Luxury tourism in the Caribbean sells a kind of timelessness. A paradise of sun, sea and sand. But to step off the cruise ship or away from the all-inclusive resort is to see a more complex picture: a history of colonialism and a future of climate devastation. New research from the Common Wealth thinktank maps how, over the 400 years since the first English ships arrived in Barbados, empire engineered a system of wealth extraction that shapes the tourism economies of today.

Sir Hilary Beckles, Barbadian historian and chair of the Caricom Reparations Commission, describes Barbados as the birthplace of British slave society. Between 1640 and 1807, Britain transported about 387,000 enslaved west Africans to the island. Extraordinary violence, from whippings to amputations and executions, were a regular feature of their lives. On the Codrington Plantation in the mid-18th century, 43% of the enslaved died within three years of their arrival. Life expectancy at birth for an enslaved person on the island was 29 years old. This was the incalculable human cost of the transatlantic slave economy.

On the back of this suffering was built extraordinary wealth for European colonial powers. Historian Joseph E Inikori has estimated that in the 18th century, 80% of the value of export commodities in the Americas was generated by enslaved Africans’ labour. Although plantation owners in the Caribbean did grow rich – the Drax family, ancestors of former Tory MP Richard Drax, made about £600,000 a year in today’s money from their Barbados plantation in the mid-19th Century – British imperial policy was designed to ensure most of the wealth flew away from the colonies. Two-thirds of the economic value of the sugar industry went to Britain, via the merchants who shipped unrefined sugar across the Atlantic, the businesses such as Lloyd’s of London that insured them, and the sugar refineries that created the final product.

These geographies of production left a lasting mark on the Caribbean, long after the collapse of the sugar industry. Islands such as Barbados now have a “rebranded plantation economy built for leisure instead of sugar”, says Fiona Compton, a St Lucian artist, historian and founder of the Know Your Caribbean platform. She highlights how most of the region’s hotel chains, cruise lines, airlines and booking platforms aren’t owned locally. For every dollar spent in the Caribbean, 80 cents will end up overseas, thanks to large foreign firms repatriating their profits.

Hoteliers were wooed with the prospect of generous tax breaks, while large cruise lines have been able to negotiate extremely low port charges because if a government tries to charge them more, they can just weigh anchor and dock elsewhere.

Segregated inside all-inclusive resorts, tourists often have little interaction with the local economy. On cruise ships, the onboard spas, restaurants and casinos may entice passengers away from even venturing to port. If they do, they typically go ashore through “approved” vendors that have paid to be featured in promotions or, in a growing trend, they set foot on the private beaches and clubs owned or leased by the cruises themselves.

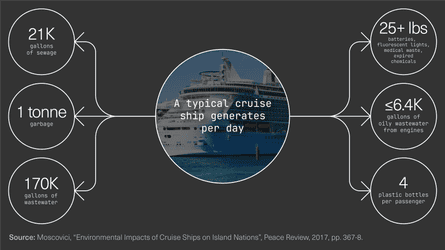

Like the plantations before it, tourism also wreaks havoc on local ecosystems. In one day, a typical cruise ship produces 21,000 gallons of sewage, a tonne of rubbish, 170,000 gallons of wastewater, more than 25 pounds of batteries, fluorescent lights and other chemical and medical waste, and up to 6,400 gallons of oily bilge-water from its engines. Meanwhile, on land, hotels guzzle water and pollute additional supplies, something the water-distressed countries of the region can ill afford, and also consume huge amounts of energy. “Their lights are on all night, they’re burning energy 24/7,” says Rodney Grant, a Barbados government adviser. “Governments alone can’t carry the burden of the social and environmental fallout.”

So why, despite these costs, is tourism so prevalent in the region? “This is the only industry, at least in the current configuration of the global economy, that can generate significant foreign exchange earnings for small Caribbean countries,” notes Matthew Bishop from the University of Sheffield, whose research looks at the political economy of development in the region. In the 1970s and 1980s, some newly independent Caribbean countries experimented with more socialist development models and government ownership of key industries. These were abandoned or violently overthrown under pressure from the US, which even briefly invaded socialist Grenada in 1983. With the only available pathway one of attracting foreign investment to transition away from sugar agriculture, tourism emerged for the Caribbean as the “last resort”.

