980s, temples were back in vogue, with many turning to tourism to support themselves, often with explicit government support.

Of the prominent abbots who appeared to benefit personally in this period, Shi was the biggest. Born Liu Yingcheng, Shi joined the Shaolin temple in Henan province as a 16-year-old in 1981. Back then, the temple was in ruins. But as Shi rose the ranks to head abbot, he negotiated with the local officials to re-open prayer halls and sell tickets to tourists. Soon, millions were flocking in, with the local government taking a 70% cut. Gift shops selling Shaolin-branded merchandise also opened, and Shaolin Inc was born.

Shi’s star rose in the process. In 2006, the Dengfeng city government gave him a luxury sports car worth 1m yuan (£103,257) to honour his contributions to local tourism. He shrugged off criticism, saying “Monks also need to eat.”

With money came political power. Between 1998 and 2018 he served as a delegate to China’s National People’s Congress. Over the years he met Nelson Mandela, Henry Kissinger and Queen Elizabeth II, and took a troupe of martial arts monks to Moscow for a special performance at the invitation of Vladimir Putin. It led one worker near the Shaolin monastery to remark that the political heft of local CCP officials seemed paltry in comparison with Shi.

The Shaolin temple’s popularity rose as the so-called “temple economy” in China boomed – its market size is predicted to reach 100bn yuan by the end of this year.

As China suffers with stubbornly sluggish economic growth, temples in theory are a gift to both local governments and ordinary people. The authorities benefit from increased domestic spending as people flock to temple-cum-tourist attractions, while people struggling to find work or fulfilment in Chinese society are increasingly turning to religion for spiritual guidance.

But temples also must tread an increasingly narrow line between popularity and political obedience. “The Chinese government is very attentive to how much power is being amassed by religion,” Cheung says.

Experts think that Shi’s downfall could have been due to a loss of political support rather than any specific wrongdoing.

“It’s almost always that there is something else [going on] that has to do with patronage,” says Ian Johnson, the author of The Souls of China, a book about religion in China.

Xi has shown a particular interest in traditional Chinese religions. Early in his career he helped to re-open important Buddhist temples and turn them into tourist attractions, a blueprint for how the officially atheist Party could work with religion.

But in more recent years, Xi has tried to dial back the excesses of religious commercialisation. In 2017, Beijing revised its regulations on religious affairs, noting that Buddhist and Taoist sites risked damaging the “pure and solemn image” of China’s ancient religions. The new regulations stipulated that Buddhist and Taoist sites must be non-profit operations and banned the excessive promotion of paid-for religious practices such as burning incense and drawing lots for fortune-telling.

Now it seems that the Shaolin monastery, set in the jagged Song mountain range, is being brought to heel. Upon being installed in August, Shi Yongxin’s replacement, an abbot called Shi Yinle with a reputation for frugality, announced an overhaul of Shaolin Inc. He halted commercial performances, banned expensive consecration rituals, said he would remove temple shops and said that he would eliminate other unpopular fees.

“Shaolin should return to its true essence,” said Xie Chuanggao, a 57-year-old retired civil servant who visited the temple in August.

But so far, the anti-commercialisation drive is patchy at best. Yellow-robed monks stage daily, spellbinding martial arts that are free – for anyone who has bought an 80 yuan ticket to the temple complex. The site is still packed full of shops, which on a warm summer’s day are themselves packed full of tourists who have arrived by the busload to spend their yuan on kung-fu pandas and Lafufus.

And not everyone takes such a harsh view on Shi.

Tom Li, a 21-year-old medical student at Henan University, visited Shaolin on his summer break. “Without [Shi], the Shaolin temple would not have achieved so much. It would not have been known internationally … there are pros and cons, but you can’t deny his contribution”.

Li said that he wasn’t put off by the sight of monks enjoying luxury goods. “After all, I’d also want to drive a range rover”.

The Shaolin temple declined an interview request.

Additional research by Lillian Yang and Jason Tzu Kuan Lu

.png) 1 month ago

40

1 month ago

40