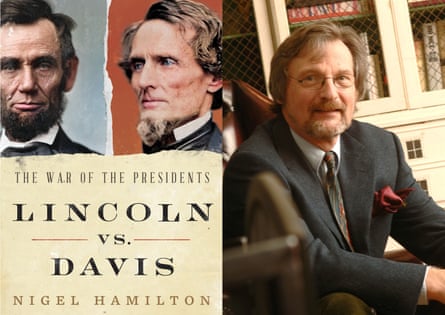

Nigel Hamilton is a bestselling biographer, his major subjects including John F Kennedy, Franklin D Roosevelt and Bill Clinton. His new book, Lincoln vs Davis: The War of the Presidents, was published on Tuesday, the US presidential election day when Kamala Harris faced Donald Trump.

Late in his book, Hamilton notes a harsh 1862 verdict on Washington life by Adam Gurowski, a Polish emigre in the state department, anguished words that seem relevant and pungent today.

“The political cesspool is deeper, broader, filthier and more feculent than ever,” Gurowski wrote.

Gurowski had reason to be disgusted. In December 1862, the union stood in peril. Days earlier, at Fredericksburg in Virginia, northern forces were routed. The Emancipation Proclamation, which would formally change the war into the fight to end slavery radicals wanted, had not yet come. For the forces of progress, it was a dark moment indeed.

Hamilton’s book is a product of another dark moment. He began work in 2019, when Trump was president, the White House a stage for chaos. Five years later, Lincoln vs Davis was released the day Trump returned to power, after a campaign strewn with allegations of fascism, the states of the Confederacy behind him, the US as divided as at any time since the civil war.

Speaking a day before election day, Hamilton said his dual biography of Lincoln and Jefferson Davis, the Confederate president, was “fascinating to write at this historical moment. We’re pretty much facing the same situation as Lincoln over 160 years ago. He wins an election and the results of the election are not accepted by half the country, and they actually resort to armed insurrection. We had a kind of inkling of that on January 6 2021,” when Trump sent his supporters to storm Congress.

“Now … many people are nervous about violence and insurrection yet again. What did Karl Marx say? History repeats itself, first as tragedy, then as farce. Well, it has been repeated, the Lincoln election, on January 6, rather tragically. Will it be farce in the coming days? I don’t know, but it’s sort of strange to have written this book and then to have seen, in a sense, it all coming alive again.”

Harris has accepted defeat. Four years ago, Trump did not, fighting through the courts and Congress, before and after his supporters attacked. Hamilton’s book, though, was born on an actual battlefield.

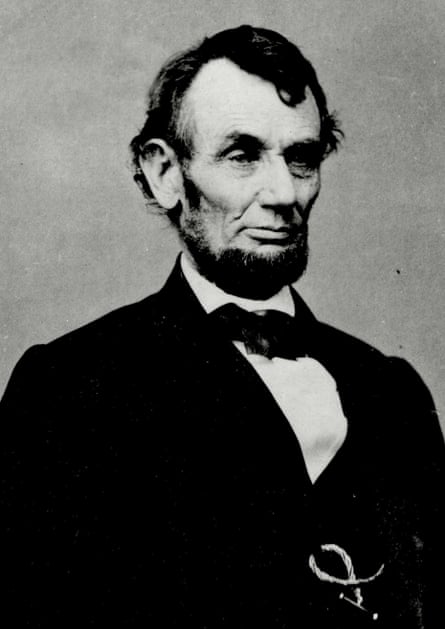

Having spent childhood summers on the battlefields of Normandy, where his father commanded British forces in the second world war, and more recently “spent 10 years on Franklin Roosevelt as commander-in-chief” in that same war, Hamilton “was giving a talk about the final volume, War and Peace, at Gettysburg, and I took a young historian friend around the battlefield, which is a very moving place. And I looked at him and I said, ‘Lincoln at War’. I had developed this lens, if you like, for looking at a president who may not be trained as a soldier, how he conducts himself, because … it is a unique role that every president takes on and if it does involve war, it’s extremely taxing and a terrific challenge.

“So I went to my publisher and said, ‘I’d like to to use that FDR lens on Lincoln.’ There had been several very good books, but they’re all written by historians. They’re not written by biographers,” practitioners of an art Hamilton boils down to “trying to get into the mind” of the individual at hand.

“So I started the work with some confidence, but … I very quickly realized that I was writing the wrong book. That there had been 20,000 books about Lincoln, every aspect of Lincoln, but nobody had ever actually studied how he ran the civil war as commander-in-chief against his opponent.”

Davis, who tried to save slavery, is no national hero now. But he was then, as a soldier, in the Mexican-American war; as a politician, as a senator from Mississippi; and as an administrator, as secretary of war. In broad outline, Hamilton’s study of the two men shows how Davis first got the better of of his inexperienced rival, a country lawyer with brief military service who spent one term in Congress, only for Lincoln to adapt, learn and survive, ultimately to gain the upper hand.

To Hamilton, writing a joint biography was in some respects “like recording a boxing match, and that’s not a bad analogy, because very early in the war there was a wonderful cartoon which I put in the book where Lincoln’s standing in boxing shorts and he’s got his fists up and he’s facing Jefferson Davis.

after newsletter promotion

“The conflict between them really is like watching two boxers, one of whom is virtually untrained, who’s very gangly, though he has his own talents, and the other one has been trained to be a boxer, who’s extremely competent, and damn nearly wins the war within a year and a half.”

To Hamilton, that Davis did not defeat Lincoln was largely the result of hubris: in the person of Robert E Lee, the Confederate general who took the war north in 1862, and in Davis’s failure to stop him. Once the Confederate claim to self-defense was lost, Lincoln could play his strongest card: emancipation. Once the war became a war to end slavery, accepted by enough of the north, so the south lost hope of recognition by foreign powers hungry for cotton. Hamilton’s book ends on 1 January 1863, with the Emancipation Proclamation. The war dragged on two more years but the die was cast.

To Hamilton, “the greatest thing about Lincoln” as president “was that he did believe in the consensus of the cabinet, of bringing the cabinet with him, of not expelling people even when they made mistakes. So from a kind of executive point of view, he was weak. I call him at one point vacillator-in-chief. He can’t make up his mind and worse, he can’t get rid of people when they fail. But on the plus side, it means he keeps his cabinet together for those first years of the war. Lincoln prefers to have them in his own room rather than attacking him from outside. And in his wonderful way, he does manage that.”

Lincoln’s cabinet members “just wanted him to be a better executive”, Hamilton added. “I found these wonderful diary entries … they’re all saying, ‘Why can’t this man just be the commander-in-chief and give orders and stand by them?’ The arc of Lincoln’s story is basically failure, leading ultimately to a point where his opponent overreaches in boxing terms, thinking he’s scored a knockout, and Lincoln gets up off the floor and changes the terms of the war.”

Hamilton was born in England but became an American years ago. From Massachusetts, where he is a fellow at UMass Boston, he will balance publication-week duties – discussions of Lincoln and Davis and their great contest – with watching the aftermath of another momentous presidential battle.

“I’m very worried about the United States,” he said – not just about Trump and the divides he deepens but about what might come next.

“I suppose because I’ve written so much about world war two, about German history and European history, and now the civil war, I think those people who think that there is an inevitable line of progress and democratic improvement and so forth, they’re wrong. And in that sense, you know, that’s what is so moving about Lincoln, is that he sees what’s always at stake. It’s not just money and northern prosperity or whatever. It’s something far greater.”

-

Lincoln vs Davis is out now

.png) 2 months ago

17

2 months ago

17