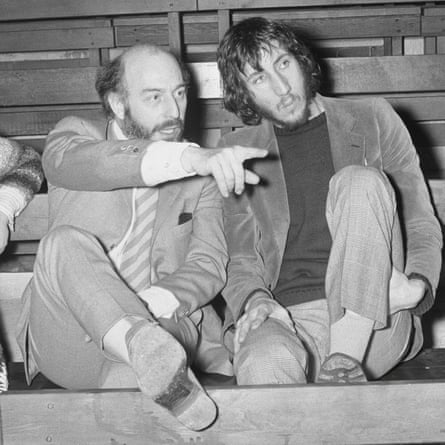

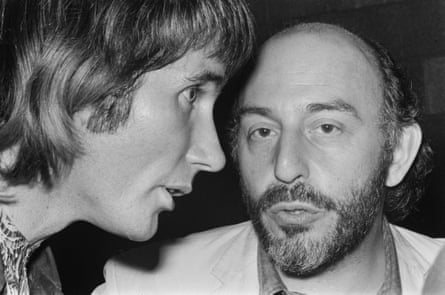

Frank Dunlop, who has died aged 98, never got the credit he deserved during his lifetime. He was a populist pioneer and genuine visionary who created London’s Young Vic theatre from scratch, radically changed the nature of the Edinburgh festival and, at the Brooklyn Academy of Music, tried to introduce institutional permanence to New York theatre. He was also a figure of bustling energy. Even in his 90s, when I would see him on his annual return to Edinburgh, he would be talking about future projects. In fact, he reminded me of a line from a great Latin poet: “Leisure, Catullus, does not agree with you.”

The Young Vic is his enduring legacy but one forgets what an extraordinary achievement it was in 1970. It was a breeze block building created in nine months out of a former butcher’s shop, and was inspired by Dunlop’s memories of the postwar dream of a theatre centre operating under the auspices of the Old Vic. Dunlop’s Young Vic had a similar relation to Olivier’s National Theatre parent company, but it soon established its own identity. Offering lively productions to young audiences at affordable prices, it mixed classics by Shakespeare and Molière with the best of Beckett, Ionesco and Genet.

Nicky Henson, a key member of Dunlop’s team and a fine Jimmy Porter in Look Back in Anger, once told me that the Young Vic company was essentially Dunlop’s surrogate family. I saw the truth of that a few years ago when I got a call from him inviting me to a tea party in Soho to mark a significant Young Vic anniversary. Around the table were original members of the company including Ronald Pickup, Andrew Robertson, Cleo Sylvestre, Anna Carteret and Annabel Leventon. Quite spontaneously people would get up and tell stories of the Young Vic in its early days. Ron Pickup, who had played Oedipus, recalled Olivier coming to see it and telling him afterwards: “Ron, you are a highly promising young actor playing the lead in one of the greatest plays in world drama in the most beautiful new theatre in London. So why the fuck couldn’t I understand a word you were saying?” As Ron told this self-deprecating story, Frank chuckled in the corner like an affectionate father.

Dunlop went on to run the Edinburgh festival from 1984 to 1991, and totally altered its character. Under previous directors, drama had always been a poor relation of classical music and opera, but Frank reversed the roles. He gave us a series of international theatre seasons including visits from Sweden’s Ingmar Bergman, Poland’s Andrzej Wajda, Spain’s Victor Garcia and Germany’s Manfred Wekwerth and Joachim Tenschert. But perhaps his greatest coup, aided by Thelma Holt, was to introduce the Japanese master Yukio Ninagawa to British audiences. I still rate his cherry-blossom Macbeth as one of the most beautiful productions I’ve ever seen, but it was followed by Ninagawa’s equally striking productions of Medea, The Tempest and a contemporary play, Tango at the End of Winter.

Dunlop was more diplomatic with visiting companies than with local politicians, and caused fury with the council when the idea of alternating the festival between Glasgow and Edinburgh was seriously mooted. But for a journalist, he was always good copy – not least when publicly suggesting that the fringe had become “smug and self-satisfied”.

Because he was such an innovator, one forgets that he was also a very good director, and two of his productions reveal his capacity for nursing great performances into being. In 1971, while working for the National Theatre company at the Old Vic, he directed Carl Zuckmayer’s picaresque fable The Captain of Köpenick, which shows a former prisoner acquiring a new persona the second he dons a soldier’s uniform. The play got a great performance from Paul Scofield, whose slack-jointed knees looked as if they could barely support the fragile load they were asked to carry, but it was Dunlop who provided the essential framework.

In 1974 John Wood gave a similarly virtuosic performance in an RSC Sherlock Holmes, but again it was Dunlop who caught the unabashed theatrical vigour of William Gillette’s close-shaven adaptation of Conan Doyle.

There were many other aspects to Dunlop’s varied career: he was the original director of Joseph and the Amazing Technicolour Dreamcoat, the creator of Pop Theatre for whom he staged The Winter’s Tale and The Trojan Women, the man who turned Jim Dale into a Broadway star in Scapino, and who later directed Delphine Seyrig in Antony and Cleopatra. Because of his restless energy and reluctance to stay too long in one place – rather like a modern-day Tyrone Guthrie – Dunlop was undervalued, but if only for the creation of the Young Vic he would demand a permanent place in theatrical history.

.png) 1 month ago

48

1 month ago

48