Dog roses blush, honeysuckle trails and elderflower powders the air in East and West Coker. Dressed in May abundance, the sandy Somerset villages radiate genteel nothing-doing respectability. Yet culture, of an invigorating and experimental kind, has penetrated these sun-slowed lanes. Where TS Eliot once meditated on ageing, death and modernisation, the south-west has its very own bite-sized biennale, the Od art festival.

Od isn’t really odd, at least by West Country standards (it’s the name of a crooked stream that runs through the villages). The theme of this fourth edition is Thinking in Circles, evoking seasons, migration and life cycles. There is a link, too, to the starts and failures, death and dung of Eliot’s 1940 poem East Coker (encircling lines from which are inscribed on village signage.) Cumulatively, the 24 artists in the festival raise timely questions about the intersection of the rural and the industrial, the invention of traditions, and the global networks of people and goods through which England is sustained.

Star turn is Libby Bove’s Museum of Roadside Magic. Occupying a customised truck, it has toured the south-west off and on since Bove’s graduation from Bath Spa last summer. The peripatetic archive contains the invented ephemera of songs, dances and esoteric practices used in “vehicular maintenance, repair and journey making”. Artefacts include maypole-type figures whose coloured ribbons represent “the wiring arrangements of a seven-pin plug”, a photograph of the font of “St Dunlop” used for the immersion and retreading of rubber tyres, and costumes worn for the blessing of vehicles ahead of an MOT.

Bove’s attention to the dowdy aesthetic of local museum displays, and the language of their signage is immaculate. From “historic” photographs of dancers in pearl-buttoned costumes that apparently prefigure motorway engineers’ hi-vis, to field recordings of “traditional” chants, the whole presentation is so thought through and deadpan that it is hard not to believe it’s real. This muddying of the waters is affectionate but pointed – in the world of folk custom, the distinction between ancient tradition and recent invention is seldom a sure one. The past for which nationalist politicians invite our nostalgia is as much a creation as the artefacts in Bove’s museum.

The Museum of Roadside Magic is parked beside a small industrial estate, but other locations are more picturesque. A glowing haystack occupies the 15th-century great hall of the manor house, perfectly echoing the arc of its gothic roof. Illuminated by ultraviolet light and smelling sweetly of the field, Simon Lee Dicker’s Red Hot Haystacks nod to the territorial intersection of agriculture and the military. In Orkney in the 1960s, cumulative contamination by atmospheric nuclear tests became evident once hay drying in the field was gathered in stacks.

Beyond the wellies in the manor’s entrance hall plays Adam Chodzko’s The Pickers. Chodzko commissioned four Romanian migrant workers – then engaged in harvesting strawberries in Kent – to view and edit archival film of crop-picking. Images on screen flip between early 20th-century documentation of workers on stilts setting up twine frames for hops, jolly families pulling the flowerheads off the resulting vines, and groups of Londoners gathering Kent harvests on a working holiday. The Romanians, who were recorded while editing, are fascinated by these bygone visions of contented labour and liken them to the collective farms of the Ceaușescu era.

Their own workplace more closely resembles a factory or laboratory than a picture-book farm. Within the tightly regulated climate of a plastic-roofed shed, strawberries grow in elevated beds from which stems full of fruit dangle for harvesting. “Imagine in the future that the British come to Romania to work in one of your companies because their economy has collapsed,” fantasises one of the pickers. “They would have nothing to do in their own country. It would be interesting if they came to us. I would like it.”

International relations of a different kind are imagined by Emii Alrai, whose dioramas of ersatz archaeological fragments are arranged in a long loft first used for the fabrication of ropes. West Coker was once famous for its rope and sail-making, connecting the village to the fortunes of Britain’s imperial and merchant fleet. Alrai’s half-buried pots and shards imagine the cultural plunder that occurred along these voyages, linking distant soil back to the Somerset fields that grew the flax that made the rope.

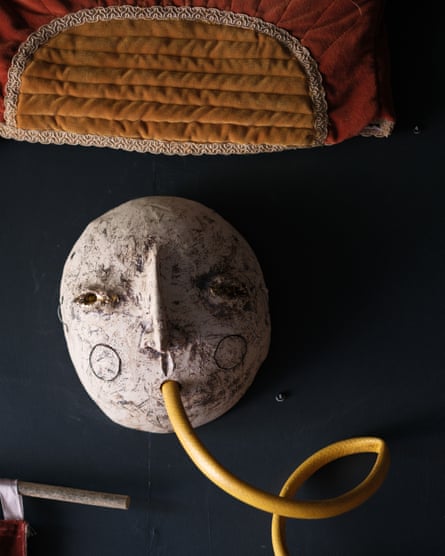

More esoteric works occupy the cemetery chapel. Arranged in an inward-pointing circle, the ceramic hands of Chantal Powell’s A Summoning, sprout ears of corn like tiny flames and carry engraved emblems of woven corn stalks. Its blend of ancient symbols suggests uncanny power. You might think twice before standing at this circle’s centre. Ella Yolande’s Find Us in the Slip Spaces is a gauzy suspended archway embroidered with pouches of fragrant herbs, leaves and seedheads. In this place of transition between life and death, it hangs as a symbolic (or perhaps hopeful) portal between realms.

.png) 3 months ago

63

3 months ago

63