Nicholas Hytner’s new film, The Choral – in UK cinemas today – culminates in an unconventional rendition of Edward Elgar’s The Dream of Gerontius. Alan Bennett’s screenplay is an affectionate portrayal of a choral society in a small Yorkshire town during the first world war. Searching for non-German repertoire, the chorusmaster Dr Guthrie (Ralph Fiennes) settles in desperation on Gerontius.

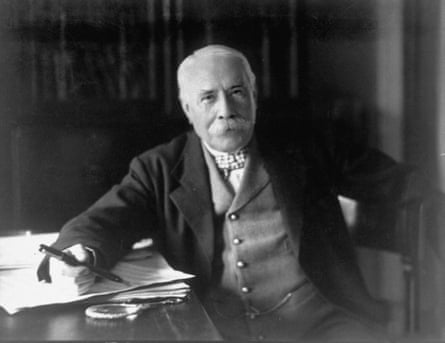

Perhaps it is Elgar’s reputation as a pillar of the British establishment – he appears briefly in the film, a cameo from an extravagantly moustachioed Simon Russell Beale – that reassures Bennett’s fictional committee members that this will be a safe choice. But as Guthrie starts to teach the unfamiliar score, they realise Sir Edward’s patrician persona has deceived them. They expected something staidly English, but instead encounter music they find disturbingly Catholic, foreign and theatrical.

Bennett’s screenplay is full of characteristic whimsy – at one point choir members deliver pitch-perfect renditions of Gerontius as they run through the streets, a scenario the intricacy of Elgar’s choral writing makes difficult to believe – but it is nonetheless rooted in a secure understanding of the work’s troubled and controversial history.

Much of the controversy came from Elgar’s choice of text. John Henry Newman wrote his long narrative poem in 1865, after the conversion to Catholicism that had seismic consequences for him and the Church of England. It depicts an everyman figure (the name “Gerontius” is taken from the Greek word for old man) who passes through the moment of death. He meets an angel who shows him the face of God, before sending him to purgatory with the promise of everlasting glory thereafter. “Not much of a story,” one of Guthrie’s choristers complains – but the requirement to represent the denizens of purgatory, a state not recognised in Protestant theology, proves deeply uncomfortable for many of the choir’s members.

The Catholic Elgar had long wanted to set the poem, but feared, with some justification, that anti-Catholic prejudice would condemn his efforts to failure. The premiere at the triennial 1900 Birmingham festival was beset by ill fortune. The original chorus-master – the magnificently named Charles Swinnerton Heap – died suddenly a few months before the premiere. His replacement, William Stockley, was incompetent and vehemently anti-Catholic and his hostility to the piece, combined with the choristers’ ignorance of Newman’s poem, doomed the premiere to disaster. Even the conductor Hans Richter, one of the era’s most celebrated maestros, seemed ill at ease, perhaps because Elgar was so last-minute with the orchestration that Richter received the full score only shortly before the rehearsals.

The Birmingham choir’s delivery of the complex choral writing was savaged by the critics, and many were lukewarm about the piece itself. The experience rocked the faith of the hitherto devout Elgar: “I have allowed my heart to open once,” he told his friend AJ Jaeger, the “Nimrod” of the Enigma Variations, “it is now shut against every religious feeling.” Prejudice remained in the years that followed. Several Anglican cathedrals agreed to mount Gerontius only on condition that overtly Catholic features of the text, such as prayers to the Virgin Mary, were excised. King Edward VII declined to attend the first London performance because it took place in the Catholic Westminster Cathedral.

But after the disastrous Birmingham premiere, two performances in Düsseldorf salvaged the work’s reputation, and by the end of 1903 Gerontius had been performed, to acclaim, in Chicago, New York and Sydney as well as across the UK. In 1916, the year in which The Choral is set, six performances under Elgar’s baton were given on consecutive nights in London’s Queen’s Hall. The king and Queen Alexandra were among the capacity audiences, and the run raised almost £3,000 for the Red Cross’s war efforts. So, for an amateur choral society in wartime, Gerontius would have been a voguish though admittedly very bold selection.

Elgar’s career at this point was at its zenith. His Ode for Edward VII’s Coronation in 1902 united his already famous Pomp and Circumstance tune with the words “Land of Hope and Glory” and made him indisputably Britain’s best-known composer. In the following years he received a knighthood and numerous honorary doctorates, triumphantly unveiled his long-awaited First Symphony, and succeeded Richter as principal conductor of the newly founded London Symphony Orchestra.

