In 1986 the psychiatrist Dr Aggrey Burke, along with his colleague Joe Collier, had gathered evidence that their employer, St George’s hospital, and other London medical schools, were discriminating against women and people with “foreign sounding names” in their admission processes. Burke and Collier, both then senior lecturers at St George’s, decided to blow the whistle. They published a paper that led to a Commission for Racial Equality inquiry, and wholesale changes to the admission policies at medical schools across the capital. Burke knew the risk the pair were taking, saying it was “as though one had offended against the whole system; we were blamed, unfairly treated and made to feel that we were outcasts”.

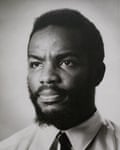

As the first Black consultant psychiatrist in the UK, Burke, who has died aged 82 of prostate cancer, was at the forefront of challenging mental health systems to treat Black people with fairness, and of supporting those caught up in the criminal justice system. The most notable case he worked on was that of the Rastafarian Stephen Thompson who, in 1980, was sectioned in Rampton secure hospital in Nottinghamshire because he violently resisted prison officers cutting off his locks, ignoring the religious significance of his hair. Burke was one of the independent psychiatrists who intervened, and he managed to have Thompson released after what he humbly called a process of “negotiation”.

Already engaged in community activism, Burke was on the ground in the aftermath of the New Cross house fire in January 1981 that claimed the lives of 14 Black teenagers (13 on the night, and a survivor who later took his own life). Dubbed by many as the New Cross massacre, it was one of the pivotal events in Black British history. The silence of politicians and the press in response to the tragedy sparked a mass protest movement including a Black People’s Day of Action that saw about 20,000 people marching through London and the slogan “thirteen dead, nothing said”. Burke helped to set up a group for survivors and the community to process the pain and grief. He supported the survivors through both of the inquests (1981 and 2004), and as late as 2022 was still working with young people in the area.

Born in St Elizabeth parish, Jamaica, Aggrey was the son of Edmund Burke, a senior civil servant who was sent to Britain in 1958 to ease tensions in the aftermath of the Notting Hill race riots, and Pansy (nee Balfour), a teacher. Along with Pansy and three of his five siblings, Aggrey, then aged 16, joined his father the following year, and they lived as one of the few Black families in Kew, west London. In Jamaica he had attended a number of government-run schools before winning a scholarship to the prestigious boys’ boarding school Jamaica College. His sister Marilia said that Burke “became aware of another world” at the school, which aimed to develop future leaders. This was in stark contrast to his schooling in the UK, at Shene grammar, where he felt that he was always on the outside and “could never feel part of the thing”.

In 1962, Burke enrolled at the University of Birmingham medical school. He found respite from the predominantly white university campus by volunteering for the Harambee Organisation in the Handsworth area of the city, which then had one of the largest Jamaican populations in the country. Burke helped at the organisation’s “supplementary school” that aimed to give Black children the education that mainstream schools were failing to provide.

During his studies Burke visited his parents in Ethiopia, who had moved there while his father was working for the UN, and visited Shashamane, the village set up for Rastafarians by Emperor Haile Selassie. After graduating from Birmingham in 1968, Burke completed his psychiatric training at the University of the West Indies in both Jamaica and Trinidad. By 1971 he was a registrar at the university hospital in Mona, Kingston, as well as teaching at the university. He returned to Birmingham University in 1972 for a research fellowship, before being appointed senior lecturer in psychiatry at St George’s hospital in 1976, progressing to consultant psychiatrist. No further promotion came before his retirement there, a fact that Burke felt was linked to his whistleblowing activities. Nevertheless, despite not receiving the formal title, he was affectionately referred to by many as the “people’s professor”. In 2024, Birmingham awarded him an honorary doctorate.

His commitment to the Black community continued throughout his life. In 1991 he was a co-founder and vice-chair of the George Padmore Institute, an archive above Britain’s oldest Black bookshop, New Beacon Books, in Finsbury Park, north London, and remained an active trustee until his death.

He published countless articles on Black mental health and was a source of support and inspiration for those trying to break into and survive in the field. In 2019 Burke was honoured as one of the 100 Great Black Britons, a list created to celebrate high-achieving Black individuals over the past 400 years. The following year the Royal College of Psychiatrists presented Burke with its President’s medal, and in 2023 created the Aggrey Burke fellowship for Black medical students.

Marilia survives him, as do three nephews and two nieces.

.png) 1 month ago

42

1 month ago

42