Corinne Fowler remembers sitting alongside her son in their garden shed during the first Covid lockdown, when the very start of what would become an avalanche of hate mail popped up in her inbox.

“There was a barrage of emails but the first one just said in the title: ‘You’re cooked.’ And it went on from there,” recalls the historian, who in 2020 had just published a landmark report into the colonial history behind some National Trust properties.

The author of the email, she adds, seemingly shared the views of some prominent Conservative MPs, such as Jacob Rees-Mogg, who had accused Fowler and the trust of “denigrating” British history by detailing the connections to slavery of 93 historic places in the charity’s care.

Looking back now, Fowler believes “heated rhetoric” from politicians and others encouraged anger and even death threats against her and the National Trust’s director general, Hilary McGrady.

An intervention by leading historical bodies took some of the heat out of the debate over the trust’s perceived “wokeness” and headed off threats of interference by the Conservative government.

But the actions of the trust itself – alongside supporters including a slew of keyboard warriors – have also worked to blunt the impact of the culture war the charity found itself caught up in.

Four years on, the National Trust has largely defeated repeated attempts to elect opponents to its council, which appoints board members – though the latest is coming up this week. Some hope that its fightback may serve as a lesson to other bodies caught in culture war crosshairs.

The National Trust – Europe’s biggest conservation charity, with more than 5 million members – is considered by many to be a treasured institution.

Founded 129 years ago and later imbued with statutory powers as the foremost guardian of Britain’s historic properties and countryside, fault lines have always run through the body – from tussles over how to respond to the postwar growth of mass recreation to the aftermath of the 2004 ban on foxhunting.

But in recent years an insurgent group called Restore Trust, as well as media and Conservative figures, began to spearhead a campaign to oppose some of its decisions – especially about efforts to address links to slavery and Britain’s colonial past.

They have included Kemi Badenoch, now a frontrunner to become the next Conservative party leader, who this year accused the National Trust of using “anti-white” rhetoric after the charity replaced the term “ethnic minority” with “global majority”.

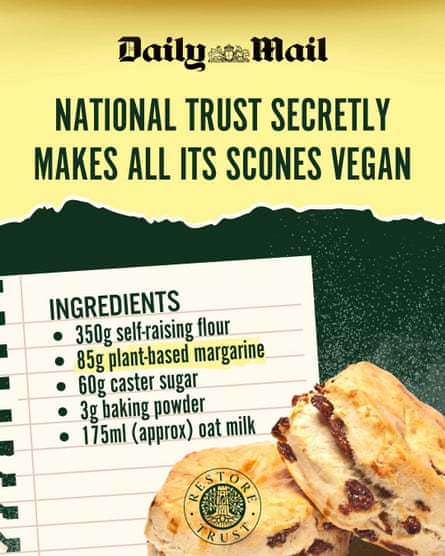

One of the most recent so-called controversies concerned a plan to make 50% of food in National Trust cafes vegan and vegetarian as part of a commitment to reach net zero by 2030.

For McGrady, faced with accusations of “wokeness” and erring from the National’s Trust’s focus on conservation, the key response has been one of going on the offensive.

The National Trust has examined the claims levelled at it and acted robustly to call out what she described as “breathtaking misinformation”, McGrady said.

“In the early days we were on the defensive,” she recalled, speaking to the Guardian on the sidelines of this year’s Labour party conference. But, she said, “there was a moment – without naming names – when there was a news piece about us that was just complete nonsense.

“And we actually just said you’re not telling the truth here and we started to push back in a very systematic way every time there was something untruthful. People have been sitting up and taking notice, because we’ve been really vigilant, so pushing back in a respectful way seems to be a good strategy”.

A key figure was Celia Richardson, the trust’s director of communications, who has used her personal X account to relentlessly rebut claims.

When it comes to disinformation, Richardson speaks of taking “a broken windows approach” – borrowing from the criminology theory that addressing low-level problems creates an atmosphere that discourages larger ones. “Repair every window, otherwise it’s much easier to break more windows,” Richardson said.

In an opinion piece for the Guardian this year, she wrote: “We’ve had to be open and direct about what’s behind untrue stories wherever possible. We’ve answered all media questions, and consistently sought corrections.

