The documentary film-maker James Bluemel has a technique that is more radical than it sounds: he lets the people who were there at the time do the talking. His preference for frontline witnesses, rather than decision-makers who wielded influence from afar and have reputations to protect, has previously enabled his Once upon a Time strand to show unique perspectives on Iraq and Northern Ireland.

Political discourse often forgets how conflict defines or destroys the lives of the innocent folk it touches, so it’s easy to see how those testimonies have value – and Once upon a Time has ended up offering big-picture analysis via their mosaics of personal experience. How will that work, though, with space exploration … an extraordinary activity only a select few choose to pursue?

Once upon a Time in Space gets there, but it takes time to acclimatise to it. You expect a space documentary to be expansive and majestic; this is restrained and domestic. It starts by skipping quickly past Yuri Gagarin, Neil Armstrong and the first wave of explorers – although a clip of a ticker-tape parade for the returned Apollo 11 crew is one of many fabulous finds from the archive – and concentrates on the Space Shuttle programme, starting from the late 1970s.

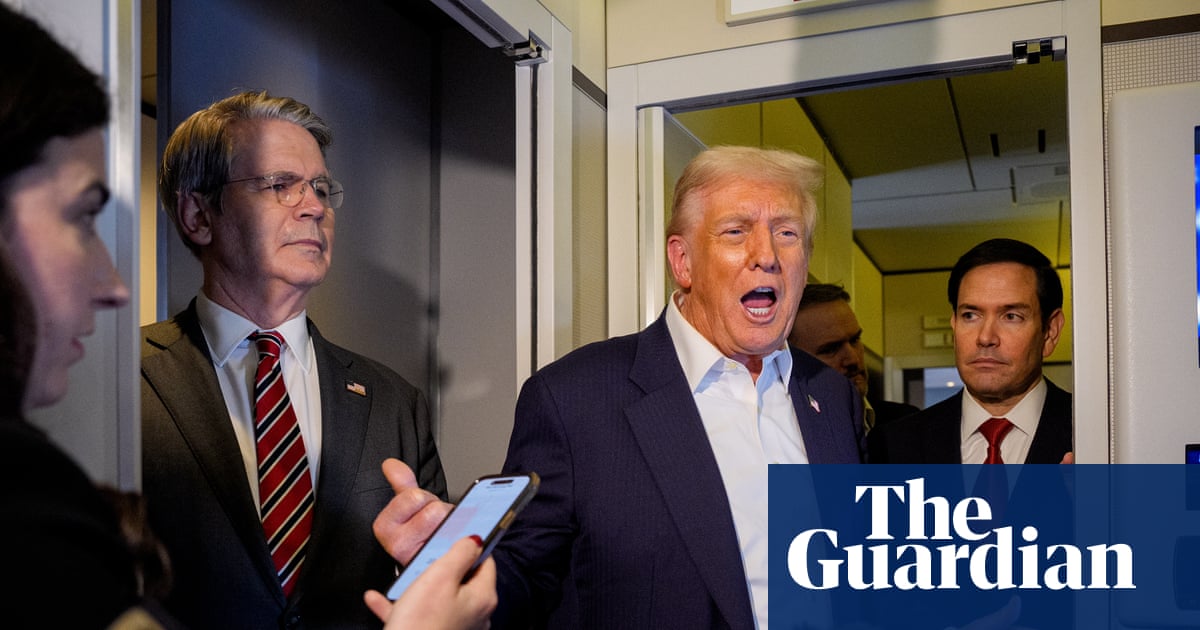

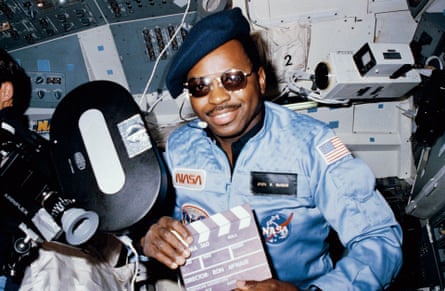

Two families dominate, each reflecting how the shuttles ended the dominance of white male astronauts. Anna and Bill Fisher marry in 1977, as they are going through the Nasa selection process: Anna gets in first. The birth of their daughter, Kristin, in 1983 means Anna becomes the first mother in space when she completes her initial mission the following year. Entering the shuttle programme at about the same time is Ronald McNair, an African American man whose impoverished upbringing in segregated South Carolina makes him an unlikely spaceman: “There were no Black people doing that,” says McNair’s brother Carl, his representative in this programme. “That wasn’t our world.”

Ronald McNair’s story is one of triumph, as his excellence sees him ascend to the top of the space programme and his dashing demeanour – plus a generous spirit that prompts him to directly encourage other Black Americans to put aside their preconceptions of Nasa and get involved – turns him into a beloved celebrity. There is a wonderful clip of the McNair brothers’ dad, car mechanic Carl Sr, speaking with uninhibited pride about Ron to a TV news crew: “I just wish every father could have a son like I have!”

Fisher’s pregnancy, however, provokes wearingly familiar sexism from the press: “Is she a good mother?” asks a 1984 newspaper article, read aloud at the time by Fisher herself. “That will be the question on millions of minds when the first astronaut mother goes up, leaving a year-old daughter behind!” That one-year-old is now CNN journalist Kristin Fisher, who is also interviewed: “It’s a fair question,” she says, “but it’s also a question that people aren’t asking the men.”

The Fishers also speak about family life in the shadow of their parents’ risky vocation: Bill and Anna were told by their employers that there was an expectation that one in every 25 launches would fail. “How many other professions have an actual countdown clock to the moment when you might perish?” says Kristin. The episode is, of course, building towards January 1986 and the launch of Challenger, which explodes soon after takeoff and kills all seven astronauts aboard – including McNair. His brother Carl recalls how bewildering it was for the instant of a loved one’s death to be a global news event: “It was all over every station, over and over and over again. My brother dying.”

Interesting and affecting as these memories are, they are more a case of relatable experiences – overcoming self-doubt to chase a dream career; growing up unaware of the hard choices one’s parents are facing; grieving for a family member suddenly lost – made remarkable by their unusual context, rather than the regular Once Upon a Time trick of making a complex political situation more comprehensible by showing us its simpler details. The three remaining episodes will look through a wider lens, investigating how America and Russia ended the space race by going into orbit as a joint venture, with those aboard the Mir and International Space Stations enjoying collaborations that turned enmity between superpowers into an absurd concept – until aggression down on Earth made those celestial relationships unsustainable.

The more fundamental message is the one contained within Armstrong’s line about man and mankind: this handful of humans, with their ambitions and emotions not much different from anyone else’s, did something incredible on humanity’s behalf. Once Upon a Time in Space opens with a caption reminding us that an era of mass space travel might soon arrive – but watching this, the cosmos already feels a little closer.

.png) 5 hours ago

3

5 hours ago

3