In autumn 2003, about six months after Britain invaded Iraq, Paul Mace had a thought: what if we put poppies on football shirts? Mace, who was then executive director of Leicester City, had always felt strongly about the annual poppy appeal – his father had served in the second world war – and this, he hoped, would bring it to another level.

After securing permission from the Premier League, Mace had to find someone to design and manufacture an embroidered poppy patch for the shirts. Poppies in the UK are supplied by a charity, the Royal British Legion (RBL), to raise funds for ex-service personnel in need, but since the RBL didn’t produce patches, Mace arranged to auction off the shirts afterwards and donate the funds.

The first match where Leicester’s strip would feature poppies was a week before Remembrance Sunday, against Blackburn Rovers. It was going to be aired live on Sky Sports, and it struck Mace that if only one team was wearing poppies, the other team would look bad. “We didn’t want a situation where we had ourselves as a club on TV wearing poppies, showing up the other team,” he told me, his slightly incredulous tone indicating how outrageous this would have been. Blackburn hastily commissioned its own poppy patches.

The match was the first time remembrance poppies had been worn by all the players in a Premier League game. “I don’t think I ever heard a single complaint, and universal praise is very rare in football,” said Mace. He was proud to see veterans parading on the pitch at half-time, proud of the positive press coverage and proud to raise more than £5,000 for the RBL. “If I look back on 13 years at Leicester, this was probably the best decision I ever made,” he said.

After the matches, other clubs contacted Mace. “They had questions: where did you source the embroidered poppies? What permissions do we need?” Over the next few years, the Premier League granted permission to any club that wanted to wear poppies, but didn’t impose rules about whether they should. That would come later. Within a few years, as the presence of poppies on football shirts was enforced ever-more hawkishly by the press and politicians, it would be hard to remember that for 82 years, no football team had played with poppies on their shirts and absolutely no one had suggested that there was any problem with this.

Remembrance poppies have been worn in Britain since 1921, to commemorate soldiers killed in action. Originally worn on shirt lapels for a single day, 11 November, Armistice Day, they’re now typically worn for more than a fortnight and they appear everywhere – not just pinned on clothing but wrapped around buses and trains, projected on monuments and power stations, even sprayed on to grass verges and knitted on postboxes.

The poppy has two purposes: collective remembrance for the war dead and fundraising for the RBL. Last year, the poppy appeal brought in more than £49m, which goes towards supporting former and current members of the armed forces and their families, with anything from psychological help to legal costs. “If you’ve served, we’ll provide support for the rest of your life whenever you need it,” said Philippa Rawlinson, director of remembrance at the RBL. “That’s what we’re here to do.”

