Back in early 2016, as Donald Trump ran for president, he issued a warning that sent a chill down the spines of journalists and press advocates.

After ranting about the New York Times and the Washington Post at a Texas campaign rally, Trump predicted that traditional news organizations would have big problems if he were elected. He planned to “open up” the libel laws, so that “when they write purposely negative and horrible and false articles, we can sue them and win lots of money”.

As with many of Trump’s threats, that one didn’t come to fruition. More than eight years later, the law still stands that public figures can only win a lawsuit against a news outlet if it can be proved that the outlet published information knowing it was entirely false or had a “reckless disregard” for the truth. The 1964 supreme court case, New York Times Co v Sullivan, which established this press-protecting precedent, hasn’t been overturned.

But a lot has changed since 2016 – including the increasingly conservative bent of the US supreme court after three Trump appointees. If Trump is elected in November, the laws that protect news organizations might crumble or be weakened.

And while Trump did not get his wish about changing the libel laws, he nevertheless has done a great deal to damage press rights in America.

As president for four years – and as a candidate both before and after that term – Trump has continually waged war with the mainstream press while he used the rightwing press for his political purposes.

As recently as this month, Trump demanded that CBS News be stripped of its broadcast licence as punishment for airing an edited answer of an interview with his Democratic rival, Kamala Harris and he threatened that other broadcasters ought to suffer the same fate.

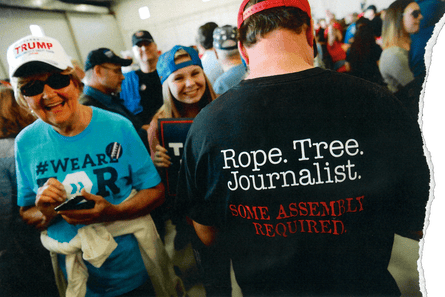

For years, he stirred up hatred of reporters by calling them the “enemy of the people” – an echo of the language of fascist dictators. He frequently referred to legitimate journalism as “fake news”, and publicly insulted individual reporters.

Famously, in 2018, the Trump White House revoked a CNN reporter’s press pass as retaliation for persistent questions at a press conference. Trump called that reporter, Jim Acosta, a “terrible person”.

“This is something I’ve never seen since I started covering the White House in 1996,” wrote the New York Times correspondent Peter Baker. “Other presidents did not fear tough questioning.”

Trump made a point of disparaging reporters, particularly women of color, and of questioning their intelligence or integrity.

Over the course of one week in late 2018, he berated three Black women reporters – Yamiche Alcindor of PBS, April Ryan of American Urban Radio Networks and Abby Phillip of CNN.

“You talk about someone who’s a loser,” he said of Ryan. “She doesn’t know what the hell she’s doing.”

Trump’s enmity took many forms, including lawsuits. In 2022, he sued the Pulitzer prize board after they defended their awards to the New York Times and the Washington Post. Both newspapers had won Pulitzer prizes for investigating Trump’s ties to Russia.

Read more from the series

More recently, Trump sued ABC News and George Stephanopoulos for defamation over the way the anchor characterized the verdict in E Jean Carroll’s sexual misconduct case against him. Each of those cases is wending its way through the courts.

There is nothing to suggest that Trump would soften his approach in a second term. If anything, we can expect even more aggression.

Consider what one of Trump’s most loyal lieutenants, Kash Patel, has said.

“We’re going to come after the people in the media who lied about American citizens, who helped Joe Biden rig presidential elections,” Patel threatened during a podcast with Steve Bannon. “Whether it’s criminally or civilly, we’ll figure that out.”

Patel, a former federal prosecutor who was Trump’s counterterrorism adviser on the national security council, has been mentioned as Trump’s pick for FBI director or attorney general.

It’s this kind of rhetoric, combined with Trump’s past behavior, that caused one Washington-based science writer to express his concerns in a piece titled “Will Journalism Be a Crime in a Second Trump Administration?”

Environmental journalists “are used to worrying about things that are endangered”, wrote Joseph A Davis in the journal of the Society of Environmental Journalists.

“So we think it’s time to add press freedom and democracy to the endangered list.”

In addition, consider Project 2025. The blueprint for a second term from Trump’s allies is a press-rights nightmare.

