A groundbreaking Trinidadian-British playwright who paved the way for modern Black British theatre makers warned about the dangers of gentrification in Ladbroke Grove, which he believed would ruin the “writer’s paradise”.

Mustapha Matura was the first British writer of colour to have work put on in the West End, and used the west London area as an inspiration for many of his plays, which were also staged at the Royal Court and National Theatre.

In a letter written in 1992 that is part of the Matura archive acquired by the British Library, he decried the shifts in the west London area, which was home to a strong Caribbean creative community.

“What more could one ask for?” he wrote about the area. “It’s like being in a real-life, long-running soap opera, which I tell myself I’m only researching in order to write about but – not true … I’m a character and a ‘writer fella’ who prays that the gentrification process that is taking place in the area now does not totally destroy its unique character and characters.”

The bohemian area that Matura found in the 60s and 70s has certainly changed, more synonymous now with rising house prices than creative freedom. In 2024, it was reported that residents of Notting Hill received more in capital gains from 2015 to 2019 than the combined populations of Liverpool, Manchester and Newcastle.

The son of a south Asian man and a creole woman, Matura left Trinidad for the UK in the 1960s. He worked as a hospital porter, frequented the Royal Court and ended up appearing in a B-movie western shot in Rome.

It was in Italy where he saw a production of Langston Hughes’ Shakespeare in Harlem and thought he “could do better than that”, and began writing.

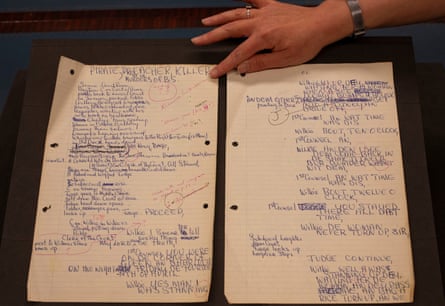

Like other Caribbean playwrights, Matura had a side job while getting his footing, working in a garment factory off Tottenham Court Road. He would jot down ideas and doodles on the back of order sheets, some of which have been retained in the archive.

Matura’s wife, Ingrid Selberg, said: “He was supposed to be counting the rolls of material, and he was always skiving off and writing things on the back of the order forms.”

Described by one writer as looking like “a refugee from a 60s band” who wore sunglasses indoors and sported a “morose walrus moustache”, Matura fit into the countercultural world of Ladbroke Grove.

He was a key part of a flamboyant group of Caribbean creatives who injected black consciousness into UK culture, along with Horace Ové (who directed the first Black British feature film, Pressure) and Michael Abbensetts (who went on to create Empire Road).

Helen Melody, the lead curator of contemporary literary and creative archives at the British Library, said: “I think he was aware of the political uncertainty and uprisings of the whole movement in the 1960s, which wasn’t just in Trinidad but more widely.

“You can see his plays often chart the experience of people who’d traveled to the UK or elsewhere from the Caribbean, but he also still retained kind of an interest in what was happening in the place he left as well.”

The archive contains unpublished work including two plays, one called Band of Heroes about Notting Hill carnival and the other about the real-life Trinidadian gangster Boysie Singh.

Despite having no formal training, Matura became arguably the most significant playwright from the Caribbean diaspora in the 20th century.

He was a founding member of the Black Theatre Co-operative, which was formed by a group of actors who had appeared in his 1979 play Welcome Home Jacko, while his first agent was the formidable Peggy Ramsay.

Matura died in 2019 and a funeral was held in Ladbroke Grove, with a steel band sendoff.

“He was such a Trinidadian,” said Selberg. “But he loved Ladbroke Grove, he loved Portobello Road. He was a kind of Janus with a two-sided head. Interested, equally interested in both Britain and Trinidad, and equally critical of both.”

.png) 2 months ago

39

2 months ago

39