Thirteen ambulances are lined up at the rear of the Emergency Department (ED) of the Royal Stoke university hospital, Staffordshire, as Ann-Marie Morris, the hospital trust’s deputy medical director, walks towards the entrance, squinting in the low afternoon sun. Behind the closed door of each vehicle is a sick patient, some of whom have been waiting for four hours or more, backed up in the car park, just to get in the door.

The reason they are stuck out here is that there are no beds in the ED – and there is not much corridor space, either. In the tight foyer, a cluster of ambulance staff and a senior nurse in hi-vis are huddled around a computer station. Behind them, a corridor stretches into the ward, where at least six or seven beds are lined up head to toe along one side, each occupied by a patient. Leading off to the left are three more beds and three more strained, watchful patients. Another patient and another bed is to the right.

“So … this is busy,” says Morris. “This is not our worst day, but equally … it is a challenge to manage, I would say, today.”

It has been a day of huge logistical headaches and considerable personal stress for those working at this large regional NHS hub. The Royal Stoke is absolutely full, with every single usable bed from its total of 1,178 occupied, and a few more besides (as well as the 15 patients being treated in corridors in the ED, 20 more are in the same position in wards elsewhere). The hospital’s Operational Pressure Escalation Level (Opel) risk level stands at 4, the highest possible designation before it would have to declare a critical incident – meaning it could not necessarily deliver all of its services safely.

In other words – it is just another winter Tuesday in the NHS. Britain’s national health service is under exceptional pressure this week, with an unprecedented early rise in flu cases, rising to the highest case numbers recorded for this week in December, colliding with a five-day strike by resident doctors which began on Wednesday. It has led to apocalyptic language from some health leaders about this year’s “worst ever” winter crisis, warning of a “flu-nami” that one A&E consultant described as a potential “armageddon”.

For the battle-hardened staff of the Royal Stoke, however, these appear to be just two further complications – significant and unwelcome as they are – in what is already an exhausting “permacrisis”. Yes, winter brings huge challenges, but “it would be fair to say I don’t think we’re ever out of winter,” says Dan Hobby, matron for general surgery. “It almost feels like winter is 12 months a year. We are permanently in winter.”

The Guardian has been invited by the University Hospitals of North Midlands trust to spend a day at the Royal Stoke, speaking to staff about how they care for patients while grappling with the sometimes more complex task of managing their progress through the gridlocked system – one bed at a time – to clear a space for others.

Staff in wards across the hospital speak frankly about the hourly challenge of trying to meet huge demand with beds that are definitely finite. Patients praise the care they are receiving from resourceful, dedicated, tired medical professionals.

The hospital is not keen to share everything, however. We are stopped at the door of the Emergency Department and steered away from the crowded area where people are being treated in the corridor. Photographs are out of the question. Corridor care has long been a common practice at many hospitals, but the brutal reality of the NHS’s beds crisis can feel too distressing to expose to others.

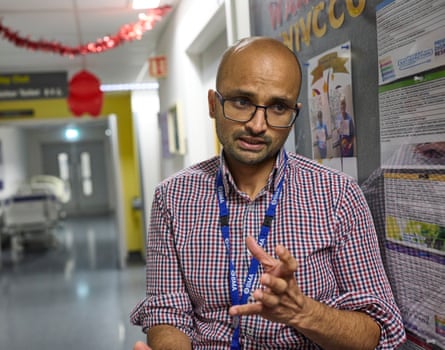

In a tinsel-festooned respiratory ward on an upper floor, Dr Ashwin Rajhan is meeting Raymond Dutton, a 74-year-old former police officer who has motor neurone disease. Dutton has a tracheostomy tube which allows him to breathe but hampers his speech, so he communicates gamely with smiles gestures and by writing on a smart phone, while the machine keeping him alive hisses in the background.

Rajhan, one of 18 respiratory consultants, says the flu spike presents a particular risk for vulnerable patients such as Dutton, which has put side rooms where patients can be isolated at a particular premium across the hospital. “We are seeing quite a number of flu patients, but thankfully, not many are needing critical care admissions,” says Rajhan. The disease’s surge has definitely been a problem in the region – on 6 December, the hospital along with five others in the west Midlands declared a critical incident over admission numbers – but in the past fortnight “we seem to have plateaued”.

