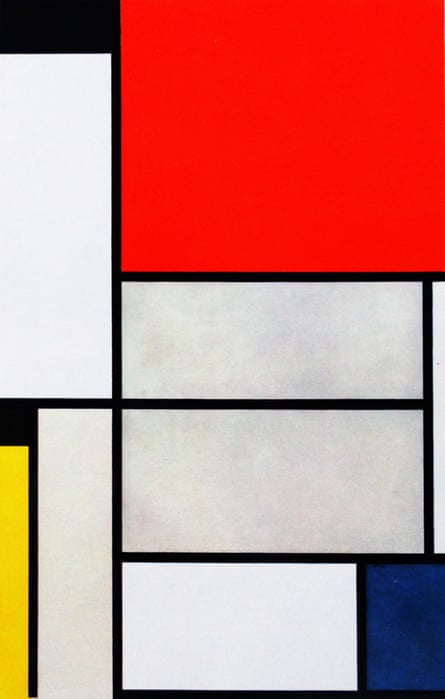

In 1972, the mighty Kunstmuseum in the Hague bought three paintings by a little known British artist called Marlow Moss. The prestigious art gallery was keen to show the enormous influence of Piet Mondrian – the famous Dutch painter acclaimed for his black grids lit with bold blues and brash yellows – on such lowly also-rans as Moss.

Yet, should you visit the Kunstmuseum today, you’ll find the Moss works positioned front and centre, while a similar piece by the great Mondrian, who would later become the toast of New York, is hidden behind a pillar. Why the volte-face? Because it is now widely recognised in the art world that it was as much Moss who influenced Mondrian as the other way round, at least when it came to the double or parallel lines he started using in the 1930s to add tension to his harmonious abstract paintings, one of which hammered last May for $48m.

Seven decades after her death in Cornwall at the age of 69, Moss is enjoying a major revival and reappraisal. As well as the current exhibition of her paintings and sketches in the Kunstmuseum, her sculpture will go on show at the Georg Kolbe Museum in Berlin in April. Last year, meanwhile, her 1944 work White, Black, Blue and Red fetched £609,000 at Sotheby’s in London, double its estimate and a record for her work at auction. Not quite in Mondrian territory, not yet anyway.

It’s an extraordinary turnaround for an artist who was shunned by much of the art world in her lifetime. The Tate wasn’t interested in her. When Moss moved to Cornwall, settling in the beautiful and remote Lamorna Cove near Penzance, she made repeated efforts to contact sculptor Barbara Hepworth and her painter husband Ben Nicholson. They ignored her.

“Moss’s time has come,” says Florette Dijkstra, author of The Leap into the Light, a biography recently published in Dutch. “Art history is a strange science. The landscape can totally shift. The buzzwords today are inclusivity and diversity. Women artists are being promoted, as well as queer artists. This explains – partly – why Moss is getting so much attention.”

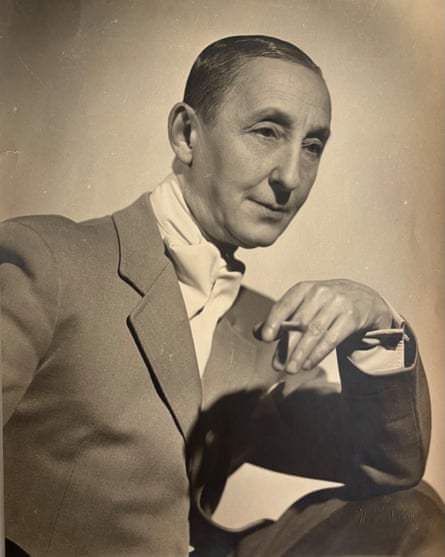

Marjorie Jewel Moss, as she was first named, was born in London in 1889. Drawn initially to dance and music, she went on to study art before moving to Cornwall, where she cut her hair short and changed her name to the gender-neutral Marlow, though was still known as “she”. In the late 1920s, Moss moved to Paris, where she became part of the avant garde scene and a member of the Abstraction-Creation group, which favoured abstraction over figurative work or surrealism.

