Zdeněk Liška became one of the eastern bloc’s pioneers of electroacoustic music by accident. After breaking through making music for ads and animations, the revolutionary film-makers of the 1960s Czechoslovak new wave asked him to soundtrack their movies, which he took as his greatest inspirations. With the help of radio engineering enthusiasts at Czechoslovakia’s film powerhouse, Barrandov Studios, he could imitate the whoosh of a spaceship or birds chirping. He composed underwater electroacoustic symphonies and music to be played on typewriters. Despite his innovations, he famously proclaimed: “I only write music under the pictures.”

Liška was as productive as he was innovative: from the late 1950s to the late 1970s, he would score eight feature films a year, as well as numerous shorts and TV series. He could go camp or avant garde, channel Disney-like beauty and loved a waltz. His peers recall him composing on the night train or sketching the next cue while the orchestra was still recording the last one. Czechs from across the generations can whistle some of his melodies, such as the carnival-style theme from crime series The Sinful People of Prague.

The longer he worked, the more he saw things in these films that their directors hadn’t even noticed. Liška scored 10 of surrealist director Jan Švankmajer’s short films. “He didn’t attempt to go with the mood of the film,” the director once said. “He was able to discover rhythms that even directors weren’t aware of.” Liška would compose with a stopwatch at the editing table, and often took on the additional role of film editor, suggesting cuts to fit his music. No other musical figure could match his influence on the Czech socialist film industry.

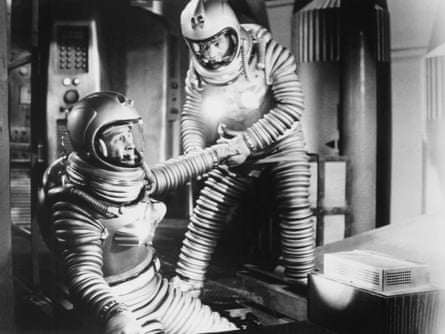

Finders Keepers label head Andy Votel first discovered Liška through the Czechoslovak new wave, and later rereleased his scores for Ikarie XB-1 and The Little Mermaid. He likens his impact to that of Ennio Morricone. “He was solely committed to the film score medium and should be credited as someone who revolutionised how film music is made, despite his music being behind politically landlocked,” he says. He also sees parallels between Liška and electronic music pioneer Daphne Oram: “They were here to communicate with emotion and humour. The process was merely a vessel. But in Liška’s case, the history books, via the setbacks of socialist secrecy, are in need of a remix.”

When Liška died of complications resulting from diabetes in 1983, aged just 61, his work had been almost forgotten. During his lifetime, only two records of his music – including his score for the 1965 Oscar-winning movie The Shop on the Main Street – were released. He wasn’t interested in live concert presentations, believing the sound shouldn’t be disconnected from the vision. He also produced communist propaganda, which complicated his legacy for Czechs.

More than 40 years later, archivists and composers have been restoring his reputation. His music has been staged live on numerous occasions, including by the Prague Symphony Orchestra. Scholars study his electroacoustic inventions, his famous editing table is on display at the Czech Museum of Music and a 2017 Czech documentary, Music by Zdeněk Liška, told younger Czechs his story and underscored the reverence in which he is held. Last year, the Czech label Animal Music launched an archival vinyl series of Liška’s work, promising to open up his archive and release a new album every year. The first was dedicated to his collaborations with Švankmajer; the second, Music to Films by František Vláčil, arrives this month.

Petr Ostrouchov is the label’s curator and composer. Compiling these releases has been a challenge that entails trying to get inside Liška’s head. “Thanks to the trust of the family, I was able to study his sheet music and understand his compositional logic a bit better,” he says. “Later, I was entrusted with access to his personal archive, and I retrieved digitised tapes from an old computer sitting in one recording studio’s cellar in Prague.” For each volume, Ostrouchov digs unnamed files from the hard drive and compares them with the film and sheet music. “A bit of detective work,” he says.

Liška was born to a mining family in central Bohemia in 1922. His father led the miners’ brass band, giving Liška a close connection to music (and inspiring the countless brass motifs in his scores). After the second world war, he began his career at the Baťa shoe factory and its film studios in Zlín, far from his home town, where he composed music for commercials. (The studios were originally founded as the factory’s marketing department, but after the company was nationalised by communists and the city renamed to Gottwaldov, it continued separately as a counterpart to Barrandov.) Liška honed his craft on puppet stories by Hermína Týrlová, a Czech animation film pioneer, and befriended her then assistant, Karel Zeman, whose steampunk style can be seen in the craft of Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton.