The big question is whether an early surge means this winter’s flu will blow over earlier or, as many in the hospital suspect, lead to a second increase after families gather for Christmas. Either way, when the ward is full but beds are needed, resourcefulness is required.

“Today was a good example,” says Rajhan. “When we came in the morning, we were told that there were four patients in ED who needed to come to this ward because they needed NIV [non-invasive ventilation].” The 28-bed ward has an NIV capacity of 20; they were already at 21. “So we had to go through all the patients individually, get the physios on board and ask them to see the patients urgently” to get them in a place to leave.

The ward’s computers were not working, slowing the process of discharge. “One of the discharge facilitators has physically gone down to another part of the building, dragged the IT person up and as we speak he is replacing all the computers.” Every bed the consultant cleared meant another person could be moved from ED, emptying another ambulance and allowing another very unwell person to be collected by paramedics and brought to the hospital for the process to begin again.

Such individual bursts of initiative sit alongside a range of levers that clinicians can pull to release steam from the overheating system. “Admission avoidance techniques” include “hot clinics”, where patients are seen as outpatients, and CRIS, a community response team that visits patients’ homes to pre-empt emergency admissions. In the hospital, a process called “In-Reach” sees specialist staff from one ward consult patients who have been stuck on another because there is not room for them. After discharge, “virtual ward” sees patients visited at home to follow up on their hospital care.

But institutional gridlock remains one of the hospital’s biggest challenges. On the critical care ward, a major trauma unit whose patients include those who have had cardiothoracic surgery, Tracey Wootton has been waiting for transfer to a general medical ward. The national standard to move patients like her on is four hours; Wootton has been here since Saturday, three days ago.

It’s a similar picture on the surgical assessment unit, which covers specialties ranging from ENT to gynaecology. Since being forced to surrender a ward to another department in October, patients now wait three days for a transfer rather than 24 hours. The SAU is a “chaired” unit, meaning patients are assigned loungers. Its capacity is 30; it currently has 55 patients. “So unfortunately patients end up on plastic chairs as well, which isn’t ideal,” says senior staff nurse Molly Merrison.

Senior staff have been sanguine about the resident doctors’ strike, the 14th such walkout in their long-running dispute; others, though, say the impact will be “massive”. “I think from a discharging perspective, because it’s all on computer systems now … how do I put this … if you haven’t got your regular staff they might not know exactly what needs to be done,” says one senior nurse. In other words, the consultants do not know how the computers work to get patients discharged.

“It is a learning curve, I can’t deny that,” smiles respiratory consultant Rajhan, “but equally, I find it easier to pick up the phone and speak to another consultant colleague in another department. Yes, I might take more time going into the computer system to type, but the decision to reach that point is much quicker.”

While clinical procedures and treatment decisions have been ongoing all day, in a windowless room at the heart of the hospital, clinical head of operations Becky Ferneyhough and colleagues from the site operations team have been sitting under large computer screens (and strings of fairy lights), monitoring a series of graphs that are measuring the shifting capacity and flow of patients through each ward and hospital department, to allow decisions to be made about moving resources where needed.

Four times a day, she meets senior colleagues from across the trust; at the 8.30am meeting on Tuesday, 12 ambulances were waiting outside the ED, one of them for 6 hours; by lunchtime it was eight. We check in again after 5pm. “We have 20 ambulances outside,” says Ferneyhough. “We’ve had a very difficult afternoon.”

It must be stressful having these conversations about numbers and resources, when we are talking about real people. “Absolutely, 100%,” she says. “The patient is the most important part of everything that we do and it really is hard work to balance doing the right thing for the patient – but for all of our patients.

“It’s not just the patients we’ve got in the hospital, it’s the patients who will be our next patients, who are at home waiting to come in to the hospital. Some of those decisions are really, really difficult to make.”

.png) 2 months ago

42

2 months ago

42