Of all the professionals who studied Axel Rudakubana before his murderous attack in Southport last summer, the notes of a rookie police officer in 2019 may be the most prescient.

The actions of Rudakubana, then aged 13, showed “potential for huge escalation”, wrote PC Alex McNamee after spending just 20 minutes with the teenager when he admitted taking a knife to school to attack a bully. The risk, he wrote, was “high”.

Yet by July 2024, six days before his knife rampage, Rudakubana had been discharged from mental health services after five years with a perfunctory report that concluded: “Poses risk to others – None.”

The failures that left Rudakubana, then 17, able to murder three young girls – Bebe King, six, Alice da Silva Aguiar, nine, and Elsie Dot Stancombe, seven – have been scrutinised by a public inquiry that concluded on Thursday. The inquiry chair, Adrian Fulford, is expected to deliver recommendations to the government by spring.

After nine weeks of evidence from more than 100 witnesses, the Guardian can identify some of the key ways Rudakubana fell through the gaps with tragic results.

Parental failure

Over two days of astonishing testimony, Alphonse Rudakubana, the killer’s father, admitted knowing that his son had amassed an arsenal of weapons – including knives, a bow and arrow and a sledgehammer, as well as a jerry can – and that he feared his son was planning to attack others.

Yet he did not alert the police, or any other agency, because he worried his son would be taken away.

Alphonse, 50, told the inquiry he was left terrified, abused and repeatedly violently attacked by his teenage son. Their relationship disintegrated to a point where Alphonse, given asylum in Britain after the Rwanda genocide, was too scared to curb his son’s troubling internet activity or stop his orders of knives.

The inquiry heard how Alphonse and his wife, Laetitia Muzayire, had sought help for their son as early as April 2019, when his troubles began aged 12. But their relationship with professionals deteriorated as Rudakubana became more violent.

Alphonse was likened to a “keyboard warrior” as he sent repeated “verbally aggressive” emails to schools, social workers and psychologists and routinely accepted his son’s version of events, despite mounting evidence of the danger he posed.

By 2024, the family had effectively disengaged from all support as a mutual distrust deepened. They felt failed by the system, they said. At home, they allowed him to fester in dark places online for fear of triggering one of his many violent reactions.

Rudakubana had not left the house for more than two years before the Southport atrocity, spending his time amassing weapons, including machetes and other knives for which his father took delivery.

On 23 July 2024, seven days before he murdered the three girls, Alphonse stopped his son from taking a taxi to his former school, from where he had been permanently excluded nearly five years earlier. He was carrying a knife and asked his father to buy petrol for his jerry can.

The parents admitted to the inquiry they knew by then he was planning an attack. Yet they failed to alert the police or any other agencies. This, Alphonse admitted, had “catastrophic consequences for which I am desperately sorry”.

The tech companies

Six minutes before he left home for his lethal attack, Rudakubana searched X, formerly Twitter, for a video of the stabbing of Bishop Mar Mari Emmanuel at a Sydney church in April 2024. The teenager had multiple accounts on the platform yet there are no restrictions as to what under-18s can view.

Giving evidence as to why such “horrific” material remained freely available on X, its head of global government affairs, Deanna Romina Khananisho, told the inquiry that removing it “isn’t justice, that’s tyrannical overreach”.

Rudakubana used Amazon to buy the 20cm knife used in the attack for £8.39 two weeks earlier. His search history on the site contained axes, secateurs and bill hook knives. He went on to buy smoke grenades, a sledgehammer, castor seeds and equipment to try to make the poison ricin, some bought using false names and with a VPN to disguise his identity.

Giving evidence, an Amazon executive, John Boumphrey, said the company was able to analyse suspicious purchases and report them to authorities – but that it “typically wouldn’t do that”. Rudakubana used his father’s details to pass age verification to buy the knife he used two weeks later.

“It would have been, quite literally, child’s play to pass [these checks],” the inquiry counsel, Richard Boyle, said. Boumphrey accepted it had been too easy and that Amazon had “made a number of changes very swiftly”.

