On the Death of Dr Robert Levet by Samuel Johnson

Condemned to Hope’s delusive mine

As on we toil from day to day,

By sudden blast or slow decline,

Our social comforts drop away.

Well tried through many a varying year,

See Levet to the grave descend;

Officious, innocent, sincere,

Of every friendless name the friend.

Yet still he fills Affection’s eye,

Obscurely wise, and coarsely kind;

Nor, lettered Arrogance, deny

Thy praise to merit unrefined.

When fainting Nature called for aid,

And hovering Death prepared the blow,

His vigorous remedy displayed

The power of art without the show.

In Misery’s darkest cavern known,

His useful care was ever nigh,

Where hopeless Anguish poured his groan,

And lonely Want retired to die.

No summons mocked by chill delay,

No petty gain disdained by pride,

The modest wants of every day

The toil of every day supplied.

His Virtues walked their narrow round,

Nor made a pause, nor left a void;

And sure the Eternal Master found

The single talent well employed.

The busy day, the peaceful night,

Unfelt, uncounted, glided by;

His frame was firm, his powers were bright,

Though now his eightieth year was nigh.

Then with no throbbing fiery pain,

Nor cold gradation of decay,

Death broke at once the vital chain,

And freed his soul the nearest way.

This elegy by Samuel Johnson (1709-84) has always been one of my favourite poems in the genre. It forms a very small part of Johnson’s magnificent literary achievement, and its scope is unambitious. What it succeeds in doing, as an elegy closer in style and diction to an 18th-century “occasional” poem, is a kind of mimesis: it adds up to a portrait of the admirable Dr Levet. We’re not merely told about him but given a physical presence in the tropes and rhythms of the verse.

