I’m assured this is a big deal: on the far side of a field in Thetford, separated from me by a gate, there is a stone-curlew.

Jon Carter, from the British Trust for Ornithology, patiently directs my binoculars up, down and past patches of grass until my gaze lands on an austere-looking, long-legged brown bird. “Quite a rare bird,” Carter says, pleased. “Very much a bird of the Breckland.”

As a very beginner birder, I’ll have to take his word for that.

My interest was sparked early this summer when a friend introduced me to Merlin Bird ID. Developed at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology in Ithaca, New York, the app records birdsong and uses artificial intelligence to identify particular species – like Shazam for birds. Merlin has added a new dimension to my walks, sharpening my awareness of wildlife I’d ordinarily have tuned out. I can now identify one bird by song alone (the chiffchaff – it helpfully says its name).

Having surged through the pandemic, birding may be taking off once more. Merlin has recently been shouted out on the ultra-cool NTS radio station and on Instagram by Sarah Jessica Parker, while The Residence, the recent Netflix whodunnit from Shonda Rhimes’ production company, features a birdwatching detective.

Birding not only gets you outdoors and moving, but engages you in nature; both benefit mental and physical health. A 2022 study found that everyday encounters with birdlife were associated with lasting improvements in mental wellbeing. Even simply hearing birdsong can be restorative.

But how do you go from noticing birds to becoming a full-blown birder? Carter and other experts took me under their wings.

Start where you are

Carter is leading me through the BTO’s Nunnery Lakes reserve, just south of Thetford in Norfolk. Sixty species of birds breed here between March and August, and more stop over. In just 20 minutes, we spot a dozen or so, including a charming family of great crested grebes.

Many birders practise “patch birding”, focusing their entire practice on just the one area, Carter tells me: “It’s quite addictive.” He discovered birding aged 11, when his family moved close to the RSPB’s Leighton Moss nature reserve in coastal Lancashire. “Suddenly, birds became the absolute focus.”

But even urban areas teem with birdlife. Nadeem Perera, an RSPB ambassador and co-founder of the birding community Flock Together, got hooked after spotting a green woodpecker in a suburban London cemetery. “I couldn’t get over how strikingly beautiful this bird was, and moreover, that it was on my doorstep,” he says.

At the time, Perera was 15 and had just dropped out of school. He was feeling hopeless and disengaged. The woodpecker represented hope and possibility. “All I knew was that being exposed to birds in their natural environments made me feel good – so I kept on going.”

Fifteen years later, Perera can confidently identify most birdsong in London.

Get to know your neighbours

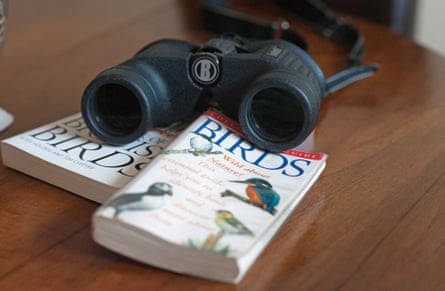

With more than 600 bird species recorded in the UK, Carter suggests starting with those you’re most likely to encounter locally. A field guide such as Collins Bird Guide is the best way to familiarise yourself with different types of birds and helpful vocabulary.

By learning a little about the taxonomies – and what distinguishes, say, a passerine (perching bird) from a petrel (seabird) – “you very quickly learn how to describe the birds you see,” Carter says. But don’t feel pressure to become an expert, he adds. “People can just enjoy being in nature because it’s valid and valuable.”