Under Project 2025, seizing journalists’ emails and phone records would get easier. The editorial independence of Voice of America would be sharply curtailed; in fact, the global organization might be shut down altogether. Former officials who talk to reporters would be punished. Funding for NPR, PBS and public broadcasting would dry up.

“A pretty grim picture,” was the conclusion of Joshua Benton of Harvard University after analyzing Project 2025 from the perspective of press rights.

“The first time around, there was at least a modicum of uncertainty about what a Trump administration would actually do,” Benton wrote in Nieman Lab. “The second time, voters knew better, and they rejected it. The third time? Well, no one can say it’ll come as a surprise.”

As for Kamala Harris’s attitude toward press rights, we don’t know a great deal, except that she’s doing things in the normal, pre-Trump way.

Her web site’s policy section trumpets her defense of “fundamental freedoms”, stressing reproductive rights and voting rights, but not freedom of the press.

In a new report on press freedom and the election, the Committee to Protect Journalists reports that neither presidential candidate responded to their request to pledge clear support for press freedom.

The CPJ report found that Trump’s antipathy for journalists has left lasting harm, from the local to the global level, harm that was not adequately repaired during the Biden years.

“The hostile media climate fostered during Donald Trump’s presidency has continued to fester, with members of the press confronting challenges – including violence, lawsuits, online harassment, and police attacks – that could shape the global media environment for decades,” according to the report.

“The stakes of this election are incredibly high,” the report’s author, Katherine Jacobsen, told me.

After Joe Biden passed Harris the torch over the summer, the vice-president came under fire for not quickly sitting down for an interview or doing a press conference.

She promised to do an in-depth interview by the end of August – and met her self-imposed deadline.

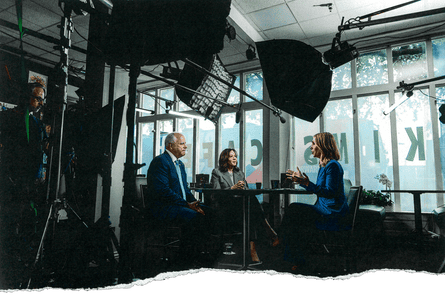

That first was with CNN’s Dana Bash, certainly a mainstream choice. Harris has since fielded questions from members of the National Association of Black Journalists at WHYY, the public radio station in Philadelphia. And she sat down in September to discuss her economic policy plans with MSNBC’s Stephanie Ruhle.

There’s little to suggest that she’ll try to portray the press as the enemy of the people or start prosecuting journalists under the Espionage Act. Such prosecution did happen under Trump. (It also did under Barack Obama, though that has been largely forgotten in the chaos of the last eight years.)

Trump’s justice department seized the phone and email records of a New York Times reporter, Ali Watkins, and used the Espionage Act to jail a journalistic source, Reality Winner, for leaking a classified document about Russian interference in the 2016 election.

Trump’s affinity for autocratic leaders adds another layer of concern.

Writing in the Washington Post, the publisher of the New York Times, AG Sulzberger, raised an alarm about whom Trump looks up to.

“If Trump follows through on promises to continue [his anti-press] campaign in a second term,” Sulzberger wrote, “his efforts would likely be informed by his open admiration for the ruthlessly effective playbook of authoritarians,” such as the Hungarian leader, Viktor Orbán.

Sulzberger, though, also wrote that he had no intention of allowing these concerns to affect his paper’s straight-news coverage: “I disagree with those who have suggested that the risk Trump poses to the free press is so high that news organizations such as mine should cast aside neutrality and directly oppose his reelection.” In its opinion pages, however, the Times’s editorial board has called Trump unfit to lead and strongly endorsed Harris, calling her “the only patriotic choice for president”.

It would be heartening to hear Kamala Harris publicly express her support for the essential role of the press in a free society, something to be protected and even celebrated. That may never come to pass.

Still, it’s probably reasonable to assume Harris will treat the press as many Oval Office dwellers have in the past, as something of a burr under the presidential saddle.

By contrast, Donald Trump poses a clear threat to journalists, to news organizations and to press freedom in the US and around the world.

Trust in the media may be low, and American citizens may not be fans of journalists or their work.

But they ought to know that just as longstanding reproductive rights have collapsed in recent years, press rights – already reeling – could suffer the same fate.

-

Margaret Sullivan is a Guardian US columnist writing on media, politics and culture

.png) 2 months ago

23

2 months ago

23