Donald Trump was an angry man. “It’s a cheap, defamatory, and politically disgusting hatchet job, put out right before the 2024 Presidential Election, to try and hurt the Greatest Political Movement in the History of our Country,” the Republican nominee wrote in an early morning post on his Truth Social platform.

Trump was referring to The Apprentice, a film that chronicles his early rise. “So sad that HUMAN SCUM, like the people involved in this hopefully unsuccessful enterprise, are allowed to say and do whatever they want,” he added, triggering all sorts of freedom of speech alarms.

But could the former president be right? Is The Apprentice designed to change the course of next month’s election – and might it succeed? Disappointing box office returns so far suggest this is unlikely. History is also a guide.

Since President Woodrow Wilson screened The Birth of a Nation, a film celebrating the Ku Klux Klan, in the East Room of the White House in 1915, politics and popular culture have had a push-and-pull relationship. Last month the fictional president Martin Sheen and other cast members visited Joe Biden’s White House to celebrate the 25th anniversary of The West Wing.

Some film-makers are explicit in their intention to affect election outcomes, releasing their work just a week or two before polling day. Others come from the opposite direction, reckoning that an election year is the perfect time to draw attention to a political movie.

The Guardian chose films from each election year of the 21st century and interviewed the people who made them.

2000: The Contender

A political thriller starring Joan Allen, Gary Oldman and Jeff Bridges tells the story of a female senator, Laine Hanson, who is in line for the vice-presidency only for disinformation about her past to threaten her confirmation.

Rod Lurie, its writer and director, says over Zoom from a film shoot in Bulgaria: “George W Bush had just announced that he was going to run. My daughter was about seven years old and she asked me, Daddy, why are there no women presidents? I said, well, I promise you the time is coming.

“I realised I wanted to make a movie in this arena and discuss what would be the unique difficulties of a woman running for the presidency or running to have some sort of power, in this case being selected vice-president.”

Lurie, who received an assist in the editing room from Steven Spielberg, adds: “We did a lot of research and went to Washington DC and met with several leaders and female leaders – or tried to – and learned quite a bit about the process. What I figured was that the sexism was – and still is – such an enormous part of not just Washington DC but also of much of the American electorate.”

Many observers thought the The Contender was inspired by the scandal of Bill Clinton’s affair with Monica Lewinsky, a 22-year-old intern, which led to his impeachment. But Lurie insists that the true impetus came from the confirmation hearing for the supreme court justice Clarence Thomas, in which the law professor Anita Hill made allegations of sexual harassment but found herself under interrogation by male senators.

“How easy it is to rip apart a woman sexually – much easier than it is a man – and we’re seeing that today, of course. There is simply no escape for a woman who is slut-shamed back then or even right now. The men can be complete dandies, can have had multiple affairs, and at this point nobody touches it.

“The insinuations that they put Kamala Harris through are to me baseless but also ironic and very upsetting. More than one person has brought up the connection between what’s happening now and what happened to the character in The Contender.”

But Lurie was not trying to influence the 2000 election, eventually won by Bush, a Republican. “There was nothing in that movie that would be anti-Bush at all. We didn’t attack Republicans as Republicans so no, that was not on my mind.”

But when Lurie went on to make the TV series Commander in Chief, in which Geena Davis played a female president, his political motivations came under scrutiny. “We were doing a press conference and they did a clip from the show, the entire cast and I were on stage and as the lights are coming up, I hear the first question from some reporter in Dallas saying, ‘Is this a complete shill for Hillary Clinton?’

“That’s the first thing that people thought and the truth is that, no, I wasn’t being a shill for Hillary Clinton but I was being a shill for a woman president.”

2004: Fahrenheit 9/11

“On its surface it seems like movies that deal with politics, especially during an election year, have absolutely no impact,” the documentary maker Michael Moore says by phone from New York. He would beg to differ.

Moore won an Oscar for his documentary Bowling for Columbine on what was the fifth night of the war in Iraq. Accepting the award, he delivered an impassioned anti-war speech that described George W Bush as a president who “sends us into a fictitious war for fictitious reasons”. He was booed off stage at a time when the majority of Americans supported Bush’s decision to invade.

But Moore was determined that this historic foreign policy blunder would be his next documentary subject. “It was like, we just have to do this,” he recalls. “Everybody told me not to do it.”

The movie was Fahrenheit 9/11, a devastating critique of Bush and Tony Blair’s deadly folly in Iraq. It received a 20-minute standing ovation at the Cannes film festival. Moore later learned that the White House became alarmed and commissioned focus groups to examine its potential impact on Republican voters.

