At the turn of the decade, gay male and non-binary pop stars seemed poised to take pop music by storm. Lil Nas X broke out with Old Town Road – which blew up on TikTok, sold about 18.5m copies and remains tied with Shaboozey’s A Bar Song (Tipsy) and Mariah Carey’s All I Want for Christmas Is You as the longest-running No 1 single in US history – and artists such as Sam Smith, Troye Sivan and Olly Alexander from Years & Years were all singing about gay love and sex.

But the initial promise has stalled. Lil Nas X’s attempts to build on his smash debut album have fizzled, and he is publicly dealing with mental health issues. In October, Khalid released his first album since being outed by his ex last year but only sold 10,000 copies in the first week in the US. A previous album, 2019’s Free Spirit, sold some 200,000 copies in the first week and led to him briefly dethroning Ariana Grande as the most listened to artist on Spotify.

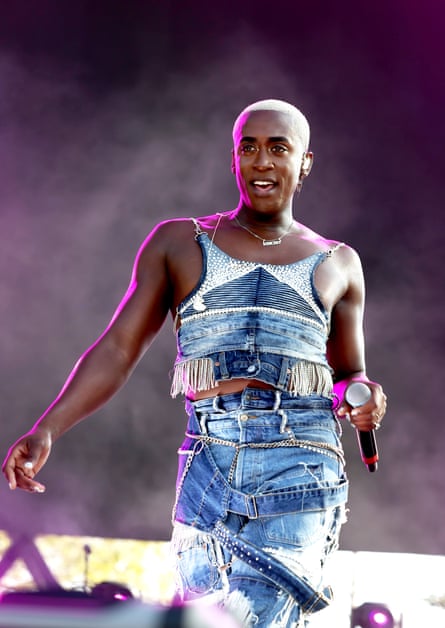

After chart-topping fame with Years & Years, Alexander’s debut solo album, this year’s Polari, could only peak at No 17 in the UK, with no charting singles apart from Dizzy, the UK’s 2024 Eurovision entry, which reached No 42. He tells me that being out in the “major label machine … felt like I was trying to pull off an impossible magic trick”. When it comes to selling gay music to the public, he says, “men explicitly loving men is so threatening to the status quo and patriarchy, which makes it harder to gain mainstream support”. Only Sivan has stayed culturally relevant, if not commercially dominant, thanks in part to savvy collaborations with two of pop’s biggest female stars, Charli xcx and Ariana Grande. How did gay male artists lose their place in the pop landscape?

One surprising reason might be that “there aren’t many male pop stars full stop”, explains Michael Cragg, a music critic and author of the Y2K pop oral history Reach for the Stars. At least, he says, not in the Madonna tradition of bombastic spectacle. “A lot of male artists got swept up in the beige world of Ed Sheeran and Lewis Capaldi,” says Cragg, where today “you can sell millions of albums” with a ballad-heavy repertoire. Cragg cites Calum Scott, best known for his stripped-down cover of Robyn’s Dancing on My Own, as an example of an out gay singer who has succeeded by falling into this “beige world”. Yet Scott’s last tour took him to venues such as the 2,300-capacity London Palladium, while Capaldi is headlining the 65,000-capacity BST Hyde Park next summer.

For gay men in pop, says Jason King, dean of the University of Southern California’s Thornton School of Music, “there’s no question there is a glass ceiling. It’s not like we’ve always had hundreds of queer men in pop music hitting the top of the charts, and suddenly now we’re facing a drought”.

You might argue: what about the 1980s? From here, the decade looks like a golden age of gay pop, thanks mostly to British men: Freddie Mercury (who was British Parsi), Elton John, George Michael, Pet Shop Boys, Dead or Alive’s Pete Burns. But at the time, few were out: pretty much just Bronski Beat and Frankie Goes to Hollywood. Although the straight public’s illiteracy about gay culture was proved when BBC Radio 1’s Mike Read yanked Frankie’s 1984 single Relax off air as he realised what it was actually about. To most people in the mid-80s, what are now unmistakable as queer codes – makeup, androgynous styling, elaborate hairstyles – just signalled “flamboyant pop stars”, which also created an indelible blueprint of how a pop star of any persuasion could look and sound.

Nonetheless, the Aids epidemic brought much of this progress to a screeching halt. Pet Shop Boys’ US career is thought to have stalled because their video for 1988’s Domino Dancing was seen as too gay. Mercury died in 1991. Elton John came out in 1992 when he was well past his pop peak, and George Michael wasn’t outed until 1998. Very rarely have gay pop stars been allowed to be honest about their sexuality in ways that are also commercially successful, as with Bronski Beat’s 1984 single Smalltown Boy or the Scissor Sisters in the early 00s. Lasting success is even more elusive.

