You only have to glance at William Kentridge’s family tree to realise why he is such an outsider. His maternal grandmother, Irene Geffen, was South Africa’s first female barrister while his mother, Felicia Geffen, became an anti-apartheid lawyer. Then there’s his father, Sydney Kentridge, the indomitable QC who represented Nelson Mandela in the 1960s and fought for justice for Steve Biko in the 70s. Studying law would have been the obvious path. “Public speaking, thinking on my feet, were natural and easy skills,” said Kentridge back in 1998. “Being an artist was a very unnatural and hard thing for me to do.”

That’s quite a statement. Because in the three decades since, Kentridge has conquered the international art world with the oomph and verve of an emerging twentysomething. He has exhibited in most major museums and biennales, and his work now fetches millions. Along the way, he has collected 10 honorary doctorates, numerous grand prizes in art and theatre, and a spot on the Time 100 list of influential people. Now, fresh from celebrating his 70th birthday in April, he has two solo exhibitions under way, two group shows, four touring operas, a touring feature-length film and a nine-part film series, Self-Portrait As a Coffee-Pot, streaming globally on Mubi “with an accompanying 836-page book”. It’s almost as if he was, indeed, a natural.

We meet in London, before an expansive show titled The Pull of Gravity, is about to open at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. He suggests we meet at his flat opposite the British Museum and, despite him having to take a flight to South Korea in a few hours, he greets me at the door with gentle aplomb. I sit at the kitchen table while he makes tea and talks about coffee pots. If you set out to do a self-portrait, he explains, you can either attempt some kind of likeness, or you can list, say, all the books you’ve ever read, or all the objects you own, or even just one. “In that sense,” he says, “a coffee pot is as good a way of drawing oneself as drawing a picture of your face.”

And this, it turns out, is something he actually does. “Ironically,” he says, “the coffee pot I draw is the one kind of coffee pot that I don’t like. So they’re not kept in the kitchen. People see them in the studio, though, and they give me more of them. So we have a huge range of these Bialetti coffee pots sitting in the studio and they’re used as paint-holders, brush-holders and flower pots. I suppose, because it’s an absurdity, the self becomes an absurdity.”

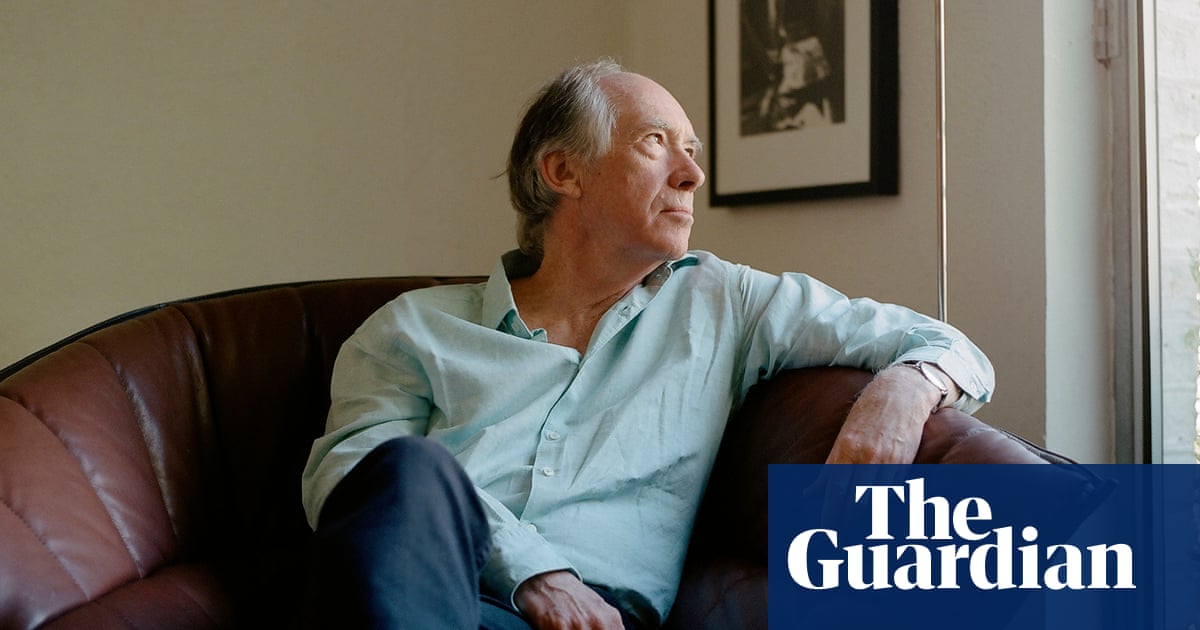

In person, Kentridge is exactly as he is in his films: same cadence, same donnish delivery, same subtle wit, same kindness. Only the blue of the shirt he’s wearing today feels out of place, given how it jars with the crisp white button-down he wears for the films in the Coffee Pot series, in which he appears as several versions of himself (Kentridge One, Two and sometimes Three). In each, these Kentridges sport lopsided pince-nez glasses as they go about the business of the studio. We watch their white shirts getting spotted and smudged, almost as if they’re being slowly subsumed into whatever is being drawn: tree, landscape, stage, mine.

Kentridge still lives and works in the whitewashed turn-of-the-century home he grew up in in Johannesburg. But since 2014, he has also owned this small London pied-a-terre, which looks and feels like a studio, buzzing with paintings, drawings and sculptures. Having it is, in part, to meet the travel demands of an unrelenting international schedule. It also allows him to see family members who live here: his siblings, a daughter and two grandchildren, and his father, who is now 102.