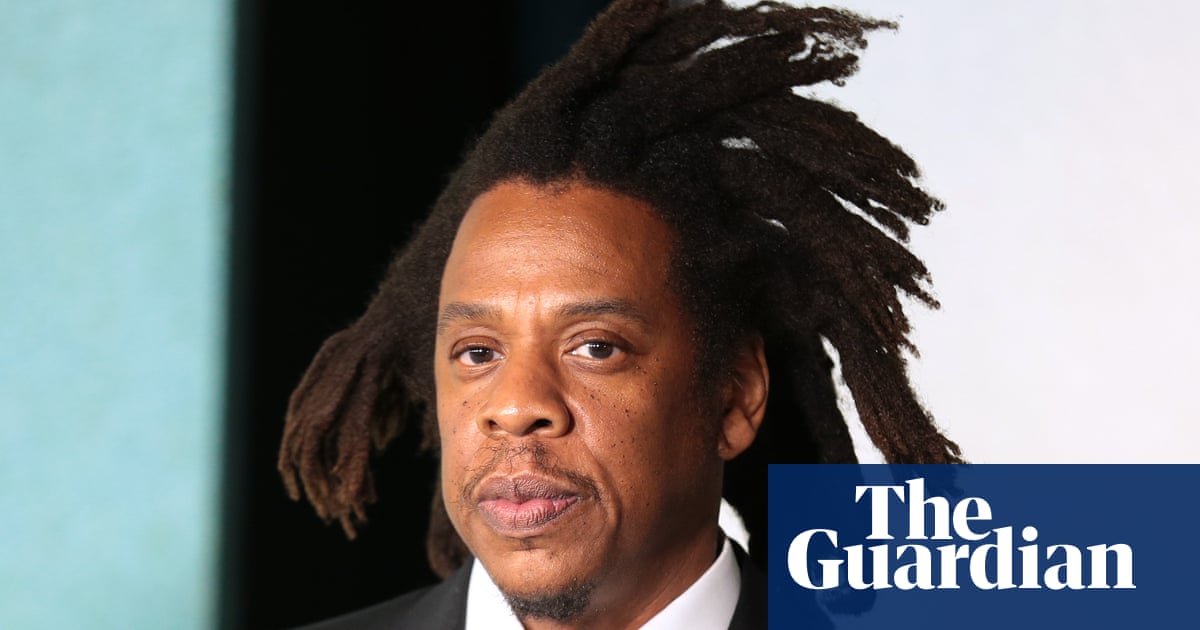

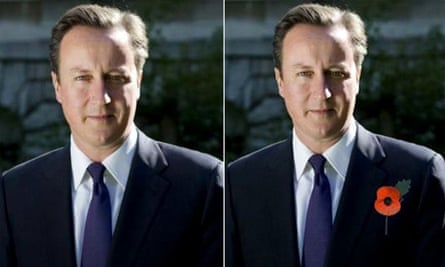

But as anyone living in Britain knows, the poppy is much more than a fundraiser. Over the past 20 years, poppies have boomed, with ever-more flamboyant displays, including a three-metre poppy hung on Antony Gormley’s monumental sculpture the Angel of the North and a fibreglass poppy, the largest yet, five metres in diameter, which looms over the concourse at King’s Cross station. Once a modest sign of remembrance, the poppy has increasingly been used as a prop for performative patriotism, and a way to gauge others’ loyalty to an ideal of national sacrifice. In 2010, then prime minister David Cameron and a team of ministers insisted on wearing poppies during a state visit to China, even though Chinese officials asked them not to because the poppy is a symbol of China’s humiliation in the 19th-century Opium wars. (“We informed them that they mean a great deal to us and we would be wearing them all the same,” an unbending British official told journalists.) Public figures who appear without a poppy in November quickly find themselves attacked by social media trolls and the tabloids.

This is profoundly uncomfortable for the RBL, the charity at the heart of the Poppy Appeal. “If anyone doesn’t want to wear a poppy, we’re on their side. It has to be a personal choice or it loses its meaning,” said Rawlinson. “But although we produce the poppy, we don’t own it as such, it belongs to the nation.” As the symbol has proliferated, it has taken on a life of its own, becoming a stand-in for a host of other conversations, about patriotism, national pride and the nebulous question of what it means to be British.

On a wet September day, the former soldier Davy Adamson met me at the door of Lady Haig’s Poppy Factory in Edinburgh to give me a tour. Established in 1926 to give work to disabled veterans, the factory today is still staffed entirely by ex-service people. Until a couple of years ago, they handmade the 2 million poppies distributed in Scotland each year. When this work was automated, the veterans switched to hand-making poppy wreaths, to be laid at the foot of memorials around the country. When I visited, they had started work on the 30,000 wreaths on order for 2025.

The factory doubles as a museum, with a roaring trade in school visits. Adamson, who has worked here for more than a decade, led me down a long corridor towards the factory, decorated with words from the poem In Flanders Fields, written in 1915 by John McCrae, a Canadian medic and lieutenant colonel, which ends with the lines: “If ye break faith with us who die / We shall not sleep, though poppies grow / In Flanders’ Fields.”

More than 880,000 British soldiers – 6% of the male population – had been killed in the Great War, and the almost 2 million wounded returned home to find that little provision had been made for them. In 1921, Earl Haig founded the British Legion to support returning veterans and their families. Inspired by similar campaigns in the US, Canada and France, Britain’s first Poppy Day was organised for 11 November of that year. It was a huge success; the 9m poppies produced sold out, and Poppy Day became an annual event, as did a remembrance ceremony at the Cenotaph and a two-minute silence at 11am on 11 November.

Some veterans preferred to celebrate their victory in a less solemn manner, and throughout the 1920s, Armistice Day balls were held, which were fairly drunken and riotous affairs. As the decade wore on, the balls were attacked in the press and gradually died out. Meanwhile, other veterans protested that they had been abandoned by the country they had fought for. On 11 November 1922, a group of unemployed ex-servicemen marched to the Cenotaph wearing pawn shop receipts pinned to their jackets next to their medals.

