Released in 2010 and bundled with the Xbox 360, the Kinect looked like the future – for a brief moment, at least. A camera that could detect your gestures and replicate them on-screen in a game, the Kinect allowed players to control video games with their bodies. It was initially a sensation, selling 1m units in its first 10 days; it remains the fastest-selling gaming peripheral ever.

However, a lack of games, unreliable performance and a motion-control market already monopolised by the Nintendo Wii caused enthusiasm for the Kinect to quickly cool. Microsoft released a new version of the Kinect with the Xbox One in 2013, only for it to become an embarrassing flop; the Kinect line was unceremoniously discontinued in 2017. The Guardian reached out to multiple people involved in the development of the peripheral, all of whom declined to comment or did not wish to go on record. Instead, the people keenest to discuss Microsoft’s motion-sensing camera never used it for gaming at all.

Theo Watson is the co-founder of Design I/O, a creative studio specialising in interactive installations – many of which use depth cameras, including the Kinect. “When the Kinect came out, it really was like a dream situation,” he recalls. “We probably have 10+ installations around the world that have Kinects tracking people right now … The gaming use of the Kinect was a blip.”

Watson speaks about the Kinect, which turns 15 this year, with rare relish. (“I cannot stop talking about depth cameras,” he adds. “It’s my passion.”) As part of the collaborative effort OpenKinect, Watson contributed to making Microsoft’s gaming camera open-source, building on the work of Hector “Marcan” Martin. It quickly became apparent that the Kinect would not, as Microsoft had initially hoped, be the future of video games. Instead, it was a gamechanger in other ways: for artists, roboticists and … ghost-hunters.

The Kinect functions on a structured light system, meaning it creates depth data by projecting an infrared dot cloud and reads the deformations in that matrix to discern depth. From this data, its machine learning core was trained to “see” the human body. In games such as Kinect Sports, this allowed the camera to transform the body into a controller. For people making interactive artwork, meanwhile, it cut out much of the programming and busywork necessitated by more basic infrared cameras.

“The best analogy would be like going from black-and-white television to colour,” says Watson. “There was just this whole extra world that opened up for us.” Though high-powered depth cameras had existed before, retailing at about $6,000 (£4,740), Microsoft condensed that into a robust, lightweight device costing $150 (£118).

Robotocists were also grateful for an accessible sensor to grant their creations vision and movement. “Before it, only planar 2D Lidar information was available to detect obstacles and map environments,” says Walter Lucetti, a senior software engineer at Stereolabs, which is soon to release the latest version of its advanced depth-sensing cameras and software. The 2D Lidar detects objects by projecting a laser and measuring the time the light takes to reflect back; the Kinect, however, could create a detailed and accurate depth map that provided more information on what the obstaclemay be and how to navigate it. “Before Kinect-like sensors,” Lucetti says, “a tuft of grass was not perceived differently from a rock, with all the consequences that entails for navigation.”

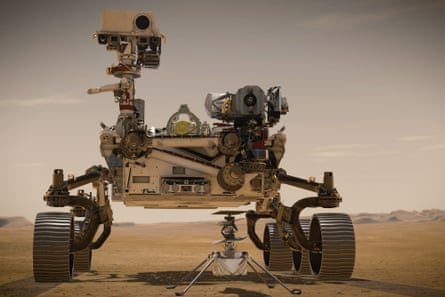

This type of depth camera now powers a host of autonomous robotics, including 2020’s Perseverance Mars Rover’s AutoNav system, and Apple’s facial identification tech. (Apple bought PrimeSense, the Israeli company behind the Kinect’s structured light system, in 2013.)

The Kinect’s technology was soon eclipsed by freely available open-source sensors and more advanced motion-sensing devices. But since Microsoft ceased manufacture of the Kinect line in 2017, the little camera has enjoyed a spirited and not entirely un-troubled afterlife. It has watched over the Korean demilitarised zone and worked on topography and patient alignment in CT scanners; reports have emerged of it being used in airport baggage halls, as a security camera in Newark Liberty International airport’s Terminal C (United Airlines declined to comment on this), and even to gamify training for the US military. It’s been attached to drones, rescue robots and even found a brief application in pornography.

“I’m not sure anyone had a firm vision of what interactive sex involving the Kinect would be,” says Kyle Machulis, founder of buttplug.io and another member of the OpenKinect team. The camera was deployed mostly as an over-complex controller for 3D sex games, fulfilling “more of a futurist marketing role than anything of actual consumer use,” Machulis says. In that role, it was successful: it attracted a flurry of attention, and threats from Microsoft to somehow ban porn involving Kinect. It was an interesting experiment, but it turned out that the addition of a novelty device was not a turn-on for many porn users. Besides, as Machulis says, when the camera malfunctions, “it looks pretty horrible.”

after newsletter promotion

Unreliability is of less concern for ghost hunters, who thrive on the ambiguity of ageing technology and who have rebranded the Kinect as the “SLS” (structured light sensor) camera. They deploy its body tracking to find figures the naked eye cannot see. Ghost hunters are thrilled by the Kinect’s habit of “seeing” bodies that aren’t really there, believing that these skeletal stick figures are representations of disembodied spirits.

The paranormal investigation industry doesn’t care much about false positives, so long as those false positives can be perceived as paranormal – which is just as well, says Jon Wood, a freelance science performer who has a show devoted to examining ghost hunting technology. “It’s quite normal for ghost hunters to be filming themselves in the dark, with infrared cameras and torches. You’re bathing the scene with IR light, while using a sensor that measures a specific pattern of infrared dots,” he says. Given that Kinect is designed specifically to recognise the human body in any data it receives, it would be stranger if the Kinect didn’t pick up anomalous figures in this context.

There’s a certain poetry in the Kinect living on among those searching for proof of life after death. In the right hands, the camera is still going strong. Theo Watson points me in the direction of Connected Worlds, an exhibition that has run in the New York Hall of Science since 2015. Of the many Kinect devices that power the installations, only two have had to be replaced in the decade since it opened – and one of those was only a few weeks ago. Watson started stockpiling the device when Microsoft ceased production.

“Half the projects on our website wouldn’t exist without the Kinect,” he says. “If we had this camera for another decade, we would still not run out of things to do with it.”

.png) 8 hours ago

4

8 hours ago

4