Hence why Lil Nas X’s breakthrough felt like a watershed moment, picking up the mantle of the gay men in pop who came before him. Here was an out Black gay man breaking chart records, winning awards and shaping pop culture, thanks to wittily provocative music videos such as Industry Baby, where naked men danced in prison showers. It looked as though true change had arrived. But within the industry, “record labels weren’t running to sign hundreds of gay men in pop, hip-hop and R&B”, says King. Or as Vincint, a gay non-binary singer, says: “Once the industry found one, that was enough.”

In contrast, queer female pop stars have achieved full-beam mainstreaming, among them Chappell Roan, Billie Eilish and Janelle Monáe. Roan’s now familiar presence in the charts makes it easy to forget how extraordinary her meteoric success has been with sexually explicit songs about being a lesbian. Her mass appeal is not just due to the quality of her music, says Cragg, but also gendered dynamics of social stigma and homophobia: “If you’re a straight guy, you can blast Pink Pony Club because you’ve seen all the memes of tough, burly men loving the song. But if your most-played artist on Spotify is Troye Sivan or Sam Smith, you might worry your friends will think you’re gay or less of a man.”

For queer women in pop, says King: “There’s a way in which their sexuality can easily be recuperated by the straight male gaze, so men don’t feel excluded by their queerness.” That same “logic” doesn’t apply to male queerness. Even if a male act finds a supportive label, manager, publicist and booking agent, being pigeonholed as a “gay pop star” can still limit his reach – especially if he’s singing about gay sex.

“I was working with this well-known songwriter and was so close to this dream of a huge deal,” says Vincint. “Two days before, the writer said: ‘I don’t see a place for you. I don’t know how I can make this work.’” Now an independent artist, Vincint has about 102,000 monthly Spotify listeners: a pretty decent number, but one that pales next to an average major label star with a big marketing budget.

Such are the opportunity costs and material consequences that come with being an out male pop star. This pushes some artists into behind-the-scenes roles as writers and producers, such as MNEK, who says: “Major labels aren’t searching for an openly gay pop star. They are searching for something that sells and is palatable for families and middle England.” He now “mostly works with women”, producing the kind of pop hits that gay male acts would struggle to sell.

That’s the other obstacle that gay male singers face: appealing to pop’s biggest audience, straight women, who may not as easily relate to queer men as they do queer women. This is partly why Sam Smith (who later came out as non-binary) chose not to use gendered pronouns on their first album, “so that it could be about anything and everybody”, they said.

Gay male artists also can’t rely on their own community to get behind them. While gay men come out in droves to support their favourite diva, they often reserve their harshest criticisms for queer male (and non-binary) singers, particularly anyone who doesn’t conform to punitive aesthetic ideals. Troye Sivan, Sam Smith, Khalid and MNEK have all experienced backlash: the criticism often boils down to the fact that they are either “too Black, too feminine, or too big”, says Vincint. By contrast, apparently straight acts such as Harry Styles and Benson Boone can push the boundaries of masculinity with queer-coded styling yet remain hugely popular.

All of which puts gay male singers seeking pop superstardom in a difficult place – a situation likely to worsen as equality for LGBTQ+ people faces increasing threats worldwide. Recent polling found that only 54% of US citizens support same-sex marriage (down from 70% in 2021). Pride marches have downsized or disappeared entirely in the US and the UK, and companies such as Disney have cut transgender storylines and been accused of censoring gay characters.

“The tipping point of gayness, queerness and transness has happened and now we’re on the decline,” says a music publicist who wishes to remain anonymous. “I sit in meetings where execs are so dismissive and disrespectful towards queer artists. The music industry doesn’t want to invest in gay male pop stars because they can’t see them achieving mainstream commercial success.”

Gay male musicians clearly haven’t disappeared altogether: many queer men (and those who shun labels) have, says King, “created alternative worlds that allow them to express themselves without having to strive for No 1 hits”. Frank Ocean came out as he released his culture-shifting album Channel Orange, and his refusal to embrace the limelight has made him one of pop’s most enigmatic figures. His Odd Future bandmate Tyler, the Creator used 213 anti-gay slurs on 2011’s Goblin, but later rapped about his relationships with men on 2017’s Flower Boy. The Texan singer-songwriter Conan Gray built his career using TikTok and YouTube, winning over a younger generation who are increasingly eschewing traditional labels of gender and sexuality. He now plays arena shows across North America. They may not have No 1 hits, but each of them is reshaping the boundaries of success in pop music for queer men.

The great irony, however, is that gay men shaped so much of the history of mainstream pop music, one from which many of them are now excluded. Gay cultures such as drag and ballroom have seldom been so popular – albeit sanitised and co-opted by a mainstream more interested in catchphrases than the lived experiences that created them. This exclusion doesn’t just affect musicians, but also queer fans searching to hear their own lives reflected in music, and straight listeners whose worldviews might be expanded by hearing a counterpoint to the rise of rightwing “family values” fanaticism. The success of Old Town Road quashed perceptions that it was just a TikTok novelty hit. Seven years since its release, it represents a much more dispiriting kind of novelty.

.png) 2 months ago

64

2 months ago

64