“We’ve been careful not to use major platforms for countering disinformation – no one travels to our Instagram to see rebuttals of culture-war stories. We’ve spoken to other institutions and charities about what’s happening.”

Other prominent defenders of the charity have included Matthew Sweet, the broadcaster and cultural historian, who factchecked claims made by the National Trust’s biggest nemesis, Restore Trust, and frequently crossed swords with the organisation online.

“Restore Trust had an X account which kept on making very strange assertions. I remember the first one I checked out was after they used photographs from Hanbury Hall [a stately home in Worcestershire] in 2020 and 2021 and claimed that ornamental lamps, torchères, in the style of black servant figures had been removed,” Sweet recalls.

“Yet not only had they not disappeared, they only arrived in the house after the National Trust had bought it. So the idea that something ancestral was being disturbed was frankly nonsense, as were other examples being pumped out by this frankly very cranky account. None of them stood up.”

A source associated with Restore Trust at the time said its tweet was only pushing back against what it claimed were National Trust moves to remove items from view as part of a programme of “decolonisation”.

Ornamental lamps – and vegan scones – are just some of the fronts seized on by Restore Trust, which presents itself as a grassroots movement of thousands of current and former National Trust members.

It denies being an “astroturf” group – these rely on hidden donors while presenting themselves as grassroots campaigns – but has declined to reveal who funds it.

Restore Trust’s inception dates to April 2021 when it was incorporated as a company called RT2021 at a time when the temperature of Britain’s post-Brexit culture wars was beginning to rise, particularly when it came to history.

Two months earlier, the culture secretary, Oliver Dowden, had summoned the leaders of 25 heritage bodies to a summit on contested heritage. He had been criticised the previous year by the Museums Association, which accused him of threatening to withdraw funding if bodies did not align with the government’s stance on areas including the removal of statues venerating those with links to slavery.

Restore Trust’s directors included the communications specialist Neil Bennett, and a director of RT2021, a company handling what he later told the Guardian was a “significant and growing amount of donations”.

To date, its attempts to exert influence at National Trust annual general meetings have mostly been defeated each year.

Members at a record turnout at the 2021 AGM narrowly rejected motions put forward by the group, although three of its preferred candidates were elected. At the 2022 AGM, candidates backed by Restore Trust failed to win seats while resolutions against National Trust participation in Pride events and rewilding also failed.

Restore Trust’s preferred candidates, including the former supreme court judge Jonathan Sumption, again fell short last year.

A year later, accounts suggest a new threat was headed off when parliamentary supporters of the National Trust leadership rallied to dilute what they feared would be an assault from Westminster.

Having got wind that the Tory backbencher Andrew Murrison intended to set up a new all-party parliamentary group (APPG), other MPs and peers quickly scrambled to turn up at the group’s inaugural meeting. A Labour backbencher, Luke Pollard, was made co-chair along with Murrison while the National Trust later took on an administrative role as its “secretariat”.

“It was quite clear what was going on, that this was going to be a vehicle for parliamentary criticism of the National Trust, but people basically turned up to make sure that didn’t happen,” recalled one person present, and who said they were “100% certain” that the plan had been for Restore Trust to run the group.

Murrison, a critic of the National Trust’s direction in recent years and whose South Wiltshire constituency includes one of its best-known properties, Stourhead, doesn’t recognise this account and said he would have been concerned about Restore Trust taking the role.

He said: “Any great institution, particularly one that’s constituted the way the National Trust is, needs to be open to scrutiny. Parliament is where you do that and so it seemed to me that there was a need to have an APPG to do precisely that.”

More broadly, he echoes a viewpoint shared by Restore Trust and others, which is that the trust has diverged over the past 10 years from its “fundamental role as a clerk of works” looking after the fabric of sites entrusted to it.

“I think most people want the National Trust to be a completely politically free space. They go to its properties for leisure, recuperation and solace, and they expect the National Trust to be a custodian of some of our most important places. They did not expect it to proselytise or advance a particular cultural or political view.”

Last year, Restore Trust began to deploy paid adverts on Facebook/Meta in the name of an offshoot called Respect Britain’s Heritage.