After a rigmarole over funding, the film gained a national release in June. On its opening weekend it generated domestic box office revenue of $23.9m and went on to make $119m and a similar amount worldwide.

This was an election year and Moore wanted Bush to lose to the Democratic challenger, John Kerry. “The story has been since then that the movie had no impact, Bush won, end of story. But Bush won by one state, Ohio, and by 118,000 votes. It was the smallest victory a wartime president in the history of the United States ever had. We were never going to get rid of Bush in that year because Americans are too nervous about throwing out a president during wartime.”

But after being released on home video and shown on cable television, Moore contends, Fahrenheit 9/11 did percolate into the consciousness of the electorate with far-reaching consequences for national politics.

“Between the end of 2004, when the election was, all the way through 2005 and then in 2006, we had so many millions of Americans see the film and the truth about how we got into it, what it did to people. What happened in 2006? The Republicans are thrown out. Bush has got the war going on and now he doesn’t have the House or Senate.”

For Moore, the lesson was that the American people will come around and do the right thing. “You’re not going to put a movie out in June and expect to change the electorate by November. But two years later people could see what a miserable thing the war was – ‘Mission accomplished’, all the bullshit and dead American boys coming back every week – and so there was this massive shift from I was a pariah, I was anti-American, etc to wow, he stood on the stage and told us the truth and we booed him. The rest of the next five years were people, especially in Hollywood, apologising to me for having been there, having booed me.”

Twenty years have now passed. US forces withdrew from Afghanistan and Iraq. Moore made Fahrenheit 11/9, a documentary about how the US ended up with Donald Trump in the White House. Bush’s vice-president, Dick Cheney, has endorsed the Democrat Kamala Harris for president.

Moore reflects: “The whole Iraq and Afghanistan era was very sad for us. But the best letters I got were from the vets, the people that were there in Iraq and Afghanistan. The last people that you would think would be writing to me were writing me because they’d seen Fahrenheit, they were there in Iraq and they were grateful that somebody was willing to stand up and tell the truth.”

2008: W

The next Bush blockbuster was Oliver Stone’s biopic W, which portrayed the president (Josh Brolin) struggling to escape the shadow of his father, President George HW Bush (James Cromwell). Stone said: “I want a fair, true portrait of the man. How did Bush go from an alcoholic bum to the most powerful figure in the world?”

Stanley Weiser, who wrote the screenplay, says by phone from Santa Monica, California: “I felt that there were two dynamics. One was the father-son relationship and the wayward son basically was unfavourably compared to his brother and was considered profligate and going nowhere and having to prove himself. The other was the path to a new war in Iraq and how Bush was hornswoggled by [Donald] Rumsfeld, [Dick] Cheney and [Paul] Wolfowitz into believing that there were weapons of mass destruction. And Bush being so impressionable.”

Although Stone is known for his strident political views, Weiser focused on art rather than activism. “I tried to separate myself from the man and write about him both from his point of view and also in an objective political arena. I tried to separate myself pretty much from my own political feelings as I was writing it and trying to get into his head.

“I knew there would be people who felt that I was going too easy on him and those who felt that I was too critical. I knew going in what that reaction would be but I tried as best I could to be as accurate as I could, according to all the research I had done.”

W was released in mid-October 2008, just before the presidential election between the Republican John McCain and the Democrat Barack Obama. But Weiser was not thinking about its political consequences. “I had tunnel vision about what I was writing so I wasn’t thinking about that. The task at hand was quite hard and so I filtered that out.”

Bush’s approval rating was low when he left office but his reputation has grown in recent years, partly because many regard him as a moderate figure compared with the extremism of Trump. Weiser adds: “There’s this whole revisionist take on Bush and it’s quite extraordinary because you think of the number of thousands of people who were killed in the Iraq war. Trump, as horrendous as he is, did not have a major war.”

Weiser is glad that W stands as a warts-and-all chronicle of Bush’s presidency. Does he believe that movies can sway elections? “I do, but not significantly because the vast majority of voters don’t bother to go to the movies. Their minds are made up. They feel what they’re seeing must be a mischaracterisation or partisan politics. Younger people can be swayed so movies can make a difference but just not that considerable.”

2008: Recount

Recount turned dimpled chads and other shenanigans in Florida during the 2000 presidential election into an edge-of-the-seat thriller starring Kevin Spacey and Tom Wilkinson. Danny Strong wrote the screenplay.