“I was with him yesterday,” he says. “His memory’s going, so he says, ‘What are you doing?’ I said, ‘I’ve been in France.’ ‘What were you doing in France?’ I said, ‘Oh, I was inducted as an academician at the Académie des Beaux-Arts.’ And he said, ‘Ah, my boy, I’m proud of you. It was worth every franc I paid them.’” He laughs quietly. “I’m his 70-year-old boy,” he says.

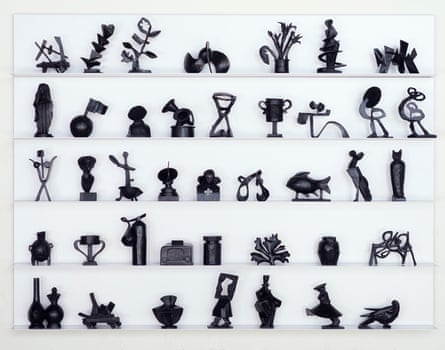

The Yorkshire Sculpture Park show will be the most complete survey of Kentridge’s sculptural work outside South Africa. As a new commission for the park itself, he has created Paper Procession, six monumental cutouts that started out as paper but are now painted aluminium and steel. The largest is more than five metres tall. Further works include four of Kentridge’s largest bronzes and, inside, several sets of tiny bronzes he refers to as “glyphs”: ink flourishes rendered in metal that stand in for things spoken or heard. “The sculpture very often starts as drawing,” he says. “It’s about the weight of a word, the weight of a thought, a way of fixing something that would otherwise be very changeable.”

Belgian set designer and long-term collaborator Sabine Theunissen has designed the exhibition to also include several film works. Oh to Believe in Another World, recently on show at London’s Southbank Centre, examines composer Dmitri Shostakovich’s relationship with Stalin – and the fizz and trauma of the Soviet century. Visually and textually, it is a magnificent DIY medley of dancing, archival footage, puppetry and cut-up dialogue steeped in avant garde experimentation. “There are things from the constructivists that we’re still catching up with,” says Kentridge. “Dziga Vertov’s Man With a Movie Camera – no one has made a film like it in the 96 years since it was made.”

Self-Portrait As a Coffee-Pot, meanwhile, will be on view in its entirety, a mesmerising discussion of art-making and mortality. Each episode takes as its source the genesis of a recent project, with added family stories, memories and some critique. “There was no overarching script,” says Kentridge. “I’m not a narrative writer. I keep thinking I should do a detective story, but I have different skills, a different brain.” Instead, he improvised: “I was recognising things as they emerged.”

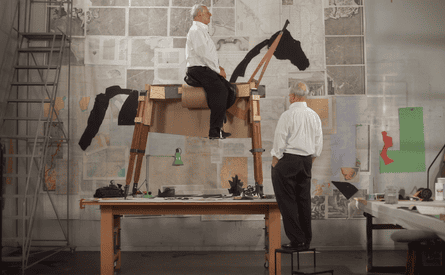

It was filmed in his Johannesburg studio (a “vital, vital place”). You see one or other Kentridge character surveying a sculpture under way, with a baby on his hip or a taller child in tow. The wider family of studio collaborators, assistants and performers make appearances too, as do horses made of cardboard and timber, animated armies of drawing pins, and tiny mice made quickly from putty eraser detritus.

“There are some artists for whom it is very important not to talk about what they’re doing while they’re doing it,” he says. “But I’m someone who works easily and well with people seeing work in different stages. While they’re watching the film, I’m watching them – to see things that are connecting and those that are not.”

Also, he says, talking about the work is not just about sharing – it’s about making. “Somebody says, ‘What film are you making?’ And I don’t really know. But by the end of the conversation, I have a very clear second conversation going on in my head – as I’m calling it into being.”

Theunissen first met Kentridge in 2002, when he was directing and doing animations for Mozart’s The Magic Flute at the Théatre Royal de la Monnaie in Brussels. He was put in touch with Theunissen and he asked if she knew his work. She replied no. “To my shame!” she says. However, he was delighted. Even more so when she admitted she didn’t know the opera well either. She returned the next day with, as a design proposal, a maquette so small she’d transported it in a matchbox. He was sold. “He didn’t even look inside,” Theunissen says. “I think it’s because I immediately started making something. And we still work in the same way.”

This principle of, as Kentridge puts it, “being open to discovery rather than knowing in advance what you’ll do” saw him start an arts centre in Johannesburg in 2015: The Centre for the Less Good Idea. More than 2,000 artists have gone to work at this hub of experimentation, described as unlike anything else in the country. Pianist and composer Kyle Shepherd has contributed to multiple Kentridge projects since meeting him there. “Usually when musicians and artists reach his age,” says Shepherd, “they sort of paint the rhinoceros another 2,000 times, or they play the piece another 1,000 times, because that’s what worked for the last 40 years.” But not Kentridge, says the musician, who thinks of him as “a jazz man”, a master improviser.

“There’s a branch of Hasidism,” says Kentridge, “that believes the words of the prayer are for God and the gaps between the words – the white spaces – are for you. That’s me. In the moment of listening, I absolutely get lost.” In the Coffee Pot series, he describes the studio as a space where impulse is allowed to expand and find its place: “A sound becomes a line. A line becomes a drawing. A drawing becomes a shadow. A shadow gains the heft of a paperweight.” At 70, Kentridge is not slowing down, eyes firmly fixed on what he cannot yet see.

.png) 2 months ago

22

2 months ago

22