Today, poppy production and distribution largely takes place at the RBL’s factory in Aylesford, about 40 miles from London. In late September, Lucy Inskip, director of the Poppy Appeal, showed me around. “It’s our busiest time of year,” she yelled over the sound of machinery, gesturing to the cardboard boxes of poppies and commemorative wreaths stacked 6ft high on pallets. In a room adjacent to the main warehouse, two compact machines churned out the nation’s poppies. Two large spools of paper – one red, one green – fed into each machine. In a hypnotic motion, metal arms sliced them into red petals and green stems, then stamped the two pieces together with a black whorl. Over the course of a year, 4.5 miles of paper are transformed into 30m poppies, shipped to volunteers around the country.

The RBL tries to distinguish between honouring soldiers and glorifying war. “We’re giving thanks while hoping for a peaceful future,” said Rawlinson. But this is a fine line to maintain, particularly as politicians try to rally support for the military in times of war. “Throughout the cold war, as big anniversaries of D-day and so on passed, the poppy was positioned as ‘the western allies fought and died for freedom, and they’re willing to do it again now’,” said Lucy Noakes, a historian at the University of Essex. “That’s not really gone away.”

White poppies, first produced in 1934 by the Peace Pledge Union as a pacifist symbol to commemorate military and civilian victims of war, are often met with powerful disapproval. Margaret Thatcher expressed “deep distaste” at white poppies being worn at Remembrance events. More recently, former Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn was criticised for wearing one, and white poppy wreaths have been removed from war memorials.

War is boom-time for poppy sales. In 1982, the year Britain went to war in the Falkland Islands, the Poppy Appeal recorded its highest-ever takings. “Soldiers were coming back injured, and refusing to wear a poppy looked like refusing to support ‘our boys’,” said Charlotte Lydia Riley, a historian at the University of Southampton. “From that moment, you had a very charged sense of what patriotism means.”

As strong feelings provoked by the Falklands War died down, so did the imperative to wear a poppy. But behind the symbolism, there was still a charity that needed to raise money. In 1997, the RBL hired a PR firm, which organised a glitzy launch event featuring the Spice Girls and the iconic wartime singer Vera Lynn. It had an effect; £17.3m was raised that year, up £1.2m from the previous year. But it was when Britain went to war again – first in Afghanistan in 2001 and then in Iraq in 2003 – that the poppy really entered a new era.

As the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan rolled on, new advocacy groups like Help for Heroes placed the attention on wounded and traumatised veterans receiving insufficient government support. Poppies took on a political potency. In 2006, Gordon Brown proposed that Remembrance Sunday should be developed into a national day of patriotism, similar to the Fourth of July in the US.

The following year, the deaths of British soldiers entered the public consciousness in a new way. Until then, casualties from Iraq and Afghanistan had been quietly repatriated via an RAF base in Oxfordshire, but in April 2007, when that airstrip was closed for resurfacing, flights bringing the military dead were rerouted to a base in Wiltshire. Convoys leaving the airfield carrying soldiers’ coffins had to pass through the town of Wootton Bassett. As the first cortege drove slowly by, the coffins draped in union jacks, people spontaneously lined the streets to pay their respects. This quickly became a new public ritual, attracting hundreds of people and wide media coverage. Everyone I spoke to involved with the Poppy Appeal mentioned how crucial Wootton Bassett had been in renewing sympathy for the armed forces. The Poppy Appeal saw its biggest ever jump in donations in 2007, raising £30.4m, an increase of £4.4m on the previous year.

As support for the armed forces intensified, so too did pressure to show it. In 2003, when the presenter Jonathan Ross forgot to wear one while recording a show about cinema, panicked producers superimposed a digital poppy in post-production. On screen, the digital poppy danced around, occasionally floating free of the suit. In 2006, Channel 4 received a deluge of complaints about the newsreader Jon Snow for his lack of a poppy in the studio. Snow responded with a written statement: “There is a rather unpleasant breed of poppy fascism out there – ‘he damned well must wear a poppy!’ Well I do, in my private life, but I am not going to wear it or any other symbol on air.” But Snow’s response did not change the tide, and in the years that followed, poppymania would only grow.

By 2009, six years had passed since Mace put poppies on Leicester City’s shirts. That year, Charles Sale, a sports writer for the Daily Mail, was chatting to a Premier League contact who mentioned that 12 out of 20 teams in the league now wore poppies on their shirts. Sale didn’t have strong feelings about poppies; what he did have was pages that needed to be filled. “I’m not a mad patriot,” he told me. “But I had to find a story every day.”

Sale wrote up the column about the poppy holdouts. Senior editors loved it and decided to launch a campaign to ensure that no team would remain poppyless. They called it Poppygate. “The first rule of a Daily Mail campaign is you don’t start a campaign that you’re not going to win,” a former editor who worked with Sale told me. “We knew it would resonate with our audience, this idea of the military and the need to show respect.”