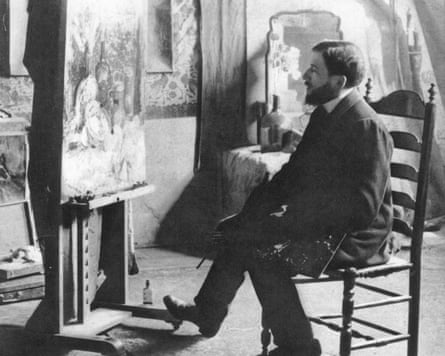

Her entry into the group came via an early admirer, Mondrian, who was a few years her senior and Dutch. Moss had been introduced to him by her partner Netty Nijhoff, a writer from Zeeland. Moss and Nijhoff had met at the Cafe de Flore in Paris. When Nijhoff asked her son to take a note to the lady at the nearby table, the boy asked: “What lady?” Moss was, as usual, in male attire. After they became a couple, both would go about Paris in men’s suits and hats. Nijhoff remained married to her husband, the Dutch poet Martinus Nijhoff, for years to come, though both had other lovers. At times, Moss and Nijhoff had other partners as well.

The reaction this unusual pair prompted wasn’t straightforward, says Dijkstra, even in the so-called liberal art community in Paris. “Some accepted them,” she says. “Others didn’t.” Mondrian did up to a point – but he was far more interested in Moss’s art than her love life.

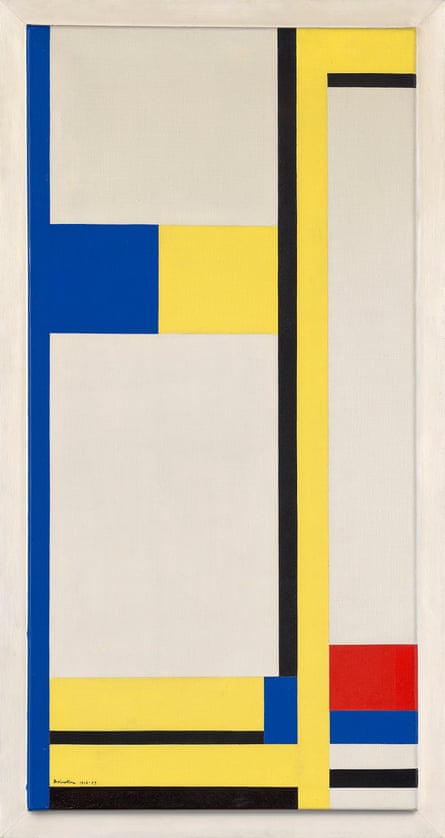

“He was impressed,” adds Dijkstra, “by her experimentation with the ingredients of ‘neoplasticism’ – how she used materials other than paint, such as cork and wood, and her use of the ‘double line’, which allowed for more dynamic compositions.” Mondrian has since gone down in history as the father of neoplasticism, which was all about paring art down to basic components, using only lines and shapes with minimal colours.

When Mondrian saw Moss was deploying the double line in a new way – not using it to cross other lines – his interest was aroused and he wrote to ask what she meant by it. When she told him she regarded the single-line grid he’d been using for over a decade as “a conclusion and restriction” to a composition, he replied saying he couldn’t quite follow what she meant.

Mondrian, however, would go on to become famous for the double line. Clairie Hondtong, the Hague show’s curator, believes its use evolved from exchanges between the two, rather than as something Mondrian created that was then borrowed by Moss, as earlier art historians believed. “For a long time, he was seen as the instigator – but, though it’s unclear who used it first, we now know Mondrian was intrigued by Moss’s use of double lines.”

The sands have certainly shifted over the years. Back in 1972, the assumption was that artists such as Moss had been influenced by Mondrian’s use of it. Then came the discovery that Moss had also used it – and the smart feminist money was on him having stolen it. But now, says Hondtong, there’s a new approach. “Many museums put Moss to the front in the originality debate, but we’re moving away from the ‘Who did it first?’ narrative, focusing instead on the interchange of knowledge.”

Visitors to the exhibition will be able to admire Moss’s use of the technique in her 1932 work White, Black, Red and Grey. They will also be able to compare it to Mondrian’s, in his 1937 Composition of Lines and Colour.