System breakdown

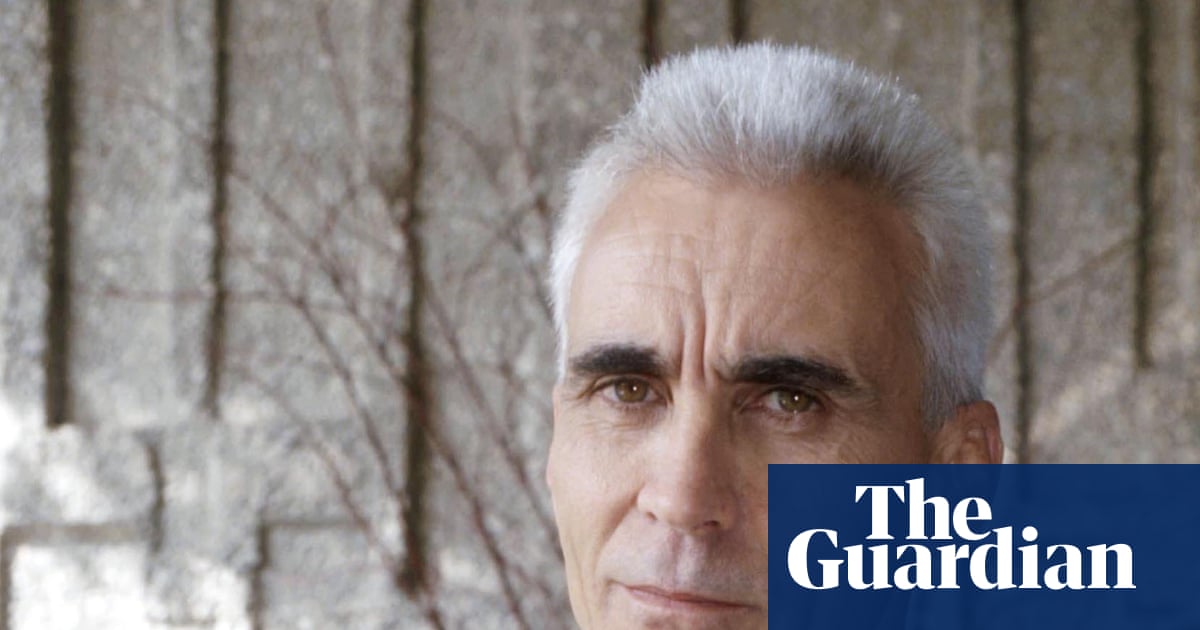

The inquiry chair, Fulford, described the atrocity as a case of “wholesale failure” by multiple institutions. “Far from being an unforeseeable catastrophic event,” he said, Rudakubana posed a “very real and significant risk of harm” owing to his known history of knife crime.

Perhaps one of the biggest questions is why in the five years the teenager was under treatment he was never seen by a forensic psychiatrist who could have properly assessed his risk.

In October 2019, aged 13, he was permanently excluded from the Range school after admitting taking in a knife on a number of occasions and planning to attack a bully. This was when PC McNamee assessed that he had “potential for huge escalation”.

Three months later, he was arrested after returning to the school and seriously assaulting another pupil – not the bully, who he could not find, but an innocent student Rudakubana later said he actually liked. He had been armed with a knife and a hockey stick.

Attempts to have Rudakubana assessed for autism got stuck in the NHS backlog. He was not officially diagnosed until December 2020 – a whole 77 weeks after the first GP referral and despite attempts by teachers and others to progress it more quickly.

This was significant because it meant he could not have a forensic risk assessment by Alder Hey’s child and adolescent mental health services, which requires an autism diagnosis. This meant, the bereaved parents said, that violent episodes were treated as isolated incidents rather than a trajectory towards more serious harm.

The inquiry was told there was sufficient evidence by September 2023, nearly a year before the attack, that Rudakubana met the conditions for an assessment under the Mental Health Act. This would have assessed his risk and possibly resulted in hospital treatment, but it never happened.

There were multiple examples heard by the inquiry of a lack of information sharing between agencies. Because Rudakubana was under 18, there was no formal meeting of a multi-agency public protection arrangements team, which usually involves police, social services, probation and others discussing high-risk cases.

The anti-radicalisation scheme Prevent was also scrutinised. Rudakubana was referred three times to the programme between December 2019 and April 2021 for researching potentially extremist material at Acorns pupil referral unit. Each time the cases were closed.