Over the next few days, the Daily Mail went hard, calling out teams who didn’t wear poppies. “I worked at the Daily Mail for 20 years – shaming people was part of the process,” said Sale. Six teams quickly bowed to the pressure and ordered their poppy patches. “That was the power of the Mail at the time,” said Sale. Liverpool and Manchester United resisted, arguing that poppies wouldn’t show up on their red shirts, and that it wouldn’t add to the substantial work they already did with the armed forces. (A news story that week thundered that this “excuse” was “undermined by the emblem being proudly displayed on the red shirts of Arsenal.”) The following year, both teams wore poppies.

From then on, poppy shaming became an annual tradition as November approached. “We’d think: who’s playing? Are they wearing poppies? What are they doing to commemorate?” said Sale. In 2011, a story came along so perfect that it felt almost scripted. England were due to play a friendly match against Spain on Armistice Day, and Fifa, world football’s governing body, refused to allow England to wear poppies on their shirts. “It was a great story for us: how dare we not do our boys proud by honouring them with the poppy, just because it might upset the Europeans?” remembered the former Daily Mail editor. (In truth, it was not a matter of overly sensitive Europeans: Fifa has a longstanding prohibition on political symbols on football shirts.)

The story was picked up everywhere. Prime minister David Cameron described the ban as “outrageous”, adding: “We all wear the poppy with pride, even if we don’t approve of the wars people were fighting in.” Prince William, who was then president of the FA, wrote to Fifa expressing “dismay” at the decision. Two members of the English Defence League, a far-right group, climbed on top of Fifa’s Zurich headquarters and photographed each other holding a banner that said “How dare Fifa disrespect our war dead and wounded”. Fifa did not budge; the match went ahead without poppies, though there was a two-minute silence before kick off. (The organisation eventually lifted the ban in 2017.) “That Fifa ban in 2011 was a moment where we realised poppies would give us a lot of mileage,” one former Sun reporter told me. “And year after year, that has proven to be true, not just in sports.”

Dissenters were pilloried. When the Northern Irish footballer James McClean chose not to wear a poppy, because of the role of the British army in the Troubles, he received death threats. McClean’s decision not to wear the poppy has defined his career, at least in the eyes of the public, and he continues to be the target of sectarian chants and abuse.

In the past two decades, numerous people have been arrested for setting fire to poppies, with charges ranging from public order offences to incitement to hatred. In 2012, a 19-year-old who posted a photo of a burning poppy on Facebook with the caption “take that squadey [sic] cunts” was arrested. Subsequent media coverage provoked such fury that he had to be relocated for his own protection. Last year, a number of stories about poppy sellers allegedly being attacked and intimidated by pro-Palestine protesters appeared in the press. (“Where have all the poppies gone?” said a Sun headline, while the Mail said some sellers were “terrified to go out”.) British Transport Police said these reports were “misleading”, and the RBL said it had heard of no unusual reports of abuse. But the incident demonstrated the subtext, so often present in discussions of the poppy: threats to a particular notion of Britishness and threats to the poppy are seen as one and the same.

As the centenary of the first world war approached, the pressure was on to take commemoration to new heights. Ceramic poppies, glazed bright red, started to appear in the moat of the Tower of London in July 2014. Over the following months, the moat was filled until it looked like it was flowing with blood. By November, 888,246 poppies spilled over its edges, matching the number of Britons killed in the first world war. Later, the ceramic poppies were sold to raise money for the RBL. The installation, by artists Paul Cummins and Tom Piper, gained near universal acclaim, although the Guardian’s critic Jonathan Jones described it as a “deeply aestheticised, prettified and toothless war memorial”, arguing that the symbolic red flower obfuscated the true horror of war. (MailOnline responded to the review with an article headlined “Why DO the Left despise patriotism? Sneering Left-wing art critic brands the poppy tribute seen by millions at the Tower as a ‘Ukip-type memorial’.”)

The 2014 centenary commemorations were a huge success, but when Gordon Michie took the job of running the annual Poppy Appeal in Scotland in 2016, he was concerned about waning interest. “There was an assumption there would be poppy fatigue, and that with no one still alive from the first world war people would want to move on,” Michie told me. He need not have worried. Instead, the centenary heralded a poppy boom, and this was sustained by the iron law of public commemoration – once a new commemorative act has been introduced, it looks disrespectful not to keep doing it.