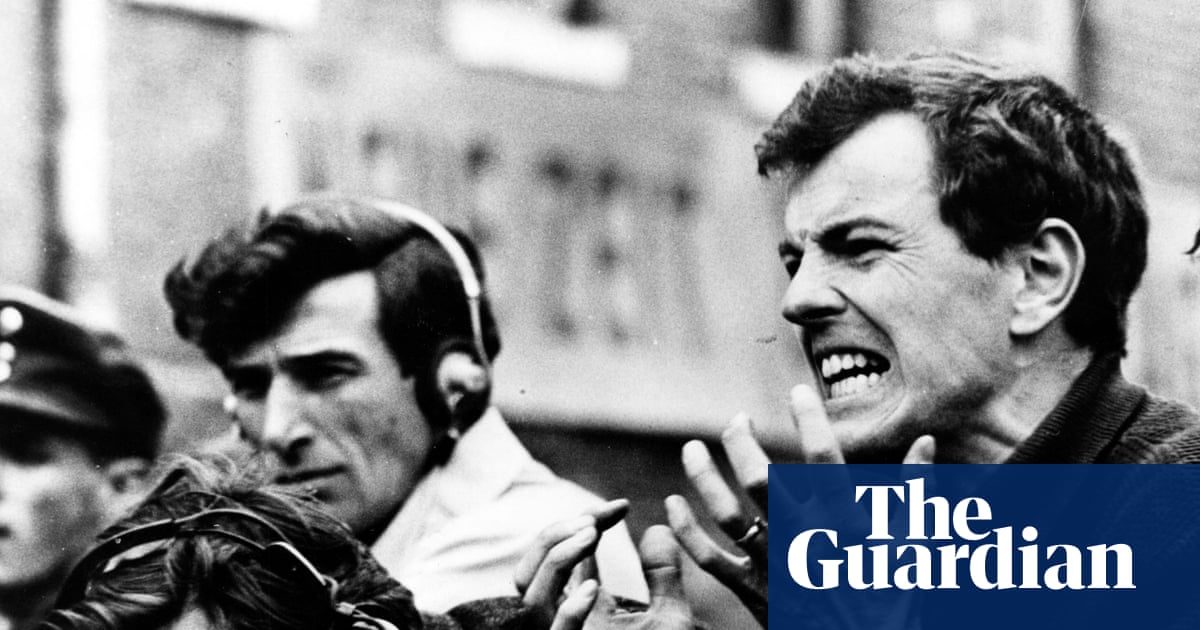

After the award-winning success of Zeman’s adaptation of Jules Verne’s Invention for Destruction, Liška became Czechoslovakia’s number one film composer, in demand by the likes of Věra Chytilová and Juraj Herz. The government also took notice. During the Normalisation after 1968, when four Warsaw Pact countries jointly invaded the country, Liška composed a symphony celebrating the Persian empire for Iran’s Shah Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, and scored the TV detective series 30 Cases of Major Zeman, a propagandist project overseen by the communist ministry of the interior. But he never joined the party or any artistic union. As a composer, he didn’t feel the same pressure as directors or writers.

“I think he was neutral to the regime,” says Liška’s oldest daughter, Hana. “He composed no matter the political system, and he was left to do his job, because his music was an important export and brought significant money back.” (The state agency Art Centrum arranged for him to work on multiple international expos, among other jobs for western countries. Liška also soundtracked expos in Montreal, Canada, and Osaka in Japan.) Prague Symphony Orchestra programme director and longstanding Liška scholar Martin Rudovský suggests that he was a “conformist”, albeit one who “doubted, in private, some of the propaganda films or TV series he scored. Certainly, he was not in opposition, for instance, as composers like Jan Novák.”

Liška was making capitalist money in communist times, which attracted the attention of the politburo, but Liška was too successful to be persecuted. “Having a microwave or washing machine – let alone a swimming pool – was an unimaginable luxury for many at the time,” his daughter Barbora remembers. But not for Liška’s family. “We were used to these odd things.”

At the end of Liška’s life, his daughters remember him spending “more time between hospitals and the recording studio than anywhere else”, until his death in July 1983. His legacy trickled through the iron curtain. Julian House – Ghost Box Records co-founder and then art student – had his first encounter with Liška when the Brothers Quay’s 1984 stop-motion short film The Cabinet of Jan Švankmajer, a surrealist tribute to the director that featured Liška’s music, was shown in the UK. “Liška’s compositions seem to have strange angles; they fit together in an odd way,” he says. House is also a graphic designer: “Something about them reminds me of collage, similarly to the film posters of the Czech new wave.”

When the Berlin Wall came down, Oscar-winning film editor Joe Walker, a close collaborator of Denis Villeneuve, started noticing Liška’s name attached to many extraordinary films, he says. “It became, for me, a guarantee of quality. For a few years, when the editing work I hoped for was out of reach, I wrote music for documentaries, dramas and lots of children’s programmes. I tried to honour Liška every day by providing a diet of good music – serving up advanced harmony and jagged rhythms – even when the images were relatively banal.”

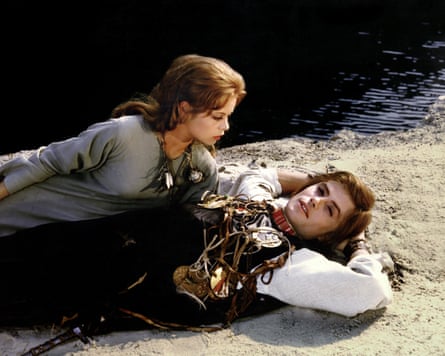

Animal Music’s newest archival volume presents two lesser-known scores from Liška’s late career, collaborations with director František Vláčil. It’s personal for the curator, Ostrouchov: Vláčil’s 1967 existential medieval tale Markéta Lazarová introduced him to Liška in the early 1990s, when the movie won a critics’ poll for the greatest Czech movie of the century. Liška’s darkly ambient score pairs monumental choral music with tape manipulations and distant screams and whispers. (It’s so epic and timeless that the contemporary Czech post-hardcore band Lvmen have sampled bits of the score on every one of their albums since 1999, bringing Liška’s legacy into punk venues.) His score for Vláčil’s 1976 Smoke on the Potato Fields is the complete opposite, using melancholic string arrangements to tenderly guide the narrative about an émigré doctor who returns home in his twilight years.

The archive still presents a gargantuan task for the future: Ostrouchov is imagining albums focusing on Liška’s music for documentaries or children’s programmes. His dream is to release Liška’s score to the questionable detective series 30 Cases of Major Zeman. “Liška scored a lot of schlock, but on the musical side, it was always ingenious,” he says. “He never phoned in.”

.png) 1 month ago

36

1 month ago

36