Though Elgar has often been described as quintessentially English, he was better informed about musical developments in continental Europe than most of his contemporaries. And Europe repaid the compliment. Guthrie’s remark to his sceptical choristers that “in Germany Elgar is a God – he’s up there with Wagner” is perhaps a touch hyperbolic, but it reflects the extraordinary esteem in which Elgar was held in Germany after Gerontius’s triumph in Düsseldorf. He was routinely described as the most important English composer since Henry Purcell. Richard Strauss raised a toast at the second Düsseldorf performance to “the first English Progressivist, Meister Edward Elgar”. And the loyal Richter praised him at the opening rehearsal for the First Symphony as “the greatest modern composer – and not only in this country”.

Elgar’s affinity with German music, and with Wagner in particular, ran deep. He and his wife, Alice, regularly visited the festival Wagner had founded in the Bavarian town of Bayreuth; the couple loved Bavaria and felt accepted there, thanks to its predominantly Catholic population. Elgar’s own music was profoundly affected by what he heard in Bayreuth: The Ring, Tristan und Isolde, and in particular Parsifal.

The singers in The Choral are just as thrown by Gerontius’s alien musical language as by its Catholicism. The influence of Wagner’s “stage festival dedication play” can be felt in every aspect of Gerontius: its harmony, its style of vocal declamation, its use of leitmotifs that signify particular themes or ideas, and its architecture: like Parsifal’s acts, the two parts of Gerontius are continuous spans of music rather than divided into separate recitatives, arias and choruses.

This sense of musical continuity, almost unprecedented in a religious work for the concert hall, was one of the reasons that Elgar refused to label Gerontius an “oratorio”, the term generally used for a work for solo singers, choir and orchestra that treats a religious or biblical theme. Though the piece is sometimes described as an oratorio in music history books and programme notes, Elgar himself claimed that “there’s no word invented yet to describe [it]”.

Elgar’s Wagnerism is also evident in Gerontius’s consistently dramatic treatment of its subject matter. The choral singers, no less than the soloists who take on the roles of Gerontius, the Angel, the Priest and the Angel of the Agony, are always called on to represent flesh-and-blood characters, whether friends of the dying Gerontius, demons jealous of his soul’s apparent fast-tracking to paradise, or angels calling from heaven. And the music they are given is sensitive to every nuance of Newman’s text while also evoking the extraordinary visions it describes. Gerontius feels much closer to opera than to the oratorios of Elgar’s immediate English predecessors, with their often formulaic construction and cardboard characterisation.

In The Choral, the singers pursue this observation to its logical conclusion by taking a decision – one that disgusts the fictional Elgar – to stage and costume their performance. Staging Gerontius would not be an entirely outlandish proposition for a professional company – English National Opera mounted a “concert staging” at the Royal Festival Hall in 2017 – but it strains credibility to think that it could have succeeded in the ramshackle circumstances in which the singers in the film are working. Elgar’s music stretches the capabilities of amateur singers to the utmost; it is hard to believe that the singers of 1916 would have had any headspace remaining for acting.

Paradoxically, however, it is here, when the film is least plausible from a musical point of view, that it is most emotionally involving. Gerontius is sung by a young man, Clyde (Jacob Dudman), who has lost his arm in the war. Elgar complains that Gerontius should be an old man, but Clyde tells him it is the young who are dying now, and this is why he is dressed as a soldier. A vicar objects that there is no such place as purgatory; Clyde angrily responds that there is – it is the no man’s land from which he has just returned.

Clyde himself, not just the character he plays, finds solace in the singing of the Angel – represented here by a nurse – and in the powerful image of social cohesion conjured by the coming together of the choral forces for the work’s tender conclusion. This sense of community, as Hytner has pointed out, is all the more poignant because it is shattered only hours after the performance: in the film’s closing shots the lads who had joined the choral to sing the Elgar have been conscripted and leave for the front.

Gerontius undoubtedly transformed British music – it influenced composers such as Vaughan Williams and Walton, and Britten made his admiration clear in heartfelt performances with Peter Pears – but it arguably changed British society too. By allowing Newman’s Catholic theology to be articulated in Anglican cathedrals and widely disseminated, it surely encouraged greater ecumenical understanding. And by offering music of such extraordinary intensity and fervour, Elgar helped explode the myth of Victorian emotional restraint, three months before the queen’s death brought the era to an end.

Today, the work is a performed regularly across the world, and there is no shortage of superb recordings (John Barbirolli’s and Adrian Boult’s interpretations with Dame Janet Baker are legendary; among modern versions, Mark Elder with the Hallé in 2008 and Nicholas Collon with the Finnish Radio Symphony Orchestra, released earlier this year are particularly recommended). There remains a danger, however, that the very familiarity of Gerontius might produce an experience more comfortable than Elgar intended or than Newman’s story warrants. The rough-and-ready account of the work given by the singers in The Choral, for all the film’s comedy, reminds us of Gerontius’s revolutionary potential.

.png) 2 hours ago

3

2 hours ago

3