The solemnity of remembering those who have died in action is often at odds with the proliferation of poppy-related merch. Poppies and the phrase “Lest we forget” have appeared on everything from shot glasses to thongs. “It’s become a bit like Halloween, hasn’t it?” said Sale. The great chronicler of this frenzied poppymania is the X account @GiantPoppyWatch, which launched in 2016 and has 74,000 followers. It collated pictures of inadvertently comic poppy displays: pizzas with pepperoni arranged like poppy petals (“Nothing gets you in the RembrancingSeason spirit quite like the mouthwatering aroma of a freshly baked PoignantPoppy&PepperoniPizza!”) and poppy trainers (“poignant-but-smart blood-red”). (The creator of the account stressed that “Poppy Watch is a showcase of the insincere” and he was not aiming to mock “little old ladies or guys who’ve got poppy tattoos for the mates they lost in Afghanistan”.)

As disproportionate displays became more commonplace, so did the hounding of public figures. Since 2013, the ITV newsreader Charlene White has been subject to an annual deluge of racist and sexist abuse for not wearing a poppy on air. When I asked White for an interview, her representative replied: “Charlene doesn’t give interviews about her poppy decision as this has led to online trolling and abuse.”

The fear of being caught without a poppy can lead to rash decisions. In 2015, a Twitter user noticed that a Facebook photograph of then prime minister David Cameron had been altered, with a poppy superimposed on to his suit. (“Now with added patriotism,” read one tweet.) At the peak of centenary poppy fervour in November 2016, the Cookie Monster – a character from Sesame Street, “essentially a blue rug with ping pong ball eyes” according to one viewer – appeared on The One Show, a BBC chatshow, with a red poppy pinned to its blue fur. Sitting alongside him, another guest, Chris Tarrant (poppy present and correct) gamely attempted to feed the furry puppet with cookies as the hosts (also wearing poppies) gabbled away. @GiantPoppyWatch tweeted stills of the show with the caption “ME REMEMBER FALLEN”. Comedian Dara Ó Briain tweeted: “I am choosing to regard this as satire and thus genius.”

Pinning a poppy on the Cookie Monster is, of course, absurd. One major reason hapless BBC staff did so was that they were terrified of getting in trouble with the Daily Mail, which had spent years furiously insisting that everyone from X Factor judges to comedy panellists wear poppies. Like a courtier who, in desperately seeking to please a tyrannical king, ends up abasing himself and annoying their ruler, the decision backfired. The Mail thundered that pinning a poppy on the Cookie Monster was “disgraceful” and BBC staff were “trivialising the sacrifice of millions”.

I spoke to several former BBC employees who all laughed about this incident, but expressed sympathy for programme staff who would have made a split-second decision. “I can 100% see how that happened,” said one BBC producer. “The atmosphere in November is always ‘shit! Where’s my poppy!’ You don’t want to be the person that fucks it up by not providing a poppy. If you forget, it’s kind of your fault if on-screen talent get criticised for being disrespectful.” Signs are regularly affixed to studio doors reminding staff “DON’T FORGET YOUR POPPY”.

Every year, the RBL tries to counter the idea that people must wear a poppy – sending spokespeople out to defend public figures’ right to choose, posting on social media to distance themselves from pile-ons. “When you see criticism on social media, people might think they’re supporting us, but that’s not what the poppy stands for – the whole point of it is freedom and personal choice,” said Rawlinson, of the RBL.

The work of the RBL, meanwhile, continues to be essential. On 24 October, the 2024 poppy appeal launched, this year highlighting the mental scars of conflict. At an emotional breakfast event in central London, veterans talked about their experience of PTSD and depression. “I was a ticking timebomb,” said Iraq veteran Baz Seymour, who suffers from complex PTSD. These moving personal testimonies felt far removed from the self-righteous defence of Britain’s honour as represented (for some) by the poppy.

The Oxford historian Adrian Gregory has written that “As the survivors and immediate family members of the first world war generation have died, followed by those of the second world war, the ceremonies have become related in the public mind less to individual grief and more to ‘national pride’.” Lucy Noakes, the University of Essex historian, pointed out another consequences of this: “As the veterans of the two World Wars die, they’re not here to give their complex or nuanced perspectives.”

The last surviving first world war veteran Harry Patch, who died in 2009, didn’t feel much connection to Remembrance Sunday. It’s “just show business”, he wrote in his memoir. His personal Remembrance Day, he wrote, was 22 September 1917, “the day I lost my pals”.

.png) 2 months ago

14

2 months ago

14