He says from Los Angeles that Recount was inspired by the British playwright David Hare’s play Stuff Happens, written in response to the Iraq war. “I walked out of the theatre just so inspired by the play, thinking I want to write something like that. I want to write a true story, inside accounts of a major political event and then the idea of the Florida recount popped into my head.

“This was 2005 so it was several years after the recount had happened. There was nothing about it in concept where I was thinking, I’m going to write this to affect the election. It was literally just an idea for a movie I came up with that I thought could be an exciting film. Then when I started researching the actual Florida recount, I just thought, this is an incredible story.”

Strong continues: “The circumstances were unbelievable and then the way in which the two sides fought the fight was completely fascinating. There’s a line in it where James Baker says, ‘we’re the middle of a street fight for the presidency of the United States,’ and that’s what was happening. It was literally a street fight for the presidency. I thought the story was a timeless story, a story for the ages. It deserved to be codified as a film.”

But for Strong, the notion that such a film would sway an election is like looking through the wrong end a telescope. “I don’t know if people believe it’s going to impact voting. The sense is that it will have much more impact, media attention, buzz, interest in an election year.

“It motivates people to get the film made. It’s hard to get any movie made. Thinking like, ‘oh, if we could get this out for the election in the election year, it can really pop and have some buzz’ is certainly a motivating factor.

“I know with both Recount and Game Change we wanted the films to come out in the spring, not in the fall, to have a little bit of shield from criticism that we were trying to affect the election. There was a sense of we were trying to avoid that exact criticism so we were pushing for earlier in the year than later in the year.”

2012: Game Change

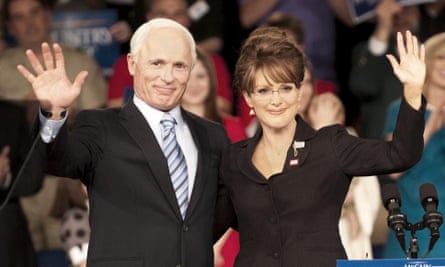

Game Change told how Sarah Palin, the governor of Alaska, was plucked from relative obscurity to become Senator John McCain’s running mate in the 2008 election – foreshadowing an era of rightwing populism.

Recount’s director, Jay Roach, had approached Strong to make a film about Palin. He was reluctant at first but then he read the book Game Change by John Heilemann and Mark Halperin and immediately spotted its cinematic potential. The film starred Julianne Moore as Palin and Woody Harrelson as the political operative Steve Schmidt, who first floated the idea of her becoming the vice-presidential nominee.

“This is another one of those one for the ages stories of someone who’s thrust in this position and seems to be way in over her head,” Strong says. “There seemed like a lot of drama there. You had Steve Schmidt and the powerful arc of this guilt he had about promoting her to that position, a sort of warped Pygmalion story. It seemed like a rich tale.

“We felt like we were telling a story that was showing the creation of the Tea Party [a conservative revolt fuelled by rage against elites, distrust in government and racial hostility to Barack Obama]. That was definitely part of it but I don’t think we realised how in many ways she was the first sign of how powerful populist messaging could be in the Republican party. That’s why Game Change still gets talked about.”

But again Strong was not aiming to tilt the 2012 election between Obama and the Republican Mitt Romney. “I don’t come out writing these movies and making these movies thinking this is going to affect the election. It’s more of, I think the story’s amazing and fascinating and I want to tell the story, so how best can this story succeed? Well, in an election year there’s going to be more interest in it than not.

“But in both Recount and Game Change it was a goal of ours to not come out too close to the election because we didn’t want this perception of it to be soured in that way. We still wanted it to live on as a piece of art that’s saying something as opposed to a piece of propaganda.”

2016: All the Way

The playwright Robert Schenkkan drew on oral transcripts, film footage, newspaper reports, White House phone calls, speeches and FBI files to portray the first year of Lyndon B Johnson’s presidency following the assassination of John F Kennedy. All the Way was a hit play on Broadway, winning a Tony award, and adapted for an HBO film starring Bryan Cranston.

Schenkkan had worked on the play for several years before the 2016 election, in which Donald Trump defeated Hillary Clinton. “But the issues at the heart of it – the struggle about power and morality and the kinds of choices one is forced to in a constitutional representative democracy like America – were incredibly relevant,” he recalls.