Although Black resistance – from slave rebellions in the 19th century to worker uprisings in the 20th – forced formal concessions from Britain, catalysing the process for the abolition of slavery and the granting of political independence, the hard truth about the history of empire is that these processes were never accompanied by the kind of transfers of wealth necessary to support real economic freedom. Instead, compensation was paid to slave-owners in 1837 to the tune of 40% of the Treasury’s annual income, while Black workers, especially in smaller islands such as Barbados, were denied access to land that might have freed them from having to keep working in the sugar industry.

Today, across the region, tourism continues to lock local people out of control and access to land. “It’s cultural and economic dispossession continuing in real time,” says Compton. “So many of our childhood spaces where we enjoyed total freedom have been taken over by beach chairs and security guards, who, if they don’t tell you to leave, hover around you to make you feel unwelcome.” She argues that the same land stolen from Indigenous people and systematically kept from Black people during colonisation is now “packaged and sold back to the world as ‘paradise’”.

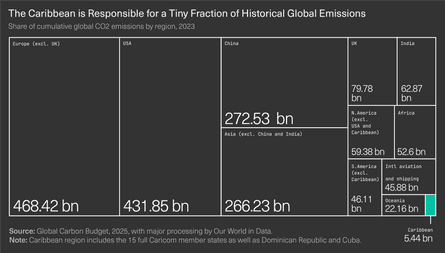

Threatening the “paradise” image is the climate crisis. Despite being responsible for only 0.3% of historic global emissions, the Caribbean is the second most-hazard prone region in the world, suffering floods and increasingly devastating hurricanes such as Melissa. Between 2000 and 2023, climactic events caused more than $200bn worth of damage. This is an existential risk not just for the tourist industry, but the entire fabric of local people’s lives.

“You’ve got this sense that they’re suffering twice,” says Bishop of the countries being battered by extreme weather. “They’re suffering from the original historical injustices of slavery and the period after it, and then they’re also suffering from climactic shocks today. And they’ve received no recompense for either of those two things.” Indeed, rather than money flowing into the region to help with the climate crisis, it flows out to creditors.

Many Caribbean countries are heavily indebted, having borrowed in the 20th century to tackle problems of colonial underdevelopment such as poor public health and education and to build new tourism infrastructure such as airports and harbours deep enough for massive cruise ships. Recent analysis from the Climate and Community Institute found that the region loses roughly the same amount annually in debt service payments as the UN predicts it needs to fund climate adaptation and resilience. Jamaica, which played by the neoliberal rules to reduce its debt-to-GDP ratio from 140% in 2013 to 62%, stockpiling some of its surplus for future disasters, found that the $500m it managed to save could barely touch the sides of the more than $8bn of damage done by Hurricane Melissa.

Rather than continuing to lean on the uncertain and volatile returns of luxury tourism, Caribbean leaders and civil society activists are vocal about the need for reparations. This is about more than mere apologies or token sums of money; real repair would mean a rethink of the entire economic structure that has continued to marginalise the Caribbean.

Compton, for example, wants to see a less extractive model of tourism based around community ownership of hotels, eco-lodges and heritage tour companies. She has created the Caribbean Green Book as a resource for travellers looking for locally owned businesses. Grant also emphasises that Caribbean governments can and should do more. “Tourism doesn’t function in a vacuum, it’s been supported by legislation that we put in place,” he says. He wants to see policy changes to encourage companies to pay more tax and buy food and other goods locally. But while individual travellers can certainly try to make more ethical choices, and Caribbean governments can nudge tourism in a more sustainable direction, deeper structural changes around debt and compensation for climate loss and damages, and funding for adaptation such as new flood defences will require more organised political efforts.

However much luxury resorts try to scrub clean the Caribbean’s past, raking the white sand beaches clean every morning of the sargassum seaweed that blooms more than ever thanks to warming oceans, we all live in a world forged by empire. The question for all of us is – how do we remake it?

.png) 2 months ago

63

2 months ago

63