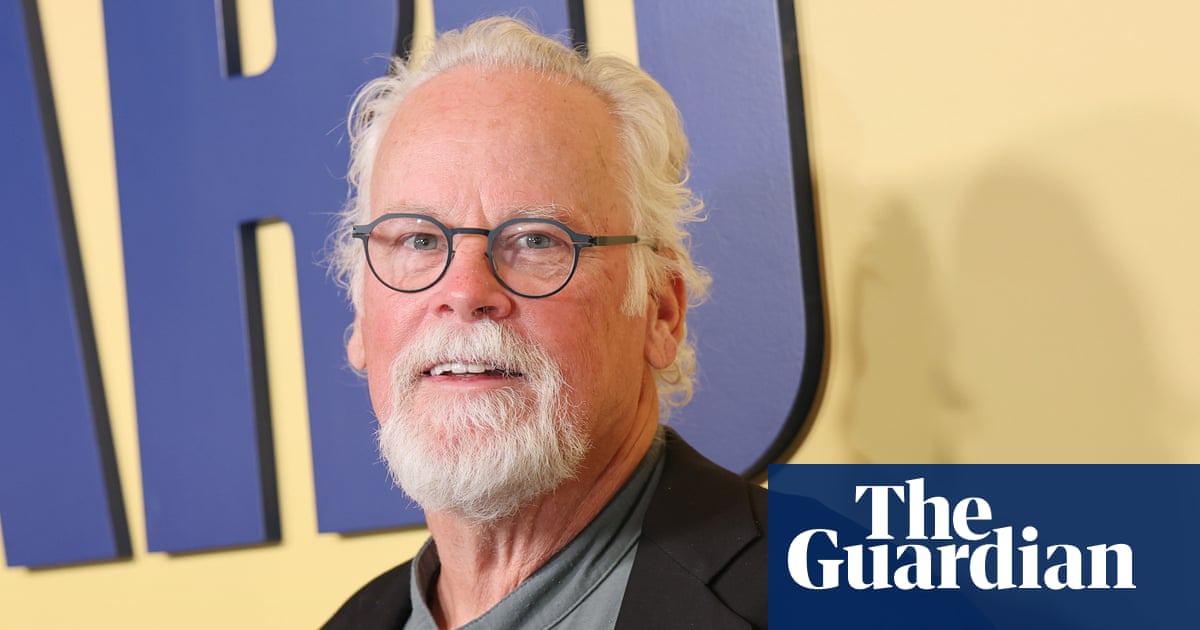

The Hull-born Robert Levet (1705-1782) had lived in Johnson’s household from the later 1740s. He had become interested in medicine when, working as a waiter in Paris, he listened in, fascinated, to the doctors’ conversations as they dined. It seems a subscription was made for him to receive some training in pharmacy and anatomy. He remained unqualified, and, in London, his practice was among the poor. He worked for very small or no remuneration. As Johnson’s personal physician, he was deeply trusted by his master.

Johnson’s recourse in the elegy to allegorical figures (“Hope’s delusive mine”, “Misery’s darkest cavern”, “lonely Want”, “lettered Arrogance”, to list a few) is relentless; the poem isn’t capacious enough to allow them to be explored and most may pass quicker through the reader’s mind than they deserve. However obvious-seeming, they are often rich in allusion - Want, for example, having been deserted by the friends that Wealth would, presumably, have easily kept, is revealingly “lonely”. Hope as a “delusive mine” is a powerful image allotted more generous space: the vicissitudes of the perilous activity (mining) are seen in realist terms, involving “sudden blasts” and “slow decline”. Metaphorically, they connect to Johnson’s own failure of hope, and the demise, abrupt or gradual, of his “social comforts”, so placing Robert Levet among the household companions Johnson deemed essential to his mental and physical wellbeing.

It’s illuminating to see, in the torrent of verbal virtuosity gathered on Wikiquotes, James Boswell’s report of Johnson’s words on “hope” as “perhaps the chief happiness this world affords … but expectations improperly indulged must end in disappointment …” . Johnson’s first quatrain here centres on a hope that is based on his wants rather than their possibility. It’s the forlorn hope that death is avoidable.

Levet himself has been “well tried through many a varying year”. The rhetorical imperative, “See Levet to the grave descend” seems to denote both shock and fulfilled expectation. It also mocks any elevated poetic or biblical connotations of death. A thumbnail sketch of Levet the man follows: it sets out his qualities, with a touch of loving exaggeration, as “officious” (dutiful), “innocent, sincere / Of every friendless name the friend.” The contradictory nature of the man is condensed in the oxymoronic line “obscurely wise, and coarsely kind”. Johnson’s words to Boswell are more directly revealing: Levet is “a brutal fellow, but I have a good regard for him, for his brutality is in his manners, not in his mind”.

It’s in the sixth stanza that Johnson most effectively characterises Levet, by contrasting him tacitly with doctors of higher training and aspirations: “No summons mocked by chill delay, / No petty gain disdained by pride, / The modest wants of every day / The toil of every day supplied.” This is one of the more elegant stanzas, visualising perhaps the gracious disdain of the higher-ranked physicians, but the lines are still firmly end-stopped and modestly cadenced. Johnson’s ABAB-rhymed tetrameters tramp steady circles throughout the poem, suggesting the regular, heavy tread as Levet makes his rounds, serving his patients with skill and care, but no inessential flourishes.

In the last stanza, Levet’s demise is treated without special ceremony. The merciful swiftness of the death, apparently from heart attack, urges no pious sentiments from Johnson. His technique is as matter-of-fact as Levet’s medical learning. “Death broke at once the vital chain / And freed his soul the nearest way”. The undoing of a prisoner’s shackles is suggested in that gruff, unemotional language and rhythm. If the closeness of the soul to the mythical organ of love, the heart, is implied, Johnson makes little of the point.

On the Death of Dr Robert Levet combines accomplished technique with resistance to the florid elegiac manners of Johnson’s period. It does its subject the greatest honour not by characterisation alone, but by being made in that character’s image.

.png) 4 hours ago

4

4 hours ago

4