More than £95,000 has been spent on such attack ads to date, according to data from Meta’s Ad Library, and politicians including Rees-Mogg and the Reform UK leader Nigel Farage have shared them before the 2023 AGM.

The defeat of Restore Trust again at last year’s AGM prompted jubilation among members – and a number of people who had been long involved in Restore Trust ceased to be directors.

But National Trust insiders remain vigilant ahead of this year’s AGM, which will be held on Saturday. Opponents of policies concerning not just the charity’s colonial past but also net zero and diversity are renewing efforts to establish a beachhead of influence.

And attacks on the National Trust’s direction are now being fought on other fronts.

Take History Reclaimed, a not-for-profit that claims to be an “independent group of scholars with a wide range of opinions on many subjects”. Its website is a platform for articles attacking supposedly “woke” causes such as the repatriation of historical artefacts.

History Reclaimed’s editorial advisory committee includes Cornelia van der Poll, an Oxford lecturer who was one of Restore Trust’s co-founders, along with historians at the forefront of combating what the right has seen as a relentless attack on Britain’s imperial legacy, such as Niall Ferguson and Nigel Biggar.

The group’s deputy editor is Zewditu Gebreyohanes, who stepped down as Restore Trust’s director late last year. This year, she authored a critical report called National Distrust at the Legatum Institute, where she now works.

The influence of the institute – a pro-Brexit free-market thinktank funded by the Dubai-based Legatum investment group – is a particular concern for those at the National Trust, who defend what they view as duties to respond to the climate crisis and make the charity a welcoming place.

The investment company is also a backer of GB News, which has become a platform for frequent attacks on the National Trust.

Gebreyohanes said: “Far from debunking claims, it is important to remember that the National Trust’s management have at every step sought to deflect attention from the very real issues afflicting the trust about good governance and accountability, which they have consistently undermined.”

She also cited concerns expressed by a former National Trust chair, Sir William Proby, who wrote that governance changes were taking the charity in the wrong direction.

All of the above unfolded before Labour’s landslide election win in July. At the party’s conference last month, McGrady expressed the hope that the new government would mark an end to a “war”, which she said was not of the charity’s making, and encouraged Labour to prevent further “political” appointments to public bodies.

Referring to a fraught encounter under the last government, she said: “I was in a meeting at one point where a minister at the time said: ‘I’ve been appointed and it would appear I’m not allowed to have any influence.’ And actually that was the point. You were not meant to have any influence on it.”

But she was also candid about enduring tensions between the often younger, more liberal makeup of charity workforces and the different demographics of their users.

“I would say 70% of my staff and volunteers would be regarded as progressive activists so I have a workforce of people who are really wanting to push on this,” she said, referring to issues the trust campaigns on and contrasting these with its membership base.

“I wouldn’t want to characterise our members as particularly conservative. They are actually not but there is a dynamic that I as a director general need to be aware of – that my organisation is pushing very hard on one side while I need to be aware of how the public are receiving that.”

Earlier this year, before he became prime minister, Keir Starmer pledged to defend organisations such as the National Trust and Royal National Lifeboat Institution, accusing the Conservatives of attacking them to stoke a “desperate” culture war.

However, a former Conservative minister is among those who caution against the idea that the arrival of Starmer in Downing Street spells respite for the charity – whether or not Badenoch becomes the next Tory party leader at the weekend.

“Labour could be the salvation of the National Trust but it also carries a risk in that the latter will be seen as even more part of an establishment, and that puts them even more at risk from a Tory party that is lashing out,” said the former minister.

“On the one hand, there will be a much more benign environment, but on the other the trust could be elided with a Labour government’s supposed ‘woke agenda’.”

And any hopes that Badenoch, if she does win, will drop the issue seem ill founded. A direct link between the former equalities minister and the campaign against the National Trust has emerged, with Badenoch running her leadership campaign from a property owned by Neil Record, one of Restore Trust’s original directors.

Record, a Tory donor, has previously donated to the Global Warming Policy Foundation, which was set up to question climate crisis policy, and now chairs Net Zero Watch, which seeks to highlight what it calls the “costs of net zero”.

Record, van der Poll and members of Restore Trust were approached for comment.

.png) 2 months ago

20

2 months ago

20