“I know for a fact that [the Democratic leader] Nancy Pelosi, who came to the opening and saw it, then returned a second time with members of the Democratic caucus because she wanted them to see what is possible if you embrace your power. I’m very pleased she felt that way about it but I can’t say that there’s a long list of legislation that resulted from it.”

All the Way features Martin Luther King and the struggle for the Civil Rights Act, which Johnson signed in 1964. Schenkkan continues: “The racial politics, which are very much at the heart of it, has never abated. If anything, it’s gotten extraordinarily worse. We’ve taken a step back.

“Trump has legitimised the coarsest expression of the racial animus that has been at the heart of American politics since before the civil war. I was very much aware of that and very much trying to help an American audience appreciate this movement and how potent and powerful it’s been and how it has shaped American politics for such a long time.”

Schenkkan has also written hot-off-the-press political works such as Building the Wall, a response to Trump’s anti-immigration rhetoric and policies, and The Investigation, which adapted the report by the special counsel Robert Mueller on contacts between the Trump campaign and Russia. “You do what you can and hope it makes a difference,” he says.

Although he remains sceptical of the idea that a single movie could alter the race for the White House, Schenkkan does recognise the power of art to have a broader and deeper influence. “Film has sometimes had a potent effect not so much on specific elections but certainly on political movements.

“The Birth of a Nation absolutely affected and continues to affect American politics in the most terrible way; similarly [the 1935 German Nazi propaganda film] Triumph of the Will. But neither of these changed an election. Politics can make for important movies but I don’t think movies make significant politics.”

2020: Borat Subsequent Moviefilm

The sequel to Borat was released just before the 2020 poll with the overt aim of embarrassing Trump, who was seeking re-election, and his acolytes. The film’s star, Sacha Baron Cohen, told the New York Times that he wanted to release the film before the election as “a reminder to women of who they’re voting for – or who they’re not voting for”.

Borat Subsequent Moviefilm was shot in secret and not announced until shortly before it came out. Its director, Jason Woliner, says by phone from California: “Sacha was inspired to bring the character back and to do the film because of Trump and what Trumpism and everything had done to America and definitely made the movie with the intention of motivating Americans to vote him out back in 2020. It was released the weekend before the election and it did make something of a splash.”

Most memorably, Trump’s personal lawyer Rudy Giuliani is seen reaching into his trousers and apparently touching his genitals while reclining on a bed in the presence of the actor playing Borat’s daughter, Maria Bakalova, posing as a TV journalist (Bakalova also appears in The Apprentice, playing Trump’s wife Ivana). Woliner had no idea that the audacious sting would work as well as it did.

“From the inception the movie was about Borat being given the task of delivering his daughter to a prominent man in the Trump universe and Rudy was there from day one,” he recalls. “We’d actually booked Mike Lindell, the MyPillow guy, as a back-up for the day after but Rudy worked and we fled.

“It was pretty wild: minutes after it blew up, we all escaped that hotel and within minutes there were, I think, seven police cars outside and we got word that every cop in New York was looking for our crew. We had to get our whole crew out of the state that night. It was very exciting.”

As the embarrassing clip generated a media firestorm, Giuliani was forced into a series of defensive media interviews. The former New York mayor tweeted: “The Borat video is a complete fabrication.”

Woliner says: “Who knows what impact it had but certainly at the time Rudy was not how we think of him right now. He was actually pretty close to Trump and was a pretty prominent surrogate, basically, and was pushing that whole Hunter Biden laptop story. If anything, the way Rudy came off in the movie probably discredited him and maybe shut that story down a bit, but who knows? Maybe it had a small impact.”

But his reputation was in freefall. Four days after the election, which Trump lost, Giuliani held a farcical press conference at Four Seasons Total Landscaping, a small business in north-east Philadelphia, near a sex shop and a crematorium. Presumably the Trump campaign had intended to book the upscale Four Seasons hotel but got confused. Later that month Giuliani gave a press conference with what appeared to be dark hair dye streaking down his sweaty face.

Woliner observes: “Everything he did in real life in the month following was absolutely funnier than anything that we may have done.” Giuliani has lost his law licence in New York state over his actions to spread lies about voter fraud in the 2020 election and become a figure of ridicule.

Giuliani was not Borat’s only target. During the edit, Woliner rewatched Mike Pence giving a speech to a conservative conference earlier in the year in which the vice-president – who was interrupted by Borat in a Trump costume – boasted that there were few Covid-19 cases in the US and the threat was contained.