Some LGBTQ+ commentators have suggested that Moss’s use of double lines may have been her response to a world that didn’t make space for a gay woman who dressed in masculine clothes. Since her double lines didn’t cross other lines, she effectively opened up a new space on a canvas – one she may have longed for in the real world. “It might have been an expression of her search for freedom,” says Hondtong. “It could be interpreted as an original response for people outside binary spaces.”

How does Moss fit into today’s transgender debate? “If she was alive today,” says Hondtong, “would she identify as trans? We can’t know – and we don’t want to put words into her mouth. It’s certainly great that she was seen as a pioneer and is an inspiration for queer artists today.”

In 1940, Mondrian moved to New York. Moss, by then living in the Netherlands with Nijhoff, returned to Cornwall, since her Jewish ancestry made life impossible in now-Nazi occupied territory. Mondrian urged her to follow him, but she did not. He died there in 1944, and the two never met again. In Lamorna, Moss seems to have found acceptance and a place conducive to her work. After the war, she reunited with Nijhoff and the pair continued to be lifelong companions until Moss’s death in 1958. They split their life between Cornwall, Paris and the Netherlands, where they lived sometimes on a houseboat in The Hague.

New York, whose grid-like streets echoed Mondrian’s works, helped catapult him to global fame, and he has gone down as a giant of art history, one of the three greatest Dutch painters – along with Van Gogh and Rembrandt – of all time. He is regarded as a central pioneer on the journey from figurative to abstract art, and in the US his work connected with the jazz music and boogie-woogie of the time. In 2022, his Composition No II went for $51m, the record for a Mondrian.

Moss, by contrast, became a footnote in art history, a situation compounded by the destruction of much of her work when a house in Normandy where she and Nijhoff had lived was bombed by the Allies in 1944. It’s the discovery of a suitcase full of sketches that has prompted The Hague exhibition. “The case was left in the Netherlands,” says Hondtong. “It was acquired by the Kunstmuseum in 2025.” A lot of the works were undated, but it’s believed some are from the early 1940s. There are rare examples of her sketches, which reveal much about her thought process.

“We see her using mathematical calculations to plan her geometric paintings,” says Hondtong, “which is very different from Mondrian. She was very precise and her works were carefully mapped out, whereas Mondrian worked more intuitively.” Also in the suitcase are automatic drawings, revealing another layer of Moss’s oeuvre.

Hondtong hopes the contents of the suitcase will spur a new chapter in the artist’s legacy, a focus on her work rather than her life story – an ambition supported by Lucy Howarth, author of the only book in English on Moss, a short eponymous biography. “Moss has a fascinating story. For most people, the way into knowing about her is via the Mondrian link. But she deserves to be explored in her own right. She’s been downplayed by Mondrian scholars for years, but she is one of the few top-tier non-figurative British artists from between the wars, and she was the only Briton and the only female artist who appeared in all five Abstraction-Creation journals.”

Howarth, a historian at the University for the Creative Arts in Canterbury, has been researching Moss since the early years of the 21st century, and says much has changed. “In those days, I’d be looking for her work in storerooms and back rooms. Today, Moss’s work is up on the walls and much sought after for exhibitions.” The upcoming Berlin sculpture exhibition is co-curated by Howarth. “Moss worked in metal, stone and wood and we’ll have about 10 pieces,” she says. “But we’ll also have photographs of sculptures that were lost.”

Unlike Mondrian, who was a painter, Moss was a constructivist who used a range of materials and methods. The new show, it is hoped, will shift the focus on to that. Nijhoff once described her partner as an artist whose work was all about space, movement and light – and that’s every bit as true of her sculpture, says Howarth.

Perhaps most exciting of all is the idea that the current focus on Moss is reframing art history. For centuries, it’s been the story of singular men, geniuses who toiled alone brilliantly to change the direction of the canon. “We’re realising art history is a lot more interesting than that,” says Howarth. “Mondrian was an amazing artist, but he wasn’t the only one practising neoplasticism. It’s so interesting to find lesser-known artists and to examine their impact – and it’s no surprise to find many of them were women and/or queer. Their presence complicates the story. But it also enriches it – for all of us.”

.png) 1 month ago

35

1 month ago

35