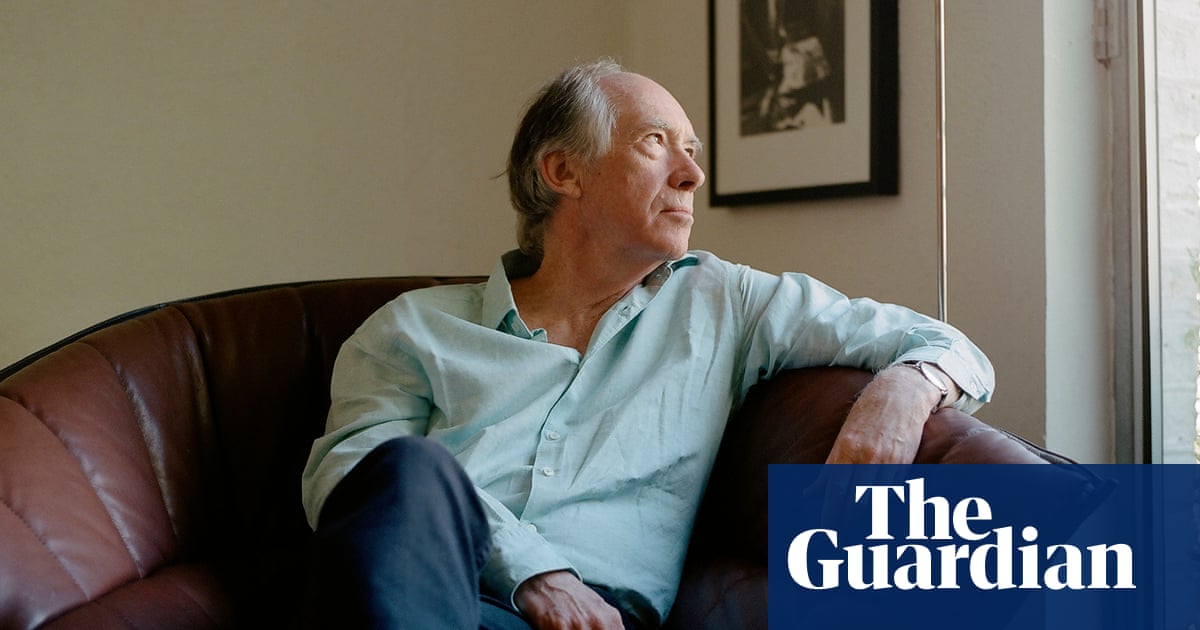

Amy Tan, the bestselling author of The Joy Luck Club, became a “back yard birder” in 2016, following Donald Trump’s election. “It was so depressing – I needed to find beauty again in the world,” she says. At the time, Tan was 64. Birding brought her calm and a refreshed perspective, “getting distracting and distressing elements out of my head so I could continue with my day”. Soon she became “obsessed” with birds; at one point, she even stored live mealworms in her fridge.

In her book The Backyard Bird Chronicles (a US bestseller, to be published in the UK in August), Tan captures her visitors with whimsical descriptions and drawings. She can now identify more than 70 species – but that knowledge came gradually, she says. “If you take on too much at once, it’s overwhelming, and then you just don’t want to do it any more.” Naming birds “does not have to be a criteria” to enjoy them, she adds. “It’s a very democratic hobby, or passion – or obsession.”

Do make use of technology …

Technology can be a gateway to green spaces, as demonstrated by my experience with Merlin Bird ID. It’s useful for engaging young people in particular in the natural world, Carter agrees – and perhaps more realistic than urging them to leave their phones at home.

The Collins Bird Guide is also available as an app for on-the-go referral (though most birders seem to use the app alongside the hard copy, since the book is easier to browse). Carter also recommends the BTO’s free app BirdTrack, which allows users to record their sightings, review those of others, and contribute to research. Some people prefer eBird, which, like Merlin, comes from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology.

… but don’t forget to pay attention, too

Though apps can augment birders’ experience in the field, they can also distract from it. Carter says Merlin is best used in addition to your own instincts and identifications, rather than as a replacement – not least because “it’s not 100% accurate”. And by immediately reaching for the app to ID a bird sighting or song, you also risk skipping over steps that would make that knowledge stick or feel earned.

I have now started using Merlin only after making my best guess as to what species I’m hearing. I am usually wrong (unless it’s a chiffchaff) – but I feel as if I’m training my ear.

Birding requires patience, which is at odds with our on-demand culture, Perera points out. That’s “one of the great things” about it – but it can be a tough adjustment. “This isn’t Netflix. There’s every chance that you will see nothing. Then you realise: ‘Oh, wow, the world actually doesn’t happen on my terms,’” he says. “It humbles your ego a little bit. But it makes you very appreciative of those magical moments when you do see the bird that you’re after.”