“Just seeing that in context when the whole world is shut down and the administration has failed so much on Covid, we felt these were powerful moments to include. Again, I have no idea what impact it actually had but it’s rare that a movie can be released at a moment so relevant to it content. You don’t get to see it too often, especially because studios are often in the business of attempting to look non-partisan. We were very fortunate that Amazon put it out in the way it did.”

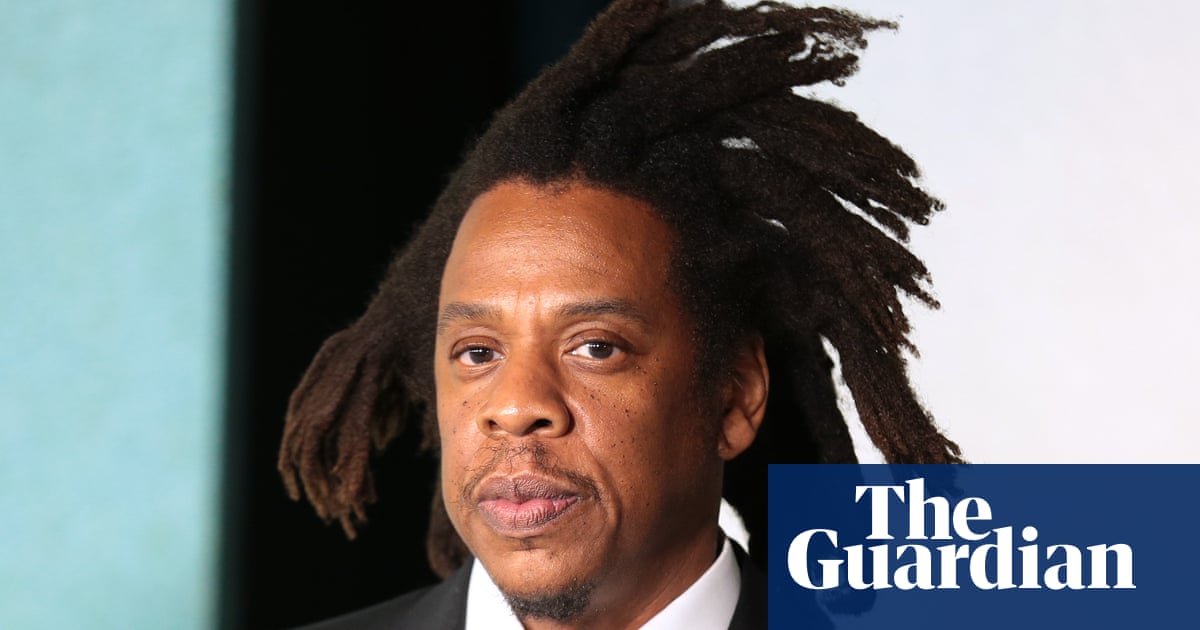

2024: The Apprentice

The new drama stars Sebastian Stan as Donald Trump in his years on the make in the 1970s as a New York property developer and his mentor-protege relationship with the lawyer-political fixer Roy Cohn, played by Succession’s Jeremy Strong. Ali Abbasi, the film’s director, plays down its potential impact on next month’s election between Trump and Kamala Harris.

He says: “The idea that we, with an independent movie that had a difficult time getting distribution, could affect the US election, which is the most gigantic, money-sucking endeavor of politics in human history … I wish I had those powers, honestly. That would be great.”

Abbasi adds: “I don’t think movies change elections, generally speaking – not in India, not in Iran, not in the US, because people have bigger, other very concrete worries, like things that affect their everyday life.

“What I want to achieve is not changing the election. I want to achieve the change of mindset, if I can, with people, because, look, as dangerous as is the rhetoric of alienating people by saying they’re eating cats and dogs and they’re rapists and whatnot, as dangerous is alienating the other side, so much that people feel it’s legitimate to shoot them, you know?”

Some observers have suggested that the film might in fact elicit sympathy for Trump by turning him into a three-dimensional character rather than a cartoon villain. “People keep saying, oh, you guys are humanising too much,” Abbasi says. “I’m like, there is no such thing as humanising too much.

“If I can somehow get the American people to realise that it’s not about Democrats, it’s not about Republicans, it’s not about the political system, it’s about the whole justice system, the whole way you keep and manipulate power in this country, and then there’s the story of this guy – Roy Cohn is a complicated guy – flawed people, but still people. If I can get people to experience that, then whoever they want to vote for, that’s their business.”

.png) 2 months ago

14

2 months ago

14