Prevent officials told the inquiry that this was a mistake and that he would have been referred for further support had they been aware of the teenager’s wider internet history; a third referral should automatically have triggered further action.

The Prevent officer who closed Rudakubana’s first two referrals said she felt other agencies were better placed to address his needs but that “there may have been a failure for information sharing”. She added: “I felt that nobody really had responsibility for him or felt that they had responsibility.”

Another flaw was that frontline police officers were not able to see Rudakubana’s Prevent referrals. Had this information been shared, action may have been escalated when he was found on a bus with a knife in March 2022 saying that he wanted to stab someone and that he had an interest in making poison. Instead, police officers returned him home and advised his parents to hide their knives.

Gaps in the law

The Terrorism Act makes it a criminal offence to withhold knowledge of plans to commit an act of terror. But there is no equivalent law for when someone is preparing an attack unconnected to ideology.

Rudakubana did not have a defined extremist motive – he downloaded reams of anti-Islamic material alongside antisemitic, sexist and graphically violent images – but his history of carrying knives as a weapon was well known and his father knew by early 2024 that his son was ordering weapons online. A legal duty to report this to police may have focused minds.

Fulford will assess whether the state should have new powers to impose restrictions on individuals when there is strong evidence they intend to carry out an attack but not enough to justify an arrest. Such a move is likely to be opposed on civil liberties grounds but the prime minister, Keir Starmer, has said “nothing is off the table” to prevent a repeat of 29 July 2024.

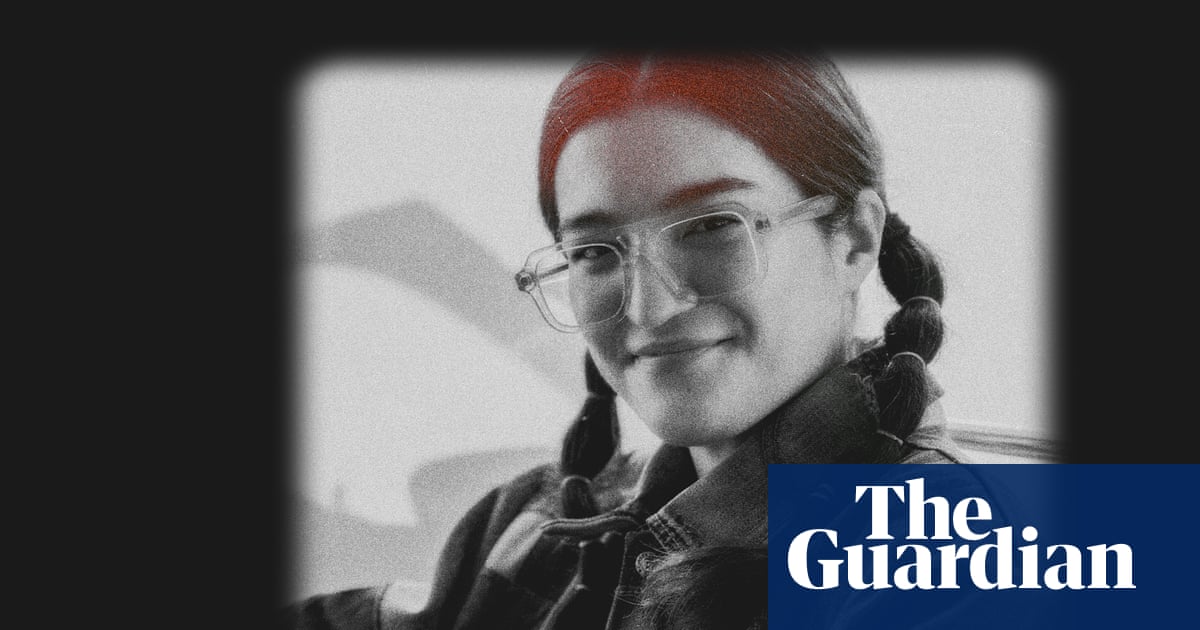

After nine weeks of evidence, it is clear that many of those who had responsibility for Rudakubana must share the burden of blame. As Alice’s parents, Alex and Sergio Aguiar, said this week: “This tragedy was not inevitable. It was the result of neglect – neglect by those who should have known better and by a system that repeatedly ignored warning signs.”

.png) 2 hours ago

6

2 hours ago

6