Get your ‘bins’ out

Birding is a widely accessible, even generally free pastime – “but if you want to do it to a certain standard, you need to buy a pair of binoculars,” Carter says. As a one-off expense, it’s worth putting in the time to find a pair that suits your purposes (and ideally try before you buy). Magnification is not the only consideration, Carter says; some have a brighter picture, but might be less sharp. Weight and size are also important. “It’s about finding ones that feel right in your hand.”

Premium-brand “bins”, such as Leica and Zeiss, go for more than £1,000. (An AI-assisted pair made by Swarovski – yes, like the crystal – will set you back £3,695.) Budget models have come a long way, but Carter warns against scrimping: “You’re not going to get anything under £150 or £200 that’s even really useful. But once you’ve got it, you’re done.”

Think of it as an investment, echoes Sam Walker of the Wildfowl & Wetlands Trust (WWT) charity. “You don’t have to spend thousands, but it’s really key. Even if it’s just a small pair of field binoculars, they’re going to set you up for decades into the future.” He suggests buying top brands secondhand, available at a fifth or even a tenth of the price of new. Walker’s own binoculars and telescope are probably more than 10 years old, “but it’s still great-quality glass”.

Find your flock

Birding is often a solitary pursuit, but it doesn’t have to be. “It’s a more social hobby than you’d think,” says Walker. He got into birding six years ago when he started working at the WWT, and says the best way to learn is by going out with people with more experience. “It’s much easier to identify birds and retain information, because you’ve got others there to bounce ideas off. I’m always really keen to not be sat in a bird hide, on my own, in the dark.”

Nature reserves and organisations such as the BTO and the RSPB put on birding walks, talks, training courses and events. Joining a local bird club is also a great way to meet like-minded people. Birding may still be dominated by older, white men – but that is changing. The BTO and RSPB both have youth wings, while groups such as Birds & the Belles and Birding for All are working to make the pastime more inclusive.

Perera and Ollie Olanipekun co-founded Flock Together in 2020, as a “birdwatching club for Black and brown people”. Five years on, it holds monthly birdwatching walks and has chapters in Tokyo, Toronto and New York. “Don’t let anybody intimidate you, or make you feel as though you don’t belong,” says Perera, who is of Sri Lankan and Jamaican heritage. “They’re just scared that you’re going to be better at it than them.”

Start a list, or a system

Birders love to log their sightings: the most common records are “year lists”, covering the calendar year, and “life lists” that include everything. Walker’s 2025 list is currently at 130 species, sighted around his Gloucestershire home – but he knows birders with life lists tallying 600-plus. “You can imagine the amount of time and money that they’ve spent travelling around.”

Many birdwatchers will go to great lengths to secure rare spots. “It just adds a little bit of magic sparkle to your birding year, and builds up that life list as well.” But even patch-birders, focused on their local area, can get a bit obsessive about trying to catch ’em all, Walker admits. “People get worried about going away on holiday.”

While some structure or system can support your developing hobby, Carter discourages being too focused on outcomes. “I’ve seen quite a few young people get into the rarity, list-building thing.”

Earlier this month, a Pallas’s reed bunting was spotted on Fair Isle in the Shetlands – only the fifth sighting recorded since 1976. Though the bird itself is small and unshowy, excitement levels were high: “A mostly monochrome masterpiece, this was the stuff of birding legend,” wrote the Rare Bird Alert newsletter. Carter recalls: “straight away, people were trying to figure out if they could get charter flights, whether there were any boats running …” He advises slowing down. “Take your time; learn to really love birds.”

