The arbitrary detention of hundreds of gen Z protesters in Morocco and alleged “horrific” beatings have been condemned by human rights groups, as the country prepares to host the Africa Cup of Nations on Sunday.

A wave of youth-led demonstrations swept across Morocco in late September and early October – the biggest since the 2011 Arab spring – in protest at underfunded healthcare and education.

The government responded to the protests, known as “Gen Z 212”, after the country’s dialling code, by arbitrarily arresting thousands of people, human rights groups said. The Guardian was told that people had been beaten and left for hours without food or water while in police custody.

“My son was at a snack bar having dinner when he was arrested. He was not even protesting,” said a mother whose 18-year-old son had been detained for more than two months.

She said her son had been hit so badly during the arrest that “he even lost some of his teeth”. She said he was beaten again in police custody “simply because he refused to sign police papers of his hearings”.

Female protesters were victims of “acts of harassment, insults, and crude and sexist remarks”, said Souad Brahma, president of the Moroccan Association of Human Rights (AMDH). Some also reported incidents of “inappropriate touching”.

Three protesters were shot and killed, allegedly by security forces, at a protest on 1 October in the town of Lqliâa, near the popular Atlantic tourist hotspot of Agadir. A further 14 protesters were injured, including children as young as 12 left with firearm wounds. The authorities claim a group of protesters stormed the local police station, to which officers responded.

So far, more than 2,400 people are being prosecuted in connection with the protests, and dozens who took part in a non-violent demonstration have been charged with acts of violence, according to Amnesty International.

Dozens had already received prison sentences, some of up to 15 years, said AMDH, which denounced the absence of lawyers during hearings, insufficient investigations and the lack of presumption of innocence. It said hundreds more, including children, remained in detention.

A Human Rights Watch spokesperson, Ahmed Benchemsi, said: “The government clearly got scared and orchestrated this crackdown to send a strong message that they will not tolerate any form of dissent.”

In the aftermath of the unrest, the government said it was committed to social reforms and announced increased spending on healthcare and education.

As Morocco prepared to host the African Cup of Nations, there were renewed reports of unrest in several Moroccan cities, with protesters demanding the release of detained gen Z demonstrators.

There was also criticism after flash floods killed 37 people this week in the Atlantic coastal province of Safi, with protesters saying the government was prioritising international prestige projects over essential infrastructure and services.

But Moroccan human rights groups said many young people remained fearful of returning to the streets again because of the alleged beatings and forced confessions after the September and October protests.

“We have heard horrific testimonies of torture while in police custody,” said Mustapha Elfaz, from the Marrakech branch of the AMDH.

“Some detainees were forced to strip. One mother said her son and his friend were beaten so badly with electrical wires on their legs the marks were still visible weeks later. Her son remains in prison.”

Elfaz said many protesters and families would not reveal what had happened to them for fear of repercussions. “What happens inside prisons now remains largely hidden,” he said.

A lawyer in Casablanca, who has joined a group of about 50 volunteers across the country defending protesters, told the Guardian that there were “multiple procedural violations regarding arrests and police custody”, with severe sentences handed down on insufficient evidence and rushed reports.

The Moroccan authorities said all conditions required for a fair trial were respected from the moment of arrest, with police reports drawn up lawfully and verdicts rendered within reasonable timeframes.

Last week, six relatives of two victims killed at the protest in Lqliâa said they were detained by the police after standing outside parliament in the capital, Rabat, holding pictures of their loved ones. The families said the police took their phones and “deleted everything related to the gathering” before later ordering them to leave the city.

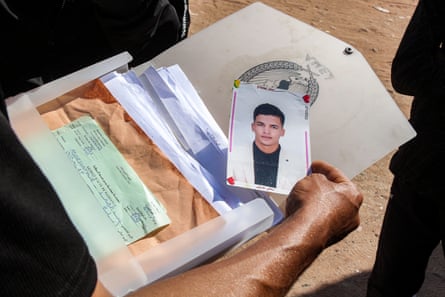

“We just want justice, a transparent investigation and accountability for those responsible,” said a relative of one of those killed, Abdessamade Oubalat, a 24-year-old film-maker.

The Moroccan authorities said the families were taken to a police station after refusing to comply with orders to disperse. It said they had not been arrested or taken into custody.

.png) 2 months ago

66

2 months ago

66