It’s enough just to look

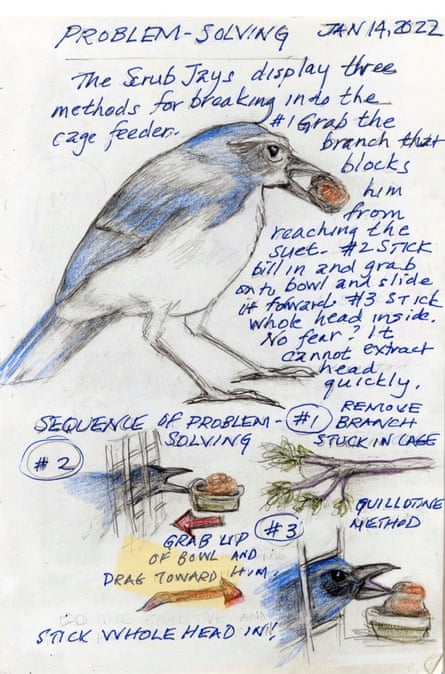

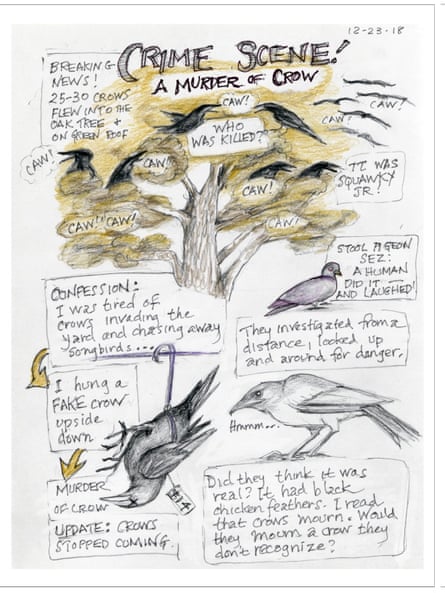

Tan decries some birdwatchers’ elitism, and dismissal of common species. “They’ll call a starling or sparrow a ‘junk bird’; I think that’s horrible.” She approaches birding as a practice of observation, and even mindfulness. “You can start noticing what a bird is doing – these ordinary behaviours that we don’t always pay attention to.”

Tan also studies the pecking order playing out at her feeders. “Trying to decipher the relationships – that’s part of the fun,” she says. Drawing each bird pushes her to focus on easily missed details such as bill shape or foot colour, and “the way that each individual bird is actually constructed”.

Keeping a journal or a diary (as The Backyard Bird Chronicles began) helps “anchor” her practice, Tan says. “It’s a good brain exercise, if you’re a writer, but also just for remembering the things that made your life so meaningful and joyful.”

Broaden your horizons

Once you’re familiar with your patch and its regulars, you can start attuning yourself to seasonal variations. Many migratory birds arrive in the UK during the spring, staying for the summer and leaving just as winter visitors are descending.

The time of day and the weather affect sightings, too. Birdlife is typically most active at dawn and dusk. While rain can worsen visibility and make some species less active, it enlivens others and causes them to fly closer to the ground, making them easier to spot.

Strong onshore winds can blow seabirds towards the coast from open water, and cause migratory species from North America, Europe or Asia to make a pit stop on British shores. Just a short drive or train ride can transport you to a different habitat hosting unfamiliar species, Walker says. “Even in London, you can get out to heathland or down to the coast.”

The eBird and BirdTrack apps, alerting on recent sightings and particular hotspots, can give you a sense of what to look for – but in general, Walker says, “being out and always birding is the best place to be”.

Be part of something bigger

As well as offering an escape from screens, work and day-to-day stresses, birding can deepen your investment in nature. You might notice the changing climate in your area, or get involved in local efforts to protect green spaces. “It connects you to it, so you care about it, and you’re concerned when someone wants to fill in your local pond or build a road through woodland,” says Carter.

You can contribute to science and conservation efforts by logging sightings on BirdTrack, adding to a national database of “what’s where and when”. The BTO also conducts regular projects and surveys – of wetland birds, breeding birds or garden birds – involving thousands of volunteers each year. Even beginners can play a part, says Carter.

“Every record is of some value: if you identify only half the birds you saw, that half is still really useful. You don’t have to be an expert in telling one weird wader apart from another weird wader – there are always people who are good at that.”

.png) 2 months ago

25

2 months ago

25